My old friend Robert Hoyt — singer/songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, organizer, nurse, father, lover of the wild — died on the morning of February 1st, 2023, at the age of 68, only weeks after being diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer. He hadn’t wanted to make his illness public, and only a very few of his friends and relatives were aware of it. I’ve been getting beautiful personal messages from many people I haven’t seen much or at all since the 1990’s with updates.

Just to say from the outset, I will not be writing the definitive remembrance of Robert, and I’m not sure if anyone else could do that if they wanted to try to, either. It may be a stretch to say that Robert led many lives, but he certainly embraced a number of different identities over his lifetime, certainly on a musical level at least. I suspect any thorough effort to pay homage to the man would have to involve at least four or five different people, who knew him during different stages of his life.

The Robert I knew best was probably the one known by the widest array of people, throughout the 1990’s, when he was a traveling troubadour who identified strongly under the banner of Earth First!.

Robert was born and raised in Macon, Georgia, along with two brothers (if he had other siblings I hope they will forgive me, I’m going on memory here). I was introduced to Robert by another singer/songwriter from the state of Georgia, Chris Chandler, who whisked me up off the streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts one cold winter day to take me to upstate New York, where the People’s Music Network was having one of their biannual gatherings. If memory serves, this would have been January 1991.

Robert had come to the PMN gathering mainly because Chandler recommended it, and it was a long way to drive from Decatur, the hip neighborhood in the Atlanta metro area where he was living then, and where he maintained a PO Box long after he no longer had a residence there.

I don’t think Robert ever came back to a PMN gathering after that one. For me, this gathering was the first of many, and the beginning of a long-term friendship with Robert, along with other folks I met there that winter.

Robert had recently recorded an album called As American As You. Like Dumpster Diving Across America and Mind’s Eye, which he put out over the following decade, it was full of hard-hitting and often truly eloquent, driving songs featuring Robert expertly playing guitar, bass, keyboards, and singing brilliant harmonies with himself, mostly on subjects related to environmental activism, and critiquing various aspects of modern industrial high-tech society, in favor of the ecosystems, the trees, the animals, the wild, with a smattering of songs on more acceptable subjects — but no less heartfelt ones for Robert — such as loneliness and lost love.

In the early 90’s I was moving around a lot, but whether I was living in Massachusetts, Connecticut, San Francisco or Seattle, Robert would be touring there, and coming to visit. We’d swap songs and talk about what we’d each been up to, which for me meant hearing lots of great stories from Robert’s work. Robert’s work throughout the 90’s mainly involved touring around the US and playing shows on college campuses, sponsored by environmental activist groups on each campus, often affiliated with the Student Environmental Action Coalition, and spending his “free time” during the summers on the front lines of eco-defense, blocking logging roads and supporting tree-sits such as the Cove-Mallard campaign in Idaho, about which he wrote a great song called Jack Road.

At some point in our regular encounters he would mention the idea of me traveling with him, playing bass guitar and singing harmonies. I was always too busy with whatever I thought was more important than traveling with Robert, until I finally took him up on the idea, which was either in the spring of 1996 or 1997 (maybe someone out there remembers which).

Fans of Robert’s album, As American As You, will be aware that Robert’s father worked on a military base, claiming to be a fixer of clocks. As Robert grew up he realized that this was just a story, and to my knowledge he never learned what his father actually did for a living.

His dad had died sometime before I met Robert, but his mother was very much still around. Our time together that spring began with a week or so at Robert’s mother’s home in Macon, being looked after wonderfully by her as we rehearsed the set lists until I got his bass parts and harmonies down cold. Then we hit the road. What followed was an absolutely amazing education, on so many fronts.

Traveling on my own or with other young friends was always memorable, but traveling with someone like Robert, who knew people everywhere and sang for them, was a whole new thing. I had traveled as a bass player with other artists before, but never had I met so many kindred spirits in the space of a few months. In that spring of traveling together I met people who I’d see again on many occasions, who became long-term friends and comrades, in too many places to list, from Vermont to Tennessee to Indiana to Wisconsin and so many other places.

It was during these long hours of driving day after day, week after week, month after month, when we got into a whole lot of both talking about life on planet Earth as well as recounting stories from our pasts. A few months may not seem like a long time, but when you’re spending several hours each day during that time alone in a car with one other person, it can be intense, in various ways, but with Robert, overwhelmingly in positive ways.

I won’t paper over the negative ones though. The biggest of them being Robert’s cat, Claude.

Just before I started writing this missive, I discovered that the documentary from back around then, Travels With Claude, has just been put up on YouTube by the filmmaker, Paul Bonesteel. I’ve been watching it again today, for the first time in decades — it’s a wonderful document of history, and tribute to Robert, his music, and his organizing.

For those who haven’t seen the movie, Claude was a paraplegic tabby cat. Paralyzed from the waist down by a tragic accident involving an ex-girlfriend of Robert’s and a closing door, Claude came out of it decidedly worse for wear. Many pet owners would euthanize a cat in such a situation, but Robert nurtured the orange cat and learned from veterinarians how to position Claude and squeeze his bladder the right way, which made his tail flip up into the air and caused him to squirt pee in whatever direction Robert was aiming him.

Helping Claude pee every eight hours or so was necessary for keeping the cat alive and prosperous. For Robert, this meant that throughout the 1990’s, he could never fly anywhere without leaving Claude with a veterinarian capable of looking after him, at great expense. So although he was in demand for gigs all over the country, he did all his touring by land, in a pickup truck.

Normally Claude’s home was the passenger seat of Robert’s pickup truck. Robert went through a couple pickup trucks during the 90’s, but he always traveled in and largely lived out of a pickup truck with a cab on the back (just as I soon began to do, for many years). During the season I toured with him, Claude had to be relegated to sitting in the back, which he could freely access with a ramp Robert had put in there. Which also meant that Claude could slide out of the back and into the front anytime he wanted to let me know just what he thought of this guy usurping his seat in the pickup.

This was still before either Robert or I had gotten an email account or websites or any of that sort of thing. We took breaks from driving every day to eat at truck stop buffets, and use the free phones that back then could be found at each booth. We also spent a lot of time at photocopy places, putting address labels and stamps on untold numbers of postcards we’d mail strategically around the country to promote our gigs to Robert’s mailing list. Amid these sorts of activities, as I was writing letters to my girlfriend back in the northeast, I would involuntarily decorate them regularly with blood stains from my latest wound. Claude clearly believed the best defense was a good offense, which makes sense for a paraplegic cat, and his front legs were probably as muscular and powerful as a small mountain lion. He was definitely taking it easy on me, all told.

My memory going back that far is too foggy for me to remember whether I met Anne Feeney through Robert or through Chris Chandler or by some other means, but the late Anne Feeney was a close mutual friend of all of us. When Robert wasn’t around and Anne and I could freely talk about our dear friend behind his back, as you do, Anne’s chief complaint was the same as mine, which was the mild scent of cat piss that might generally be emanating from the back of Robert’s truck. Anne thought that Robert needed a girlfriend, and that in order for him to find one, he’d have to lose Claude one way or another. The very thought would have horrified Robert, so Anne would share her laments about the cat with other people.

Through Robert I became very familiar with the wonderful music of folks like Darryl Cherney, Judi Bari, Danny Dolinger, Dana Lyons, Casey Neill, Peg Millett, and others who made up the cultural backbone of the Earth First! network as it existed then. All of Robert’s concerts were an introduction to these artists, with live renditions of “Who Killed Judi Bari,” “Ghost of a Chance,” “Turn of the Wrench,” and “Dancing On the Ruins” being regularly featured. Robert’s concerts were also always an introduction to whatever was happening with Earth First!-related activities, forest defense campaigns, conferences, and other things that were ongoing or coming up somewhere. In the 80’s and 90’s there was a fairly popular concept, in certain circles, of the “road show,” or specifically the concept of the Earth First! Road Show, which varied widely, but generally involved at least one speaker and at least one musician, doing popular education about the situation with the forests, and recruiting for ongoing forest defense campaigns.

Anne Feeney was not the only person who thought Robert needed a girlfriend back in the 90’s — Robert tended to agree. But most of the time, instead of spending much time hanging out with people like gig organizers and their friends offering to put us up in a nice house with beds and hot running water, unless the gig organizers in question lived deep in the countryside and off the grid, Robert’s plan was generally to turn down these offers in favor of driving an hour or two to an ostensibly nearby patch of national forest land somewhere, and camp. Or technically, he’d sleep in the back of his pickup with Claude and I’d camp.

Robert was fairly profoundly introverted, and seemed more comfortable in the company of one or two old friends than with larger groups of less familiar people. On many nights after gigs I’d be enjoying myself and my surroundings, while at the same time mildly stewing over having to leave a nice party in some college town so we could go camping in some beautiful, remote location, where we’d play music together and talk around a campfire, him drinking cheap wine that he always had in the back of his truck, and me smoking cannabis that I also always had somewhere accessible. Good times in the woods aside, abandoning most of the parties wasn’t a good dating strategy.

Eventually, fleetingly, I learned of the lives Robert had lived before he became an Earth First! troubadour. In the 70’s he played in different bands, but he never played me any of the music they might have recorded, or told me the names of the bands, or the names of any of the hundreds of songs he apparently wrote before he recorded As American As You. He referred to the decade prior to the AIDS crisis as the “Sleazy Seventies,” because of the amount of gratuitous sex that he thought was going on all over the place, with some concert attendees specializing in developing relationships with different band members, depending on which instrument they played. He never seemed to miss the 70’s, on the rare occasions the subject came up.

In the 80’s, by his own recounting, he might have qualified as a yuppie, working a good-paying IT job (as it would be known in today’s jargon), and eating a lot of sushi. Then he quit what he called the high-tech plantation and began to write songs encouraging other people to do the same (such as “Quitting Time” from his 1995 album, Dumpster Diving Across America).

For a few years after our time traveling together, I continued to see Robert often. We were both touring in largely the same circles, and our paths often intersected. One memorable evening during this span was September 10th, 2001, when we both sang at a conference related to the global justice movement, organized in part by Allie Rosenblatt, who had recently been a student organizer, and was still an organizer, there in Indiana, where Robert was now based. The next morning, Robert uncharacteristically woke everyone up to make us listen to the radio, which was reporting that planes had crashed into the Twin Towers.

By this time Robert had found a wonderful woman, an extraordinary organizer named Karyn Moskowitz, who could put up with Robert’s cat, and they had a daughter together, named Cicada (now a brilliant young woman of 23). I guess Cicada would have been about 2 years old at the time of one of the last gigs Robert and I had together that September in Bloomington. She wandered onto the stage during our show, holding her arms up so her daddy would pick her up, thus completely destroying the depressing atmosphere around the beautiful song Robert was trying to do at the time, about a mass lynching that took place in Ocilla, Georgia, in which hundreds of local residents threw a piece of wood on the fire that was burning a man alive.

The frequency with which I saw Robert, Karyn, and Cicada in the two decades since then decreased drastically as the 21st century progressed. The last time I saw any of these good folks was six years ago, by my recollection, which was the last time I was in either Indiana or Kentucky, where Robert and Karyn ultimately had separate homes, Robert in the middle of nowhere next to the Hoosier National Forest, Karyn in a town where the humans probably outnumber the squirrels.

Robert got a nursing degree sometime along the way, and worked as a nurse, taking care of people and having a stable income. I’ll bet he had a positive impact on a lot of people’s lives, be they patients or coworkers. I’d love to hear some reflections from folks, but I know nothing about all that.

Six years ago when I and a friend visited and stayed with Robert at a place where he was living outside of Bloomington, closer to where he worked, he gave my friend and I a wonderful private concert in his living room. He was working on an entirely new act that he was calling Bob Palindrome, for which he had written an entirely new body of material, the vast majority of which were songs about lost love, some of which, depressing as they are, could have been hits in Nashville, if they were being performed by a different artist with connections, and those kinds of ambitions. He had worked out his new material entirely on a keyboard, the main instrument he played in the 70’s, which he played flawlessly, just like he played the guitar, just like he sang melodies or harmonies.

He was wanting to keep his Bob Palindrome identity separate from his identity as an Earth First! troubadour, but now there’s no damage that can be done by spilling the beans (I hope all of Robert’s other friends, fans and family agree with me on that judgement call). He asked me for advice on promoting his new act online — a subject I know something about, generally, but I know a lot more about promoting Robert Hoyt than Bob Palindrome, and I don’t think my suggestions were helpful.

I regret that that visit six years ago was the last time I spoke with Robert. I don’t know how the time slipped away like that over the past twenty years or so, but it did.

I don’t really know if Robert moved on from being a constantly-touring performer mainly because he wanted to spend more time with his partner and kid, or because he thought it would be more responsible and grown-up if he got a real job, or because it had become impossible to tour and perform without being very actively online and engaged with the high-tech plantation in a big way, or because what had for so long been his bread and butter, college gigs that paid well, were all drying up and disappearing, as a common phenomenon. Or perhaps all of the above.

Robert talked back, I don’t know, twenty years or so ago about how when he stopped trying to get gigs with student environmental groups and such, he also stopped hearing from them. He seemed disillusioned to discover that if he didn’t call them, they weren’t calling him. I’m not even sure to what extent he was aware that a big part of the reason why he wasn’t hearing from them might have been because they no longer existed.

One of the folks who let me know that Robert was on his deathbed was Danny Dolinger. Danny and Robert, and I think all the other musicians I mentioned earlier, have long played regularly at annual events put on by an environmental activist network in the midwest called Heartwood. It’s been a long time since I’ve been among them, but I was happy to hear from Danny that they’re still going on, and that only a few months ago at one of these gatherings, Danny and Robert were singing all of their great songs of community and resistance together around a campfire.

One of the most moving songs Robert wrote, that I especially enjoyed singing with him, was “This Star.” He wrote it for Peg Millett, while she was in prison for Earth Liberation Front-related efforts. It was the perfect song to connect a beautiful, starry night in the forest with a political prisoner in a concrete box somewhere, who might get to see the night sky every now and then if they’re lucky.

And when you see this star think about me

About the times we had and times yet to be

Look for the star and know when you do

That I’ll be watching this star and thinking of you

Whether it was intentional on Robert’s part or not, the only Robert Hoyt album that you can find on some streaming platforms (like YouTube) is Mind’s Eye, a fantastic album. Whether As American As You and Dumpster Diving Across America aren’t there because he never got around to uploading them or because these albums no longer met his standards, I don’t know, but I wouldn’t be surprised by either possibility. Either way, Robert was not a fan of technology or the internet, and engaged with things like websites, music streaming, or social media platforms on a sporadic and very limited basis, which I’m fairly sure is the main reason you’ll find so little about him online.

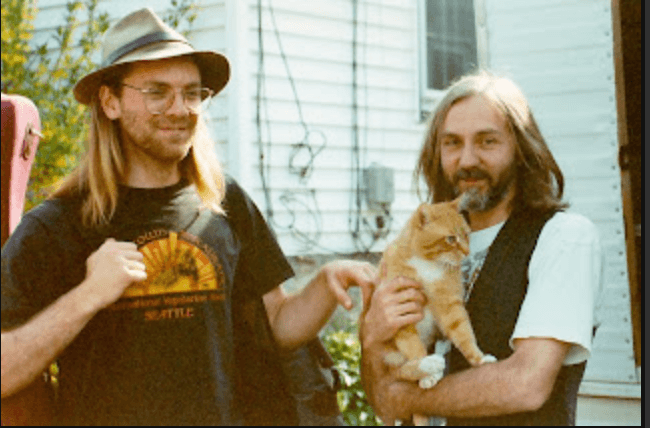

You won’t find Robert Hoyt on Spotify, but you will find Bob Palindrome. The guy in the hat there, that’s Robert, a man who made a big difference in the world for a lot of people, very much including me. One of the best things I ever did in life was to be Robert’s bass player, no doubt about it.

Long live planet Earth, and long live Robert Hoyt. I’ll see you at the campfire, beneath the stars, guitar in hand.