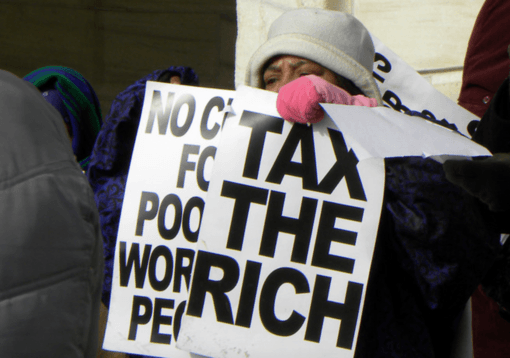

Photo by Fibonacci Blue | CC BY 2.0

It now appears likely that the Republicans will get their tax cuts through Congress and signed by President Trump. This will be a political accomplishment for congressional Republicans who feel a need to deliver a tax cut to their wealthy campaign contributors. Its economic impact is far less clear.

The line from the Republicans is that the tax cut, most of which takes the form of a reduction in the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 20 percent, will lead to a huge burst of investment. The logic is that lower tax rates will increase the after‐tax return on capital, causing foreign investment to flood into the country.

This investment will mean more economic growth, and most importantly, higher productivity, which will be passed on to workers in the form of higher wages. President Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers predicts that the gain in wages for an average worker can be as much as $4,000 a year.

There are good reasons for believing that nothing like this will occur. There is a great deal of evidence that investment is not especially responsive to changes in profit rates. For example, there has been a large increase in the after‐tax profit rate over the last fifteen years as a result of a huge redistribution from wages to profits. In spite of this rise in the profit rate, investment has been relatively lackluster over this period.

We did also try this experiment before. In 1986, the corporate income tax rate was lowered from 46 percent to 35 percent. Rather than prompting a flood of new investment, it actually fell for the next two years. It’s not plausible that the tax cut caused this drop, but it is clear that we didn’t get any big burst in investment three decades ago. Why would we expect anything different this time around?

If the story the Republicans are telling about the tax cut doesn’t make much sense, the deficit fears pushed by the Democrats also don’t deserve to be taken seriously. According to the projections from the Congressional Budget Office, the tax plan will add a bit more than $1 trillion to the debt over the next decade.

This is being touted as a huge burden that our children will have to bear. That doesn’t add up. If we assume an average interest rate on government debt of 3.0 percent, this comes to an annual interest burden of $30 billion. In a decade, GDP will be over $25 trillion. This means the additional interest burden from this tax plan will be a bit more than 0.1 percent of GDP.

By comparison, every day of the week the government is granting patent and copyright monopolies that allow the holders to charge prices that are far more than the free market price. This is most notable in the case of prescription drugs where the patent‐protected price can easily be 100 times the free market price.

In the case of prescription drugs alone, government granted patent monopolies add around $370 billion a year to the price of drugs, almost 2.0 percent of GDP. The total cost when we add in sectors like medical equipment, software, and entertainment is certainly at least two or three times as large. It makes no sense to complain about an interest burden of a bit more than 0.1 percent of GDP, while completely ignoring burdens from patent and copyright monopolies that can be 40 or 50 times as large.

While neither the story of an economic boom or economic disaster makes sense, this tax bill is still very bad news. First and foremost, even if deficits are not an economic problem, they are a political problem.

Promoting fear of deficits is one of the major industries in Washington. The larger deficits created by the tax cut will be used as a reason to cut a wide range of social welfare programs, such as Social Security and Medicare. Some of these cuts are actually mandated under current law.

The bill also includes a major hit to the Affordable Care Act, ending the mandate that people have insurance. This is estimated to leave 14 million more people without health care insurance.

In addition, the law was structured to hit more liberal states in every way imaginable. The most important item is ending the deduction for state and local income taxes. This will make it more difficult for relatively liberal states, like California and New York, to fund social services.

The bill also creates huge new opportunities for gaming the tax code. It allows anyone who gets their income through a “pass‐through” corporation to pay 23 percent less in taxes.

Pass‐through corporations are corporations that enjoy the privilege of corporate status but pay zero income tax. This was already hard to justify. If you get the privileges of corporate status, why shouldn’t you be taxed like a corporation?

But the new tax bill makes the inequity enormously worse, giving people who own pass‐through corporations 23 percent off their tax bill. Look for a boom in the creation of pass‐through corporations.

The bottom line is that this tax bill is about giving more money to the richest people in the country. These are the people who have received the bulk of the gains from the last four decades of economic growth. Now the Republicans are determined to give them even more.

This article originally appeared The Hankyoreh (S. Korea.)