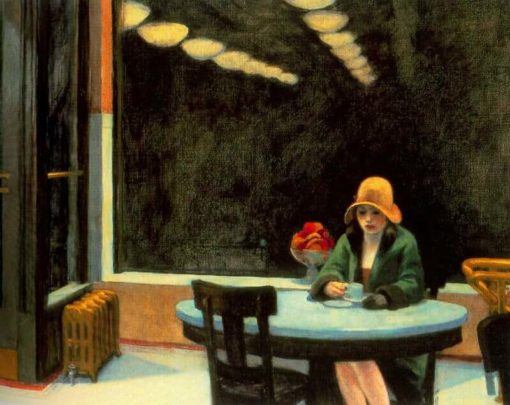

Automat by Edward Hopper (1927).

When I lived in Chicago, I often went to the Art Institute to admire the paintings of Edward Hopper, especially Nighthawks. Later on, I would do the same thing in New York, at the Whitney; both galleries have excellent Hopper collections. I remembered those visits when, in full lockdown, social media were flooded with images of this painter’s work. I asked myself: why is it Hopper, precisely, who is speaking to us from such close quarters during this period?

Edward Hopper is the painter of solitude. Of solitude and isolation. Whereas some languages, like Spanish, have only one word, ‘soledad’, the English language has a near synonym for solitude: loneliness, meaning a sad, unwanted solitude. The same two words exist in Czech: ‘samota’ – ‘osamelost’. There are surely many different opinions about this, but as far as I’m concerned, Hopper paints both types of solitude.

Nighthawks shows four people in a bar late at night: a man and a woman who are not a couple, sitting together; and another man sitting a little further away along the bar, each person absorbed in his or her own melancholy mood. The barman puts the finishing touch to this image of desolation: he is washing glasses and even though he’s answering a question somebody’s asked him, his demeanour shows that he’s not interested in making small talk: he wants these last few customers to leave as soon as possible; whereas they know that if they abandon the piercing silence of the bar, they will feel more desolate than ever. The characters in Nighthawks are an example of solitude in the sense of loneliness. As is The Hotel Room: a tired woman who is reading in a hotel room, her bags still unpacked, a detail which gives a temporary feel to the setting. The woman in Automat is sitting at night in an empty cafeteria; her anguish is there for all to see, emphasized by the fact that she has only removed one glove.

glasses and even though he’s answering a question somebody’s asked him, his demeanour shows that he’s not interested in making small talk: he wants these last few customers to leave as soon as possible; whereas they know that if they abandon the piercing silence of the bar, they will feel more desolate than ever. The characters in Nighthawks are an example of solitude in the sense of loneliness. As is The Hotel Room: a tired woman who is reading in a hotel room, her bags still unpacked, a detail which gives a temporary feel to the setting. The woman in Automat is sitting at night in an empty cafeteria; her anguish is there for all to see, emphasized by the fact that she has only removed one glove.

Melancholy, instability, unease: words which describe the mood of many of Hopper’s paintings. Paintings which are a perfect example of what is known as ‘liminal space’. The word ‘liminal’ comes from Latin: limen means ‘threshold’, so a ‘liminal space’ is one which lies beyond the world with which we are familiar. In liminal spaces, one feels that one is out of kilter, in uncharted territory. It is a transitional space-time which can eventually change people. Bars, airports, train or plane journeys and hospitals can all be examples of liminal spaces, which almost always involve travelling through time. As is the case with the Davos sanatorium which Thomas Mann described in The Magic Mountain, in which the patients try to cure their tuberculosis while transforming themselves in the process.

During lockdown, I looked at Hopper’s paintings on my computer screen and felt that they were all located in liminal spaces. I became more sharply aware of this after quarantine, that time when we were all confined to our homes, barely being allowed to go out. It was a transition between two realities: one which was familiar, the normality we left behind three months earlier; and another, as yet unknown, waiting inevitably for us once our temporary, solitary period of lockdown comes to an end. In this liminal space of obligatory self-isolation, as the media bombarded us with defiant messages about the fearful world that we will discover when the lockdown is over, we feel like Hopper’s characters: alone and uneasy about the world which awaits us.

In our unstable word, which Zygmund Bauman so lucidly described as liquid, Hopper is the painter who best expresses our anxious solitude. Today, his paintings are nothing less than prophetic.