Yosemite Falls, Yosemite National Park. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

I visited Yosemite National Park recently. I was dismayed to see the logging of large trees in the valley. According to the Park Superintendent, the justification for logging is “to use every tool at our disposal to save the forests and to save the park and to restore a healthy ecosystem and to keep people safe.”

The proposed logging has been temporarily halted by a lawsuit from the John Muir Project.

The National Park Service (NPS) also says they are “restoring a historical view” as if the fact that trees have grown up obscuring the vista is somehow part of the NPS mandate. (Maybe we should restore the “historic” view of grizzly bears feeding at the dumps in Yellowstone too.)

Indeed, much of the justification for logging is to “restore” the forest to its “historic” condition created by Indian burning. However, there are numerous problems with this goal.

Proponents of logging and prescribed burning suggest they are recreating historical forest conditions and assert that today’s forest stands are overly dense and, thus, more susceptible to mortality from fire, drought, and insects.

However, some ecologists question those assumptions and claim that the common assertion that forests were more open and park-like is an exaggeration and misinterpretation of early forest surveys.

Natural evolutionary processes like drought, insects, and wildfire tend to “thin” the forests and are much better at picking the specific individuals with or without adaptations to survive under the new climatic conditions.

The fundamental issue is whether the Park Service should be a gardener or a guardian. The logging of forests to “restore” them is like the gardener weeding a vegetable patch. It may be appropriate where humans are trying to favor certain plants over others, but is this the mission of the NPS?

Rationalizing logging and burning because Indians once manipulated the Yosemite landscape is a dangerous premise. Why just Indians? Ranchers also grazed Yosemite’s meadows. Shouldn’t we “restore” the meadows with sheep?

All these kinds of justifications for human manipulation assume that forests cannot possibly survive without human interference.

However, humans only colonized North America perhaps 15,000 years ago, but the forests in the Sierra Nevada existed for millions of years without any human manipulation. They did just fine without human interference.

Furthermore, there is a lot of debate about the actual influence of Indian burning on the landscape, both in Yosemite and elsewhere.

For example, Vachula et al. reviewed the fire history of what is now Yosemite National Park, where, historically, large Indigenous communities resided. Their research found a direct correlation between climate and the amount of burning on the landscape.

“We analyzed charcoal preserved in lake sediments from Yosemite National Park and spanning the last 1400 years to reconstruct local and regional areas burned. Warm and dry climates promoted burning at both local and regional scales….”

The researchers say, ” Regional area burned peaked during the Medieval Climate Anomaly and declined during the last millennium, as the climate became cooler and wetter and Native American burning declined.”

They concluded with: “Our record indicates that (1) climate changes influenced burning at all spatial scales, (2) Native American influences appear to have been limited to local scales, but (3) high Miwok populations resulted in fire even during periods of climate conditions unfavorable to fires. However, at the regional scale (< 150 km from the lake), fire was generally controlled by the top-down influence of climate.”

Earlier, geographer Thomas Vale came to similar conclusions.

The question is whether our national parks are supposed to be “museum pieces” or places where evolutionary and ecological processes prevail.

If it is the latter, then “saving” forests from wildfire by logging contradicts this goal.

For one thing, the NPS, like the Forest Service, has no idea which trees have evolutionary and genetic adaptations to wildfire, insects, drought, and other sources of mortality. Random removal of trees could eliminate rare genetic alleles and degrade the resilience of the forest ecosystem.

Furthermore, it is essential to note that evolutionary and natural processes like wildfire produces substantial amounts of snags and down logs which are critical to ecosystem health. The idea that dead trees represent “unhealthy” conditions is an Industrial Forestry perspective and has no place in a national park.

In addition, both live and dead trees store carbon. Logging has been shown to increase carbon emissions, and most studies that proclaim to “save” trees never consider the loss of trees (and carbon storage) that is a consequence of thinning/logging projects.

I understand why Park administrators may be nervous about wildfires in Yosemite Valley. However, if a blaze were to start under extreme fire conditions with high winds, low humidity, and high temperatures, it might be impossible to get people safely out of the valley.

All the Yosemite entrances involve driving on twisty mountain roads. All it would take to stop traffic is for one or two cars to run out of gas and be abandoned on the road. In addition, people fleeing a wildfire are likely to drive exceptionally fast, increasing the possibility of accidents or even the car and passengers flying off the side of a cliff.

However, unless you log all the trees and pave the valley, there will always be the risk of a major conflagration. Research has shown that logging not only does not preclude large blazes but can favor them, with protected areas typically having less severe fires than previously logged areas.

The more significant danger I see with the Yosemite logging program is its threat to the National Park mandate to preserve ecological function and evolutionary processes. Wildfire is one of those processes. The drought conditions now dominating the West create favorable conditions for massive wildfires. Wildfires and other sources of mortality represent the landscape “adapting” to the new climate realities.

I understand the desire to preserve sequoia groves through prescribed burning, setting up sprinklers, and doing whatever it takes to protect these giants. There are only 75 sequoia groves in the entire Sierra Nevada. Perhaps in those rare situations, such manipulation might be justified (depending on precisely what is proposed) just as we might want to preserve the last condors by captive breeding.

However, most of Yosemite’s forests do not consist of relatively rare trees like a sequoia.

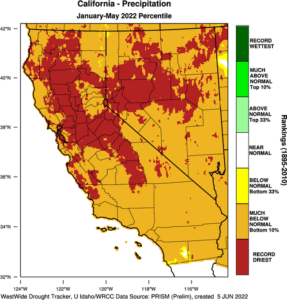

The red areas of this map which includes Yosemite NP shows that much of the West is experiencing the worse drought in over 1200 years. And climate change, not fuels, is responsible for large blazes.

Rather than manipulate the forests, Yosemite National Park should stand back and let natural processes determine the density of trees, which species are best suited to the new realities, and watch the results.

Ultimately, we cannot manipulate (by logging or burning) our way out of the current climate warming scenario. Our best alternative is to preserve natural processes, not museum pieces.