Photo by Rob Kall | CC BY 2.0

On January 1, 2018, some of Hollywood’s most prominent women, including Reese Witherspoon, Shonda Rhimes, and Natalie Portman, launched an initiative called Time’s Up to address “sexual assault, harassment and inequality in the workplace.” This commendable initiative intends to financially subsidize legal support for women and men who lack resources. White celebrity women brought women leaders (all women of color with the exception of Billie Jean King) to the Golden Globes on January 8, 2018 to promote Time’s Up and important activist causes. But is this feminist progress, especially when none of the male award winners directly acknowledged Times’s Up in their speeches? How do we make sense of this moment of solidarity among women alongside the deafening silence of men and the simultaneous political rollbacks throughout the country?

As feminist scholars of women’s organizing, we’re concerned that too often the story about women coming together is told in a form of linear progress: women come together, change happens, the end. But a far more complicated and compelling story about what’s possible when women come together, and the work that remains deeply unfinished when they do, is a fundamental component of any assessment of feminist progress.

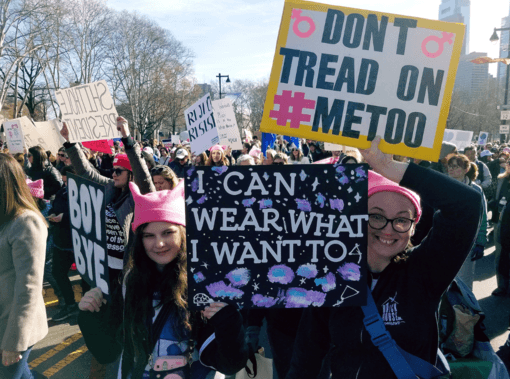

Buried at the end of The New York Times story about Time’s Up is a revealing quote: “members said the meetings had brought disagreements and frustrations as well.” How then should we understand feminist progress following what would seem to be an exemplar year for women’s organizing that included the largest single day gathering of protesters for the Women’s Marches and the #MeToo movement where scores of women publicly revealed their experiences with sexual harassment and violence that resulted in firings and resignations of some high profile men?

We need to stop viewing women’s organizing as either only successes or failures when often the reality is some combination. For example, the Women’s Marches had an initial call that fell short in addressing the experiences of women of color, immigrant women, and transgender women. Yet after a series of interventions by seasoned antiracist feminist organizers, the final platform was fantastically comprehensive.

Unfortunately, too many people from the marginalized communities represented in the platform were not able to participate in the marches. Still the hundreds of thousands–likely even millions–of people of all genders who took to the streets on January 21, 2017, including us, experienced joy and euphoria at being together and confronting this reckless administration en masse.

In retrospect, many organizers realized that they had not sufficiently accounted for the accessibility needs of disabled participants. Taken together, the trajectory of organizing for this massive protest demonstrates that feminist progress is non-linear, dynamic, and circuitous.

The 2016 Presidential election made it clear that we have a race and misogyny problem in this country and a rather magnificent one. Exit polls reveal that 52% of white women voted for Trump and Pence whereas 4% and 28% of Black women and Latinas voted for them, respectively. Viewing women as a homogenous group misses the fact that white women are deeply divided politically, indicating that any kind of cross-racial feminist organizing won’t involve the majority of white women until more of them reject what New Zealand Maori scholar Brendan Hokowhitu calls the “heteropatriarchal dividend.”

This dividend offers perceived societal power and is acquired by actively participating in and benefiting from a heterosexist, patriarchal and racist society. It is imperative that any discussion about women coming together acknowledge this uncomfortable truth. White feminists must challenge other white women on their internalized misogyny and racism because women of color organizers, like 27-year old police brutality activist Erica Garner (daughter of Eric Garner who was killed by New York police officer Daniel Pantaleo in 2014), too often lose their lives in antiracist struggles.

Finally, current media reports about sexual harassment and assault are suggesting that our culture is on the verge of major change regarding sexual harassment because we’ve seen the spectacular downfall of a few famous men and celebrities are speaking out, with a few openly supporting women activists at a recent high profile event. But these moments are too fleeting. While we understand that celebrities can garner media attention, feminist scholars such as Hillary Haldane, Kimberlé Crenshaw and Catherine McKinnon, anti-violence advocates in communities across the nation, and organizations such as SONG (Southerners on New Ground) and Black Youth Project 100 are doing the work, generally without fanfare, that needs to inform feminist organizing in the current moment. Decades of work by feminist activists and scholars underscore the enormous challenge in changing our patriarchal and racist culture, a challenge that is ignored when spotlighting individual-level changes.

Although we understand the appeal of stories about women coming together to overcome adversities, we also know that we must reckon with a more honest narrative that represents the promises and challenges when women work together. Understandings of women’s progress in 2018 and beyond must include moments of exhilaration as well as the profound disappointments which demonstrate that a linear narrative of feminist progress is misleading.

A linear narrative cannot explain how the majority of white women voted for a presidential ticket that included a racist, inexperienced, and self-professed predator of women in the same year that we also had the Women’s Marches and #MeToo.