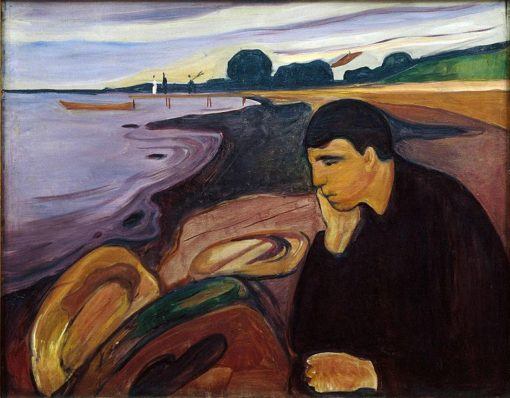

Edvard Munch, Melancholy, 1894-96 – CC BY 2.0

I moved to Dortmund, Germany about three months ago, though it feels more like six or twelve. The hours stretch here in a way I’m not accustomed to, even living, as I used to, in a what my landlord in Iowa City called the “Spinster’s Cottage”—a little shack originally built for an aging and unmarried daughter of the town, inside which I couldn’t fully stretch the length of my wingspan. As I did in Iowa City, I spend much of my time here in Dortmund in my house, but for different reasons—where once I favored seclusion in hopes of writing more and better, and also because of the months of numbing Midwestern cold, here I favor seclusion because I don’t speak German well, and every minute outside bends precariously under a series of small but weighty embarrassments. These are the types of experiences a dean warns her junior year study-abroaders about, under the heading of culture shock, telling them in advance to just take it in stride. At thirty-one, though, I have limited youthful zeal, and limited bandwith, as has become fashionable to say. Presented with retrieving a loaf of something called “fire bread” from the series of plastic tubes at the grocery store, I abandon the task.

Though breadless, I am not an ingrate or sadsack, particularly when I get out of the house, get moving, get on the S-Bahn. Taking the train here in Germany is a perpetual reminder of how inferior any such system is in the United States. For some time in Iowa, I would take the Amtrak from Fort Madison, a town in what someone once termed to me the “teat of Iowa,” to New Mexico, where my family lives. One of the joys of that experience was the dining car, in which the staff, with deliciously impenetrable logic, assemble groups of strangers at the tables. Amtrak, attempting deference to a new, millennial audience (but mostly cost-cutting), is now phasing the dining car out. Millennials, a Washington Post article went on the subject, are “known to be always on the run, glued to their phones and not particularly keen on breaking bread with strangers at a communal table.” I met some unsettling characters at the communal table, true, but I remember, too, an elderly lady with a wicked laugh, and a man I saw two separate times, on two separate train journeys, with whom I was randomly seated both times. He was returning from taking care of a close friend with multiple sclerosis and was a retired train engineer. We stared out of the panoramic window over our steaming baked potatoes and he talked at length of engine repair.

There’s a current in American letters these days, particularly among millennial writers, of writing in a high literary style about solitude, about loneliness. I’ve attempted it, though it’s never amounted to much and I frustrate myself quickly with how little there is to say. The treatment of loneliness in contemporary literature often feels like how it felt to live in the Spinster’s Cottage—a little obvious, boring, and cramped. Which is not to say the subject itself is unworthy. Much has been written about loneliness and solitude, and the relationship between the two, that has not been boring. (“It might be lonelier without the loneliness,” wrote Emily Dickinson, recognizing that the feeling provides its own company, of a kind.) Vivian Gornick, Banana Yoshimoto, Mark Fisher spring to mind. Some of their lonelinesses are more painful. I do not recommend reading Mark Fisher, who took his own life in 2017, if you’re looking for a salve:

We need to abandon the belief in the autonomous individual that has been at the heart, not only of neoliberalism, but of the whole liberal tradition. In a successful attempt to break with social democratic and socialist collectivism, neoliberalism invested massive ideological effort into reflating this conception of the individual, with its supporting dramaturgy of choice and responsibility.

It’s the system that the comedian Nathan Fielder, once dubbed the “Wizard of Loneliness” by a disgruntled private-eye, lampoons queasily in his show Nathan for You. That uneasy show, which sits between fact and fiction, is best watched alone, when you don’t have to gauge if anyone else finds it funny, in a soul-tearing kind of way. An acid spoof on the idea of the entrepreneur, and an occasionally ambiguous indictment of capitalism, Nathan for You features Nathan, a middling business school graduate, “helping” struggling businesses with absurdly intricate schemes—he tries to get around tariffs on smoke alarms by classifying them as instruments, for instance, or finds a competitive niche for a local realtor by re-branding her as ghost-and-spirit-sensitive. Part of the joke is that these schemes are eminently recognizable. And that everyone, at this point, is lonely and desperate enough to think they might work.

Recently, I took a high-speed and highly crowded train to Düsseldorf, with a few new friends, to see the writer Karl Ove Knausgaard’s curated exhibit of Edvard Munch’s paintings. In another time, when loneliness glimmered to me, still, with a tinge of adolescent appeal, I was a huge fan of Knausgaard, would tote one or another of his gargantuan “My Struggle” series around on the subway, Karl Ove’s haggard face staring out at people who probably stared at me and rolled their eyes. Knausgaard wrote six of these books, all gigantic recollections of his entire life, every minute of it, so that, as the admiring Zadie Smith blurbed, “you live his life with him.” I loved those books because they presented internality so very fully—and a sense, which I related to, of holding yourself separate from other people—but more, actually, because of the connection I found within the pages. “That’s the point,” Knausgaard said in an interview, of writing, “to be in a place where you are not aware of yourself,” and that is what I found in his books, which were fully and completely about him, about his interior landscape. It seemed a confirmation that everyone was lonely, which was in its way a consolation. “The struggle,” wrote Joshua Rothman, of Knausgaard’s project, “doesn’t ‘mean’ anything, but it is something: not a tune, but a frequency, uniquely his. Perhaps we each have our own.”

Six interconnected tomes on an obscure Norwegian writer’s internal feelings and memory do not necessarily seem like they would become an international phenomenon, but in an ongoing age of loneliness, as this molasses moment has been called, they became so. Knausgaard made a fortune. I saw him reunite with his adolescent band at a bar in Red Hook, to a packed crowd. The group played an R.E.M. song and sang its lyrics in Swedish, and he drummed furiously in the background, and then he stalked off the stage and into a private patio area, inaccessible, smoking. He headlined literary festivals and some stunning fraction of the entire population of Norway was said to read his work. Whether his sudden fame compounded or canceled his loneliness—which he strove for, he said, finding it necessary for his work—I do not know. I stopped reading Knausgaard after a while, because I began to feel he served his purpose for me—he reminded me what it might look like, as a writer, to take notice of every minute, and what it might look like, even in the depths of loneliness, to lose yourself in writing.

Predating Nathan Fielder or Karl Ove Knausgaard, Edvard Munch could rightly be called another wizard of loneliness—“The Scream,” of course his most famous painting, but the one I became acquainted with first, from reproducing it in my high school art class, was “Melancholy,” in which, like so many other paintings, the figure of Munch looks greenish and hulking, Frankensteinian, and lurks on the side of a landscape in which others frolic brightly in the distance. In Düsseldorf, at the K20 museum, this painting was not on display, nor were most of his more famous works. Instead, Knausgaard, who has now written a comparatively slim book on Munch, which sat in the museum’s gift shop (So Much Longing in So Little Space, a title which aptly describes my four years in the Spinster’s Cottage), had chosen a large and diverse array of paintings. There were rich depictions of trees and tree trunks through the seasons; paintings astounding for their un-Munchian brightness; a wall of full-body portraits, in one room, of people Munch had known, and known well, their spirits expressively conveyed with no small amount of humor, at times, and a lightness. A man and a woman met under the branches of an apple tree dangling baubles of shining fruit. Then, too, there was the expected darkness for which Munch is primarily known—the green-faced man tripping through scenes of others’ drunkery and gaiety, a woman bending vampiric over a formless body, and a revisitation of Munch’s sister’s death by tuberculosis, an event that haunted him for the entirety of his life.

I saw the exhibit three times in total: once with my new friends, another time in a span of ten minutes before the museum closed—just me and the guards—and then on December 26, the rooms so stuffed with overstuffed people it was nearly impossible to see the canvases. Something about this exhibit left me feeling slightly tepid—nothing to do with Munch himself, but maybe more the way individual loneliness sells, these days. At the same time that we are told to stay positive, as Barbara Ehrenreich has written extensively on, about the state of a rapidly disintegrating world, we are also told that loneliness is inescapable and that it has a kind of aching fragrance to it that’s pleasant to dab on.

Like an idiot, I had forgotten that cologne came from Cologne. An hour and a half away from me by train, the city after the holidays this year was full of people, and the windows of the tourist shops gleamed with shining little bottles of the perfume, whose original maker, in the 18th century, described as redolent of “an Italian spring morning, of mountain daffodils and orange blossoms after the rain.” Would that I had smelled it—had smelled the source of the stuff my high school classmates used to throw on, in the form of Axe Body Spray, in hopes, I think, of not being lonely, of attracting the people who the scent actually, of course, repelled. But I did not stop to sniff, and went, instead, into a mall in the heart of the shopping district of Cologne, and from there up to the fourth floor, and into a museum-sponsored by a bank.

A bank in a mall was a weird place to find the largest collection of prints by the German artist, socialist, and pacifist Käthe Kollwitz, since her work is famously concerned with the agonies and struggles of the working class. In the old boardroom of the bank, Kollwitz’s work hung, some of it so blazing with grief and feeling it was hard, actually, to take. It was the day after the day after Christmas, and the exhibit, like Munch’s, was probably as thick with people as it got—in this case, because of the odd location, because maybe shared agony sells a little worse than individual agony, there was far less jockeying. Instead, visitors wandering through this bright space, past Kollwitz’s shrouded mourners and raging groups of weavers, walked in shared contemplation. There were no guards. The anger and grief in this room translated easily across time. But why its setting, in this bank? Can you imagine, in the United States, a Wells Fargo sponsoring a Käthe Kollwitz exhibit? Increasingly, I think, yes, I can—and it would make a great scene in Nathan for You. Only upon investigating later did I realize that the Sparkasse, the bank in which the Kollwitz museum sits, is a uniquely German public savings bank, locally operated, publicly accountable, and part of a large and popular system more than two hundred years old. Sparkassen (plural) operate under a mandate of public service, and are a far cry, in many ways, from Deutsche Bank—which claims, by name, of course, to be, well, the German bank. Sparkassen held strong in the initial throes of the Recession, and have helped in Germany’s recovery, and many of them are working, now, to finance the country’s transition to renewable energy. Reading about the Sparkassen, revisiting the Kollwitz exhibit, I was reminded of the individualism that we have been sold, now, for forever, but now more than ever, and all of the subsequent lonelinesses suffered in solitude and compounded by the various failures of healthcare, transportation, economy, environment. Mark Fisher called it the privatization of stress.

Anyway—now that I’m actually quite alone, I’m less interested in the glossy version of loneliness. Thoreau, no stranger to solitude, posed a helpful question, in Walden: “what sort of space is that which separates a man from his fellows and makes him solitary?” The answer, these days, is profit maximization. To the Sparkassen we go.