Of course Donald Trump wants a military parade. I’d be surprised if he didn’t. It’s just what an insecure narcissist would want. A parade would be the national equivalent of his strutting around like a peacock, dying to turn heads. Even a politician can see that: “I think confidence is silent and insecurity is loud,” Louisiana Republican Sen. John Kennedy said. “America is the most powerful country in all of human history; you don’t need to show it off.”

But harbor no doubts: Trump’s parade will be the biggest, best, and most-watched military parade in history — guaranteed. And I don’t mean just American history.

Let’s not forget that Trump declared himself the most “militaristic” candidate in the large Republican primary field. That was no small boast, considering that field included Lindsey Graham, Ted Cruz, and Marco Rubio. Trump couldn’t express his awe of the military, the marvelously murderous weaponry, and the valiant veterans often or heartily enough. Nothing animated him more.

Trump may have teased the voters with intimations of military retrenchment and nonintervention (like his two predecessors), but some of us knew he was not to be taken seriously. It was a pose, pure and simple. His opponents were parroting the establishment war-party line (with the occasional exception from Rand Paul), so Trump had to break from the pack. Every president had been an idiot, he said, getting us into all those stupid wars (each of which he favored before the fact) and spending all that money, which could have been spent here in America. He didn’t mean it. He’s a bullshitter — is there anyone left who does not know that?

You want evidence? Look at his first year in office. He’s hiked (with Congress’s enthusiastic help) the military — not “defense” — budget by an amount that exceeds Russia’s entire military budget: $81 billion versus $70 billion. He’s blurred the line between civilian and military by putting generals in key civilian positions. He’s shown an eerie fondness for tactical as well as strategic nuclear weapons. He has put troops — under NATO’s banner! — on Russia’s border. (Some Putin puppet he turned out to be.) He’s arming the government of Ukraine. His formal national-security strategy targets Russia and China. He has provoked Iran and North Korea. He’s doubled down everywhere his two immediate predecessors became embroiled militarily, including Syria, where his imperial stormtroopers are not welcome by the government of Syria. ISIS may be kaput, but Trump’s people say we’ll be hanging around to get rid of President Assad. So much for Trump’s repeated condemnation of regime change and his paeans to national sovereignty before the UN. They mean bupkis. What a conman he is. How did any libertarian fall for the guy?

So about that parade: I don’t know how the public will receive it. Of course the Trumpsters will love it, but so might many others who have zero stomach for the abominable one. The safest thing to do in America today is to express reverence for the military and thank the troops for their “service.” But what they do is no service to regular people — it’s downright dangerous actually — though it’s important service to the custodians of the empire, Trump included. Oddly, demanding the troops be taken out of harm’s way is more often than not branded unsupportive and even disloyal.

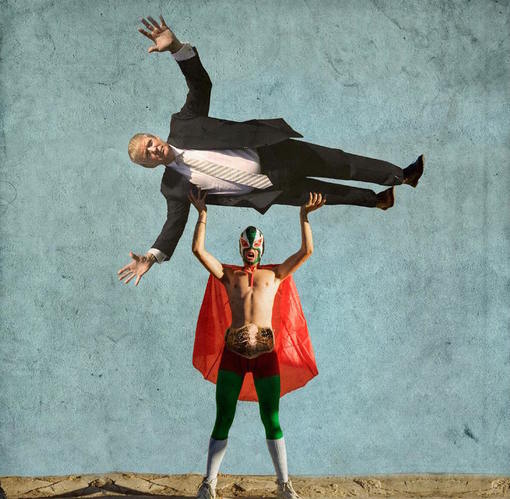

At any rate, the sight of costumed — forgive me — uniformed men and women in serried ranks, accompanied by missiles, tanks, and artillery, proceeding down Pennsylvania Avenue would likely send chills down the spine of many an American.

But perhaps things are not as bleak as I suspected. Politico reports that “members of Congress from both parties joined retired military leaders and veterans in heaping scorn Wednesday on President Donald Trump’s push to parade soldiers and weaponry down the streets of the nation’s capital — calling it a waste of money that would break with democratic traditions.”

Politico also quoted Paul Rieckhoff, CEO of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, which the publication calls “the largest group of post-Sept. 11 veterans”, saying: “This is definitely not a popular idea [with his members]. It’s overwhelmingly unpopular. Folks from all political backgrounds don’t think it is a good use of resources.” Rieckhoff expressed concern with “anything that politicizes the military.”

Will that deter Trump, the self-proclaimed champion (but cynical user) of veterans? Not bloody likely. Politico adds, “[Defense Secretary James] Mattis told a White House news briefing that preparations for a celebration are underway.”

Here’s the thing: a military parade that’s not even linked to the end of a war strikes me as deeply un-American. I say this despite my revisionist view of American history, for as the classical-liberal historian Arthur A. Ekirch Jr. wrote in The Civilian and the Military: A History of the American Antimilitarist Tradition (1956), “The tradition of antimilitarism has been an important factor in the shaping of some two hundred years of American history. This tradition, with its emphasis upon civilian against military authority, is accepted as an essential element of American freedom and democracy. Though involved in numerous wars, the United States has avoided becoming a militaristic nation [remember, this was written in 1956.], and the American people, though hardly pacifists, have been staunch opponents of militarism.” Ekirch is supported by the fact that the last three presidential winners called for a more “humble” (to use George W. Bush’s word) foreign policy, although they did not deliver.

After the Revolution the standing army was an object of popular suspicion, and it engendered opposition in Confederation Congress. When the Society of Cincinnati was organized to honor the revolution’s officers, the opposition was swift and widespread. “Almost at once,” Ekirch wrote, “the Society was criticized as an attempt to establish the former Revolutionary officers as a hereditary aristocracy, and the volume of protest soon reached impressive proportions.” Some Americans feared its members were planning a coup, and the immensely popular George Washington had to distance himself from the Society.

Unfortunately, the Constitution of 1789 did not forbid a standing army, and one was assembled. (Reluctance to be in the militia led some men to support a professional army.) “Three members of the Convention who refused to sign the final draft of the Constitution, Edmund Randolph, George Mason, and Elbridge Gerry, gave as one of their reasons its failure to set any limitation on a standing army…. The lack of more specific limitations, such as might be included in a bill of rights, plus the failure to prohibit a standing army in time of peace, were viewed as the two chief defects of the Constitution from the antimilitarist point of view,” Ekirch wrote.

James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, authors of The Federalist Papers, sought to allay fears that the Constitution would empower a menacing military establishment, Ekirch noted. But “after the Constitution was adopted, its staunchest supporters readily forgot the interpretation of the document that they had offered in the heat of the struggle for ratification. While the proponents of a strong centralized government lost no time in presenting to Congress their plans for a regular military establishment, the anti-Federalist opponents of the Constitution united to prevent the creation of a standing army.” The militarists did not get everything they wanted, but they got enough, and things grew from there with only occasional setbacks.

Meanwhile, generations of hysteria about imagined enemies, not to mention the pro-military propaganda in the government’s schools, the cinema, and the news media, extinguished the antimilitarist spirit that Ekirch documented. We must find a way to rekindle it.

Some people have proposed that Trump’s parade be postponed until all the wars the U.S. government is waging are finished and the troops are back home. That would indeed be an indefinite postponement, and I wouldn’t want to see a parade even then. But if that’s the price for ending those imperial wars, I’ll take it.