As a geographer who has studied and taught about interethnic conflict around the world, and as a U.S. citizen with family roots in East-Central Europe, I’ve always read the stories told in the maps.

These two maps show how Putin got it wrong, and miscalculated in launching his war against Ukraine. Putin claims that two of his war aims are the “denazification” of Ukraine, and the protection of the Russian-speaking population from far-right Ukrainian ultranationalists.

Like most “Big Lies,” there is a kernel of truth behind the claims. After the 2014 Maidan revolution, I raised alarms about fascist influence in the Ukraine’s new government, asserting that “the enemy of your enemy is not always your friend.”

I was alarmed that far-right Ukrainian ultranationalist groups (such as Svoboda and Pravy Sektor), who feel that the wrong side won World War II, provided revolutionary street fighters who sported “white power” symbols. Their followers reversed bilingualism, built many monuments to fascist war criminals, and joined the National Guard’s Azov Battalion to fight Russian ultranationalist separatists.

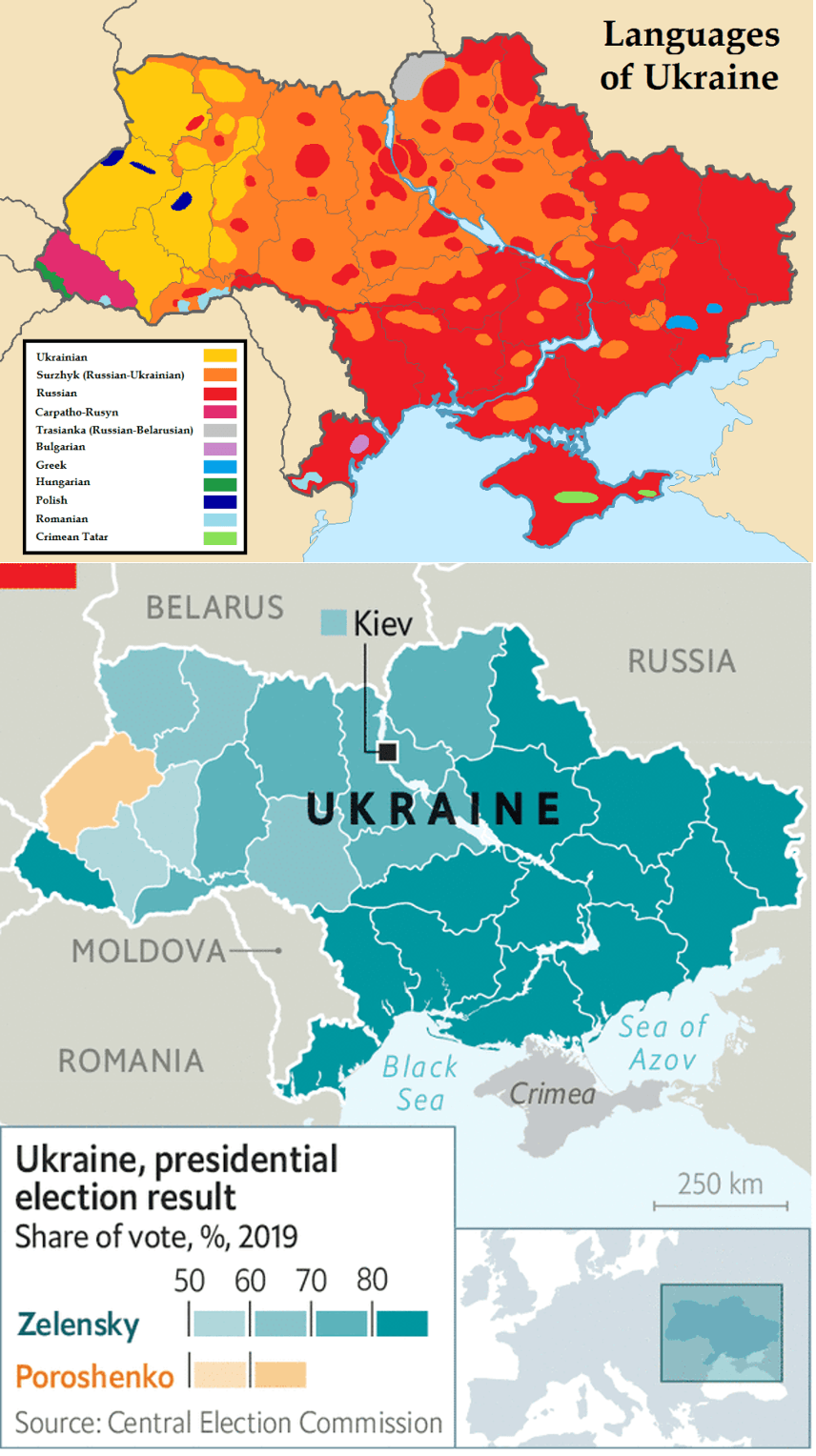

Putin portrayed Ukrainian fascists as a threat to the Russian-speaking population in the east and south (shown in red on the first map), and he annexed Crimea and armed Russian separatists in the far-east Donbass region. Ukrainian nationalists are strongest in the far-west Ukrainian-speaking region around Lviv (shown in yellow), which was part of interwar Poland. Many Ukrainians in the central region speak a mixture of Ukrainian and Russian (shown in orange).

In Ukraine’s past presidential elections, the electoral map would almost perfectly match the language map. Pro-Russian politicians would win the red region, Ukrainian nationalists would win the yellow region, and they’d split the difference in the orange region. (The farthest-right parties on both sides would not get as many votes.) When I taught courses on the geography of East-Central Europe, I’d introduce these maps to show the imprint of ethnicity and remnant national borders on modern politics.

But in the 2019 election, something different happened, shown on the bottom map. Fed up with corrupt politicians of both ethnic groups, voters overwhelmingly chose Russian-speaking Jewish candidate Volodymyr Zelensky as president, in a rebuke to both Ukrainian and Russian ultranationalists. Zelensky actually did better in the Russian-speaking region (in dark green), and his opponent only won in the immediate Lviv area (in light orange).

Putin would like to take over Kyiv to topple Zelensky, and replace him with a compliant puppet president of all Ukraine. More likely, he would ultimately want to partition Ukraine, and create an eastern Russian-speaking “Novorossiya” state (in the red area), joining the Donbass to Crimea and the pro-Russian Transnistria enclave in Moldova. That would leave a rump Ukraine in the western and central (yellow and orange) regions.

But here’s the thing: how can Putin convince Russian-speakers to help topple a president who they voted for in larger numbers than Ukrainian-speakers did, over a candidate backed by voters in the most Ukrainian nationalist region? How does that make any sense as a way to fight Nazis? Perhaps because Zelensky doesn’t adequately play the role of bogeyman, Putin has to topple him.

The antiwar protests in Russia are remarkable and unprecedented, but what’s really notable is the lack of support for Putin’s war from Ukraine’s Russian-speakers, whom he’s supposedly “liberating” from the fascist thugs. It’s notable that even Russian state TV can’t engineer a scene of ethnic Russians welcoming the army, which was so easy to show in Crimea only eight years ago.

It’s actually Putin’s invasion that could confirm his self-fulfilling prophecy, by elevating the far-right militias in western Ukraine, and convincing more Ukrainians that they need to join NATO. That might be exactly what Putin wants, because he can continue to use Nazis and NATO to frighten the Russian people into following his will. Just as Russian and Ukrainian ultranationalists reinforce each other’s messages of hate, Putin’s aggressions and NATO expansions feed off of each other’s messages of military might.

This region of Eastern Europe is marked by unresolved historical trauma, including past imperial invasions, Stalin’s Holodomor (Great Famine) of 1932-33 that claimed 3.5 million Ukrainian lives, and Hitler’s war of 1941-45 that claimed at least 25 million lives throughout the Soviet Union. Everyone fears a confrontation between the nuclear-armed powers of Russia and United States, which would be in nobody’s interest, especially Ukraine.

Putin and his oligarchs run a shaky Russian economy, and his first goal is to stay in power. Like many western leaders, he sees the path toward xenophobia and war as the way to control his own people with fear. Yet it seems that now both Russians and Ukrainians are starting to lose their fear, and beginning to think of standing up to empire.