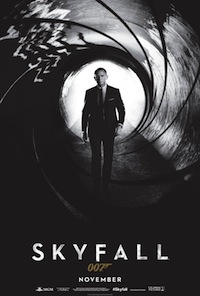

It kind of makes sense that I’m writing about Skyfall, the latest installment in the James Bond franchise, long after it left first-run screens. It actually reflects the nature of the film itself that I’m writing about something that has already been replaced with “the next new thing” at the multiplex. On many levels, Skyfall is about questioning the viability of James Bond in a world on the brink of global economic collapse. It is about reinventing the character who may be on his way to early retirement because he has become irrelevant. In the movie, Bond undergoes a literal resurrection, when he is “killed” and then returns from the dead. But, the movie also kills the traditional James Bond by showing him to be a washed-up tired relic. The interesting thing is that by dismantling him and reinventing him for a new economic era, Skyfall breathes new life into Bond even as it’s beating him down.

In today’s economy, when everyone’s professional stability seems on the brink of implosion, the savvy, suave, trigger-happy professional killer playboy seems a bit outdated and out of touch. Skyfall destabilizes the traditional Bond role of virile infallible alpha masculinity, and shows us a Bond who is as vulnerable as anyone else. Daniel Craig’s Bond starts in a tidy suit, but ends in tatters. He’s more than a little rough around the edges. Worn out and washed-up — literally, twice in the movie — this Bond is less about being an implausible dashing gun-for-hire as it is about being a man who is wedded to, beaten down by, yet inextricably defined by his job. Bond’s hold on his job, his identity and his life are tenuous and threadbare as the economic times from which he has risen. This is a man who mirrors the instability of the world we live in today rather than mimic the glamorous Bond fantasies of yesterday.

Sean Connery set the standard for James Bond when he hit the screen in 1962 with his insatiable appetite for women, fast cars, cocktails and high tech gizmos. But Connery’s Bond was a different character for a different era. Connery’s Bond came from a time where pure escapism still had room to exist. He was a Bond born of the Cocktail Generation that lived and breathed economic denial. Connery’s Bond was brought to life during the advent of globalization. It was a world where Commies were the bad guys, and Capitalism was Savior of all mankind. Bond burst onto the screen at a time when the illusion of infinite economic prosperity seemed possible. We were sending astronauts into space and the world could watch on satellite television. The Cocktail Generation was living high, confident that Western Civilization was conquering the earth and the universe.

Fifty years later, the illusion of global economic prosperity has burst into flames, not unlike both Bond’s workplace and birthplace in Skyfall. There are no illusions of prosperity in this climate where people are losing their jobs, their homes, their medical benefits, and even their televisions. The threat of economic collapse is a reality for the great majority of people who are barely scraping by waiting for their jobs to be eliminated or outsourced at any moment. We live in a climate where people are expendable and are replaced by machines or by cheaper people who are treated like machines. In this context, it would be very hard to embrace the Bond model of playboy killer living the life of excessive luxury.

So the Bond franchise has done what most businesses do. It has created a new model to meet its market, and that is where Daniel Craig’s older, less glamorous Bond comes into play in Skyfall. The character has been transformed into a guy doing his job for the ineffectual bureaucracy he works for. He’s a company man, but the company only cares about itself, while giving Bond the illusion that it cares about him. Both his job and the system that employs him are on the brink of collapse, yet Bond keeps doggedly holding on, doing his job, and slugging away even as he’s beaten down. And that’s what the 007 movies have been forced to do, in a sense. They are a franchise after all, a vastly profitable economic concern. The actors playing Bond only hold onto the role as long as their performance meets the needs of the business. Once they become outdated, they are replaced with newer, more relevant models.

As the movie opens up and we get to know the characters — his boss M (Judi Dench); the diabolical villain Silva (Javier Bardem); the seductress and “fallen” woman Severine (Bérénice Marlohe); M’s eventual replacement Mallory (Ralph Fiennes), and Bond’s co-worker who both shoots and shaves him, Eve (Naomie Harris) —, they all have one thing in common: they are portrayed in relation to work, their employers and/or the tenuous hold they have on their employment. M is being forced into retirement for failing to do her job. The villain Silva is a disgruntled employee. Mallory acts like your standard power-grubbing middle manager. Eve Moneypenny shoots Bond at the order of M and then is demoted to a “desk job” because she’s not “cut out for field work.” The Bond Girl Severine is a prostitute whose existence is bound to her employer. Even the old caretaker Kincade (Albert Finney) is an obsolete worker with nothing to care for anymore but a big empty house. This is not the fantasy world where work looks fun, exciting and prosperous. In Skyfall, work is work.

Like most 007 films, Skyfall begins in medias res with an elaborate, high-action set piece. But this time, it reveals him to be less than a free agent. In effect, this opening sequence shows the collision of the old and new Bond worlds, the one where Bond plays the role of cool, infallible killer and the one where the agency and his role in it seem antiquated. The movie opens with 007 in the middle of a showdown in which his fellow agent is shot by a  villain. Bond attempts to tend to the agent, but his boss M (Judie Dench) orders him to leave the agent and move on. She tells Bond to get on with his job and that he wasn’t hired to save his fellow agent but to track down the bad guy who has stolen an important hard drive. In other words, a hard drive is more important than the employee, suggesting that Bond himself has become regular worker, always at risk of losing his job or, in the case of his high-risk profession, his life.

villain. Bond attempts to tend to the agent, but his boss M (Judie Dench) orders him to leave the agent and move on. She tells Bond to get on with his job and that he wasn’t hired to save his fellow agent but to track down the bad guy who has stolen an important hard drive. In other words, a hard drive is more important than the employee, suggesting that Bond himself has become regular worker, always at risk of losing his job or, in the case of his high-risk profession, his life.

In Skyfall nearly every character we meet proves to be expendable. Bond is no different. But by depicting him as tired and outdated, Skyfall actually finds a way to give his character new life. In the chase scene that follows the opening scene, Bond hunts down the hard drive thief. He starts on a motorcycle in a classic Bond action sequence in which he rides at high speeds across the rooftops of Istanbul. He eventually dumps the motorcycle and runs on foot with no high-tech gizmos, helicopters or race cars to assist him. All he has is his connection to his boss M, who orchestrates his every move. He pursues the thief running across the tops of a passing train. Bond does stop to momentarily check the cufflinks on his impeccable suit, but despite his tidy manicure, he is still a very physical Bond. In fact, on closer inspection, I noted that the suit is impeccable, but Bond is not. The suit actually seems outdated and a tad bit too small, like it was purposely “downsized” so Bond doesn’t quite fit in it. Bond’s haggard body seems at odds with the suit that is squeezing him a little too tight, just as the role within the agency he works for doesn’t quite fit anymore.

Eventually, Bond takes charge of a Caterpillar being hauled on the train, and he wields the backhoe to drag the thief toward him. This piece of machinery was not designed in a secret basement underneath London. It’s the kind of equipment the working class operates, and Bond puts it to use. But it doesn’t matter how adept he is at operating heavy equipment or how well-placed his cufflinks are. Bond is still expendable. When his boss M realizes that Bond’s colleague Miss Moneypenny has a shot at the thief even at the risk of killing Bond, M orders her to “Take the bloody shot.” Bond is shot under the order of his boss, and the tale that follows puts the idea of the expendable employee at the heart of this story.

The movie cuts from this opening chase scene and the shooting of James Bond by his employer to a classic 007 opening credit sequence. We see iterations of Bond – the man with the gun and the suit –inside the signature Bond Eye. Images of death and resurrection beautifully blend into a richly colored textural montage of the lives and deaths of Bond. An image of Bond with a bullet shot through him repeats over and over. Adele sings the theme song (which she also co-wrote) and repeats the refrain “This is the end.” But the end of what? Is it the end of Bond? After all, we last saw him gunned down from the top of a train. Then again, it can’t be the end that early in the movie.

In a way, Skyfall is the end of Bond. The movie shows his workplace being blown to bits after the opening sequence and ends with his point of origin in flames. But by making Skyfall the end of Bond, the film actually crafts a new beginning. This is the end of the old James Bond. The new Bond is a worn-out workhorse who refuses to go to pasture. He slugs away for the agency because it’s the only life he knows. Sure there are some beautifully filmed action sequences, but this Bond is not glamorized with a lot of high-cost high-tech gizmos to get the job done. He has his body. He has his gun. He gets the job done.

In that first chase scene, Bond is not killed by the gunshot, but he chooses to play dead for a while. However, when MI6 is blown up by the bad guy, Bond’s “loyalty to country and to his job” inspire him to drag his drunken, tired, and battered body back to work. He shows up at M’s doorstep, and when she asks him why he didn’t stay dead, the answer is written in the resignation on his face. He knows he is defined by his job as 007. Without it he is no one. It turns out that the hard drive that M is after contains the identities of all MI6 agents, and the villain who stole it wants to expose them on the internet, which basically is a death sentence for the agents. So the very crime that is committed is a tactical maneuver to make all M16 agent workers obsolete by exposing them and killing them.

The villain is the wonderfully diabolical Silva (Javier Bardem) who is really pissed off at M and the agency she oversees. Silva has a major chip on his shoulder and a grudge against the system that employed him and then disposed of him. While he was preened by M to be a Lead Agent, when M realized that she could sell him out to save six agents, she had no problem making him resort to eating cyanide. It’s all in the numbers. She traded one agent for six. It’s what was best for business.

Silva’s headquarters are set on Hashima Island which was established by Mitsubishi as a coal mining enterprise in 1887. The setting is no accident. The blocks and blocks of concrete apartments that we see in Skyfall were occupied by Japanese workers who were abruptly put out of jobs in 1974, when coal was replaced by petroleum. Now it is occupied by the ghosts of unemployed, obsolete workers. The island is the physical embodiment of Silva’s position with M, of Bond’s tenuous hold on his job, and of the Bond franchise itself which has to keep replacing old models with new models in order to maintain stability in the market.

The psychology of work is at the heart of every character in the film, and Silva pulls it all together in his villain role. He mocks Bond for his foolishness of buying into a system that could give a rat’s ass about him. In fact, Silva uses the allegory of rats turning into cannibals to describe what happens when workers are thrown into a sealed container only to become trained to feed on each other until the “last rat is standing.” It’s the rat-eat-rat world of the global marketplace where people are forced to eat their own to survive. This allegory breaks yet another illusion of Bond’s character. In the past, Bond may have seemed like a free agent because of his luxury lifestyle, but in Skyfall he’s clearly in bondage, owned, controlled and disposed of by the state system for which he works. When he faces the villain Silva, he is forced to confront his own fate as another expendable bureaucratic functionary.

Silva is clearly “sexually suspect ” (e.g. “queered”), and the one overtly homoerotic scene between he and Bond further destabilizes the Bond ideal of the infallible and unbeatable Alpha Male. When Silva runs his hand over Bond’s bare chest and talks about how it’s James Bond’s “first time,” Bond fires back at Silva, “How do you know it’s my first time?” It’s a clever retort, but also one that washes his infallible heterosexual virility down the drain.

The homoerotic undercurrent isn’t limited to this physically specific scene, either. Silva and Bond also share a very unhealthy and ultimately self-destructive relationship to their employer M, who they have treated as a substitute mother. M, a ruthless business woman, uses Silva and Bond’s vulnerability to benefit MI6 and the state for which she works. Silva literally refers to M as “Mommy” and cites her extensive catalog of lies and betrayals to Bond. She is the Bad Mommy who has reared two very dysfunctional children – Bond and Silva. M’s every action is motivated by what’s best for the organization. She fosters the illusion of caring for her worker agents because it’s strategic, not because she actually cares. When Silva confronts her with his mangled and deformed face that is a result of M’s decision to sell him out, M replies that “Regret is unprofessional.” Not a lot of nurturing in that statement!

In an early scene, after Silva blows up MI6 headquarters, M stands in a government building filled with the coffins of dead agents, casualties of the workplace. Sure there is a trace of grief on her face, but really it’s more regret for her own professional fuck-ups that impact her than for the dead agents. This scene is emblematic of the coffins M is responsible for through her “professional” decisions, for the dying ruins of the system she works for, and for her own imminent obsolescence.

M refers to her workers as “coming from the shadows.” They’re better that way because they are invisible, and invisible labor is always most beneficial to the system that profits from it. Give them a number (such as 007) and send them to work. M orchestrates her employees’ actions within the insulated safety of her government office, giving orders as if the agents are her puppets. When she accompanies Bond to his childhood home Skyfall and Bond reflects on his dead parents, M states with cold practicality, “Orphans always make the best recruits.” Sure they do. Then they can be adopted by their employer and become inextricably beholden to the system for which they work.

Given how wretchedly M treats Bond — she orders an agent to fire the bullet that almost kills him, turns her back on him when he “returns to work,” sends him back into the field because it benefits her even though she knows it’s putting him at risk — he still clings to her skirts and actually cries when she is put out to pasture. Why does Bond cry for M? Why does he report back to duty after she nearly killed him for the benefit of MI6? Because being 007 is the only identity James Bond has. 007 is not just his job; it’s his life. Without his job, he’s no one. Bond doesn’t want to be relegated to the rest of the jobless no ones, so he hangs onto his job even as it beats him up and attempts to dispose of him. In fact, Silva blowing up the workplace is what brings Bond back from the “dead.” He resurrects himself to save his workplace, not to save himself.

When Bond is training for his return to work in the field, there are no traces of the suave agent in the tidy suit. He wears baggy sweatpants and looks old, ragged, and out of shape. In target practice, the shots he takes are as messy as he is emotionally and physically. This is not the sharp-shooting playboy assassin. When he is given his tools for his next mission in the field, there are no fancy gizmos, no high tech machines. He’s given a hand gun and a “standard issue radio transmitter” to use as a distress signal. The box they come in has a lock, but Bond isn’t even given the key. It’s just an unlocked box with a gun and a radio.

Indeed there is very little high-tech spectacle in Skyfall. This is a gadget-free Bond, who uses his handgun and his body to get the job done. When he is given his gun and radio, he is sitting in a museum looking at a Joseph Mallord William Turner painting of an old retired ship. Bond himself is an old worker on the brink of being sent out to pasture, just like the ship in the painting. He looks at the ship and says that he’s “Going back in time, somewhere where we’ll have the advantage.” And that is exactly what happens. Bond goes back in time to his point of origins. He goes back in time before The Age of Prosperity spawned a Bond tricked out with high tech weapons and gadgetry. This Bond ends up using old techniques to teach “an old dog new tricks.” In other words, he makes something new out of the old. He ultimately defeats the bad guy by using hardware in a software world.

Computers become useless and don’t solve anything. They only cause more problems. When it comes down to the showdown, shotguns and homemade bombs assembled from broken light bulbs and nails get the job done. It’s no surprise that Bond, M, and the old caretaker Kincade join together for the final showdown. They are three old workhorses who join forces against the enemy. When Bond completely blows up his point of origin, he does it by stringing a couple of sticks of dynamite to some propane tanks, standard fare that doesn’t require any kind of exclusive privileges to high-tech, top-secret weapons manufacturing.

There are also very few cars in the movie. He starts the movie on a motorcycle, but then he tosses that aside and is nearly always physically on the run. He eventually unveils the old classic James Bond Aston Martin (much to the audience’s delight), and it’s like he’s uncovering a fossil. It’s like an old dusty relic with its red eject button and its guns mounted to the front fender. But it’s an effective relic. Bond drives the car back to his childhood home – Skyfall – and in so doing goes back to his primal origins: a man with a gun and a car. He uses the old Aston Martin as a weapon, but then he blows it up with the house, blowing up his origins, both as the character in this specific movie and as part of the 007 franchise.

Threads of the old James Bond do still exist in this movie. There is a Bond Girl, Severine, who is Silva’s concubine and slave. Bond develops an attraction to this seductress who wears a gun strapped to her thigh. In fact, he gets a bug up his arse to save her, most likely because he strongly identifies with her once he realizes that they are both prostitutes in their own way. In one fairly absurd scene, Bond gets naked in the shower with Severine. This undoubtedly is an attempt to resurrect Bond’s image of virility, but the scene just ends up making him look vulnerable and exposed. He arrives on her boat, not knowing who is there or what he’s in for, and he takes all his clothes off and climbs in the shower? Seems pretty stupid.

When Bond’s poor marksmanship leads Silva to take the gun into his own hands and send Severine to her untimely end with a shot glass of scotch falling off her limp head, Bond replies, “A waste of good scotch.” Again, this is an attempt to resurrect the ruthless Bond of old. But the words are spoken with so much resignation they become more of an excuse for Bond to contain his emotions and guilt. Another expendable employee bites the dust, and Bond facilitates her demise

Though Skyfall expends a lot of energy freeing the Bond franchise from the burden of the past, it is still a James Bond film and has enough flash to please the audience rather than just beating us over the head with the Bond-As-Washed-Up-Workhorse motif. The cinematography does not fall short, from the high-speed chase in Istanbul to a “hand-built” set in Shanghai that dazzles the eyes with shimmering high rises with giant jellyfish projected on their surfaces. The Shanghai scenes have enough eye candy to fill any Bond appetite. The slick high-artifice of the set reflects the New Global Economic World which the new Bond inhabits. His image is reflected on the surface of the buildings as he grabs onto the bottom of an elevator and scales the buildings by holding onto the rising machine with his bare hands. Likewise, when Bond enters the casino in Macau through the mouth of a dragon, he is surrounded by glowing lanterns and a glamorous world of high-risk gamblers and menacing bad guys from the underworld. Certainly Sean Connery would be right at home in both these scenes.

But as soon as Bond moves to Hashima Island, then to the London Underground and finally his childhood home on the moors of Scotland, the glitz is subverted by crumbling history. The concrete apartments, abandoned bicycles and fallen statues of the island show us a world that has been crushed by economics. The Underground is still functional, obviously, but clearly dates from another era. And Bond’s ancestral home Skyfall stands as a gutted totem from the past. It’s a house from a different time and different world far removed from the shiny veneer of Shanghai and the global economy it represents. Everything at Skyfall has been sold off to auction. The empty halls of Bond’s childhood home are completely lacking in ornament and technology.

The showdown at Skyfall is pushed so far back in time that it’s almost like we’re watching a different movie. It plays more like a war movie than a Bond action movie. The dirty, grubby and muddy Bond teams up with his obsolete boss M and the lone caretaker Kincade for a shootout at the moors that could be from a WWII movie. Homemade bombs and a good old fashioned knife save the day. As Kincade says, “Sometimes the old ways work best.” And there’s nothing quite like a good old fashioned knife in the back to get the job done. To hell with computers and high tech weapons and the economy they represent!

After being mostly de-Bonded, killed, resurrected, and put through hell, betrayal and back to hell again, Bond wins out in the end and remains “the last rat standing,” though his prize is fairly mundane. In the final scene he stands atop a government building in London with the British flag waving at his side. Bond is part of the architecture of the state and of his employer. The movie ends with Bond “reporting to work” for his new boss Mallory (Ralph Finnes). Mallory stands with his arm in a sling where he’d been shot. His physical injury is representative of the broken system itself. The “new blood” is already old, yet the system keeps limping along as 007 picks up a folder containing his new assignment, and the James Bond theme song clicks into action. Can’t kill off a successful franchise quite yet.

The movie ends with another day and another job for 007. This all sounds terribly depressing. What is the appeal of a James Bond movie that completely destabilizes the Bond image of indestructible virility? A movie that turns him into an increasingly obsolete worker employed by a crippled system? Does the old Aston Martin hold it together? Is the slick suit that the film wears on its surface just snug enough to hold the Bond package together? Or is it that in this day and age, the image of an old dog who won’t die is more attractive than the debonair playboy? After all, there is enough Bond left to save 007 so that he comes out as “the last rat standing.” Perhaps that’s the best we can hope for in this rat-eat-rat world.

Kim Nicolini is an artist, poet and cultural critic living in Tucson, Arizona. Her writing has appeared in Bad Subjects, Punk Planet, Souciant, La Furia Umana, and The Berkeley Poetry Review. She recently published her first book, Mapping the Inside Out, in conjunction with a solo gallery show by the same name. She can be reached at knicolini@gmail.com.