The chemical-intensive industrial model of agriculture has secured the status of ‘thick legitimacy’. This status stems from on an intricate web of processes successfully spun in the scientific, policy and political arenas. It status allows the model to persist and appear normal and necessary. This perceived legitimacy derives from the lobbying, financial clout and political power of agribusiness conglomerates which, throughout the course of the last century (and continued today), set out to capture or shape government departments, public institutions, the agricultural research paradigm, international trade and the cultural narrative concerning food and agriculture.

Critics of this system are immediately attacked for being anti-science, for forwarding unrealistic alternatives, for endangering the lives of billions who would starve to death and for being driven by ideology and emotion. Strategically placed industry mouthpieces like Jon Entine, Owen Paterson and Henry Miller perpetuate such messages in the media and influential industry-backed bodies like the Science Media Centre feed journalists with agribusiness spin.

From Canada to the UK, governments work hand-in-glove with the industry to promote its technology over the heads of the public. A network of scientific bodies and regulatory agencies that supposedly serve the public interest have been subverted by the presence of key figures with industry links, while the powerful industry lobby hold sway over bureaucrats and politicians.

Monsanto played a key part in drafting the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights to create seed monopolies and the global food processing industry had a leading role in shaping the WTO Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (see this). From Codex, the Knowledge Initiative on Agriculture aimed at restructuring Indian agriculture to the proposed US-EU trade deal (TTIP), the powerful agribusiness lobby has secured privileged access to policymakers to ensure its preferred model of agriculture prevails.

In her numerous documents, Dr Rosemary Mason has highlighted high-level collusion and subterfuge that has served to keep glyphosate on the commercial market. Claire Robinson and Jonathan Latham have described how an industry-backed campaign set out to smear science and scientists which were critical of proprietary technology. And Carol Van Strum and Evaggelos Vallianatos have indicated fraud and corruption involving the US Environmental Protection Agency that have resulted in industry interests prevailing at the expense of public health and the environment.

On a wider more geopolitical level, Michel Chossudovsky has examined how transnational agribusiness working with USAID effectively dismantled indigenous agriculture in Ethiopia. Ukraine’s agriculture sector is being opened up to Monsanto. Iraq’s seed laws were changed to facilitate the entry of Monsanto. India’s edible oils sector was undermined to facilitate the entry of Cargill.

Whether it involves the effects of NAFTA in Mexico or the ongoing struggle against the Monsanto across South America, traditional methods of farming are being supplanted by globalised supply chains dominated by transnational companies policies and the imposition of corporate-controlled, chemical-intensive (monocrop) agriculture.

The ultimate coup d’tat by the transnational agribusiness conglomerates is that government officials, scientists and journalists take as given that profit-driven Fortune 500 corporations have a legitimate claim to be custodians of natural assets. These corporations have convinced so many that they have the ultimate legitimacy to own and control what is essentially humanity’s common wealth. There is the premise that water, food, soil and agriculture should be handed over to powerful transnational corporations to milk for profit, under the pretense these entities are somehow serving the needs of humanity.

Tearing down the façade of legitimacy

In recent times, Dr Rosemary Mason has been campaigning against the effects of agrochemicals on human health and the environment. She has a nature reserve in South Wales and noticed that flora and fauna was becoming increasingly degraded to the point that the reserve now resembles little more than a dead zone in comparison to what it had once been.

In her dozens of carefully researched and fully-referenced letters to key officials in the UK, EU and US, Dr Mason has documented the effects agrochemicals on her nature reserve as well as on health and the environment not only in Wales but globally.

She has, moreover, gone to great lengths to describe the political links between industry and various government departments, regulatory agencies and key committees that have effectively ensured that ‘business as usual’ prevails.

Mason recently received a response from Public Health England (PHE) to this open letter she had sent to the four chief medical officers for England, Scotland Wales and Ireland. The PHE inquiries team which responded to Mason failed to answer any of her questions about the cozy relationship between the British government, the agrochemical corporations, the pharmaceutical industry and the corporate media.

The response did not even acknowledge the warning given by the UN Human Rights Council about the dangers of pesticides in food and water and how this especially undermines the development and rights of children.

Not to put too fine a point on it, the PHE reply is along the lines of thanks, now move along because officialdom has everything covered.

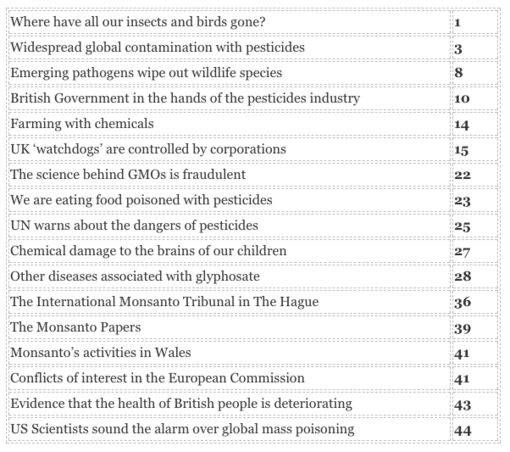

Clearly, given the concerns raised by Mason, things are not ‘covered’. In a new letter to the chief medical officer for England, she spells out the unsatisfactory nature of the response received from PHE and also attaches this 45-page document that sets out why the response is both inadequate and wholly flawed. The contents of Mason’s document are below. Readers are urged to read the document in full as well as her initial open letter to PHE.

But is this any surprise? The corporations which promote industrial agriculture and the agrochemicals Mason campaigns against have embedded themselves deeply within the policy-making machinery on both national and international levels. The US government has indeed promoted an exploitative ‘stuffed and starved‘ strategy that weds consumers and farmers across the world to the needs of transnational agribusiness and its proprietary inputs.Whether it concerns PHE or any of the other bodies Mason has written to over the years, any response she has received is usually quite dismissive of her concerns.

From the overall narrative that industrial agriculture is necessary to feed the world to providing lavish research grants and the capture of important policy-making institutions, global agribusiness has secured a perceived thick legitimacy within policymakers’ mindsets and mainstream discourse.

If you – as a key figure in a public body – believe that your institution and society’s main institutions and the influence of corporations on them are basically sound, then you are probably not going to challenge or question the overall status quo. Once you have indicated an allegiance to these institutions – as such figures do by the very fact they are part of them and often receive good salaries as employees – it is ‘irrational’ to oppose their policies, the very ones you are there to promote.

And it becomes quite ‘natural’ to oppose with dogmatic-like zeal any research findings, analyses or questions which question the system and by implication your role in it. Little surprise therefore that Rosemary Mason appears to run into a brick wall each time she raises issues with key figures.

But once you realise and acknowledge that the integrity of society’s institutions have been eroded by corporate money, funding and influence – and once you are in a position to offer a credible alternative to corporate agriculture and all it entails based on authentic values that are diametrically opposed to those of corporate conglomerates – you can ask some very pertinent questions that strip away perceived legitimacy.

The questions being asked by Rosemary Mason and others are part of the wider process of stripping away the fabricated reality and perceived legitimacy that the whole system of industrial agriculture rests on.