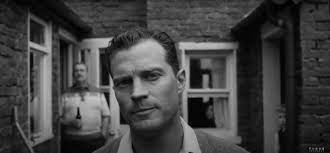

Still from Belfast.

Belfast, written, invented, and directed by Kenneth Branagh, is the story of a white, Protestant family in Belfast in 1969—In Northern Ireland—at a time of mass, Catholic civil rights demonstrations against British-supported Fascist Protestant “Unionists.” In response, the family stands by and does nothing, engages in hackneyed, cloying, family rituals, eats potatoes, drinks beer, declares their love for Protestant Belfast, and eventually leaves for London to escape the deterioration that the British and Unionists had inflicted on the city.

This is the first in Branagh’s Heinous Trilogy. It will be followed by Birmingham, the story of a white Protestant family who witness the fire hoses, dogs, and murder of four Black children, see the Civil Rights Marchers in the streets, stand by and do nothing, engage in hackneyed, cloying rituals, drink beer, eat white bread with mayonnaise, declare their love for the white South, and finally move to Meridian, Mississippi where they do nothing as the Black revolution is burning up history.

This will be followed by Branagh’s already acclaimed classic, Berlin, the story of a white Protestant Aryan family who witness the Jews being taken to the concentration camps, see the Communists and Sophie Scholl leading the resistance, stand by and do nothing, engage in hackneyed, cloying family rituals, eat brats, drink beer, declare their love for Aryan Berlin, and eventually move to Buchenwald to build a new life.

When I first heard about the film Belfast, with some appreciation of Kenneth Branagh (except for his actual life) and assuming this to be a film sympathetic to the IRA, I paid my $20 for streaming which is now my fee for first-run films at home in the age of Permanent Pandemic. Why I had that fantasy is a product of my revolutionary hope and vulnerability to capitalist marketing.

Belfast opens with white fascist Protestants attacking the Irish Catholic minority in brutal thuggish pogroms. That is it. No context, no explanation of the specific abuses of the Ulster Protestant loyalists and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the overwhelmingly Protestant police force. No portrayals of Catholic resistance. Nothing. This is a conscious device by Kenneth Branagh, to make a film about Belfast in 1969, in the midst of a bloody civil war, and avoid all references to history—with Van Morrison singing songs that have nothing to do with anything.

Since I can’t critique Belfast without myself learning more of the history, I’m appreciative of several Wikipedia articles that lay out the story succinctly.

The History that Belfast chooses to cover up.

Northern Ireland—a construction of the British Empire—is separated by a border with the Irish Republic, which is majority Catholic. Northern Ireland and Belfast are majority Protestant, most of whom identify as Unionists, meaning the union with Great Britain versus a union with The Irish Republic. The vast majority of Irish Catholics were demanding civil rights and equality, with some supporting self-determination and alliance with Ireland, but all seeking full democratic rights inside Northern Ireland. A major Civil Rights Movement, as the Black movement encouraged resistance all over the world, was led by groups like The People’s Democracy, with heroic figures like Bernadette Devlin and thousands of others who carried out a sustained and effective resistance. In 1969, the very year in which the film is situated, the Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV), a paramilitary force allied with the fascist Ian Paisley, bombed water and electricity installations in Northern Ireland, leaving much of Belfast without power and water. They also attacked and killed several Catholics and vehemently opposed the growing Irish Catholic led Civil Rights Movement.

In 1969, there was a “Long March” from Belfast to Derry modelled on the civil-rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

“The purpose of the march was described by one activist as “pushing a structure…towards a point where its internal proceedings would cause a snapping and breaking to begin” while Devlin described it as an attempt to “pull the carpet off the floor to show the dirt that was underneath” The march was attacked repeatedly along the way, but as it developed it drew more supporters and participants. By marching through “Protestant territory” (where it was repeatedly blocked and threatened), the Long March exposed Northern Irish brutality and the unwillingness of police to defend the right to protest. As they neared Derry, at Burntollet Bridge, the marchers were ambushed by loyalists and members of the RUC. Eighty-seven activists were hospitalized. When the marchers reached Derry, the city exploded in riots. Following a night of rioting, RUC men entered the Bogside (a Catholic ghetto), wrecked a number of houses and attacked several people. This led to a new development: Bogside residents, set up “vigilante” groups to defend the area. Barricades were put up and manned by the locals for five days. It also created a context in which older Republican veterans could emerge as prominent figures within the movement; for example, Sean Keenan (later important to the Derry Provisional IRA) was involved in pushing for defensive patrols and barricades.

In return, the government introduced more-repressive legislation (specifically banning civil-disobedience tactics such as sit-ins), which gave the movement something else to resist. In April there were more serious riots in Derry, and the barricades went up again for a brief period. Meanwhile, direct action around concrete issues continued; according to Devlin, in the first half of 1969 the activists around Eamonn McCann “housed more families [via squatting] than all the respectable housing bodies in Derry put together” In mid-1969 Prime Minister Terence O’Neill resigned and was replaced by James Chichester-Clark, who announced the introduction of “one man, one vote”; the civil-rights movement had achieved its key demand. However, additional demands concerned police violence and state repression. Two of the most prominent issues were the Special Powers Act, which gave nearly-indiscriminate power to the state (including internment without trial) and the B-Specials, a part-time auxiliary police force seen as sectarian and made up exclusively of Protestants.

This organizing led to a pitched Battle of the Bogside where the civil-rights movement became a localized insurrection against the state. When the RUC retreated and the British Army respected the barricades, there was a sense of victory. Bernadette Devlin (who took part) recalled:

“We reached then a turning point in Irish history, and we reached it because of the determination of one group of people in a Catholic slum area in Derry. In fifty hours, we brought a government to its knees, and we gave back to a downtrodden people their pride and the strength of their convictions.”

Given the grotesque misinformation of Branagh’s Belfast, and the need for all of us to learn so much more about this history, two of many post-scripts to the real story are helpful.

Bernadette Devlin and the Black Panthers

When Bernadette Devlin, elected to Parliament, went on a tour of the United States, yes, in 1969!, she allied with the Black-led Civil Rights Movement and made her primary association with the Black Panther Party. She wanted to make clear that the movement for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland was allied with the Black revolutionary movement and revolutionary movements all over the world. She took on the sadly racist and anti-communist U.S. Irish majority, danced with a Black man on stage, and was called “Fidel Castro in a miniskirt” which she took as a (male chauvinist) compliment. The point is that Devlin, who had her differences with the armed struggle wing of the Irish liberation movement, and them with her, is one of many Irish Catholic resistance fighters who should have been in the film, and our consciousness. She symbolized a fight for socialism and Black Liberation in the U.S. This would have been a great coda to the Belfast whose story deserved to be told.

Bernadette Devlin and Her Husband, Michael McAliskey, were shot and almost murdered by fascist thugs from the Ulster Defense Association with the express encouragement of Great Britain.

On 16 January 1981, Devlin and her husband, Michael McAliskey were shot by members of the Ulster Freedom Fighters, a cover name of the Ulster Defense Association (UDA), who broke into their home near Coalisland, County Tyrone. The gunmen shot Devlin nine times in front of her children. British soldiers were watching the McAliskey home at the time, but they failed to prevent the assassination attempt. It has been claimed that Devlin’s assassination was ordered by British authorities and that collusion was a factor. An army patrol of the 3rd Battalion, The Parachute Regiment entered the house and waited for half an hour. Devlin has claimed they were waiting for the couple to die. Another group of soldiers then arrived and transported her by helicopter to a nearby hospital. By a miracle, she and her husband survived.

Truly, this is the Belfast we deserve to see.

So, in the wake of the real world let’s take a look at Branagh’s fictitious Belfast.

Belfast begins with Branagh’s mythical family of supermodels. It begins with “Ma” played by the gorgeous Caitriona Balfe, a fashion model and the heroine of the series Outlander. She is married to, not surprisingly Pa, played by Jamie Dorman, also Irish who was also a fashion model who then played, I’m not kidding, “Christian” Grey in Fifty Shades of Grey. So, there they are—your typical working-class couple of movie stars. Then Branagh cast cute—as-kitten Jude Hill to play their youngest son Buddy (who we assume was Kenny when he was 9). Buddy is set up to steal the show with his pretty face and captivating smile. Finally, to round off this typical working-class Protestant family is Granny, played by Judi Dench and Pop by Ciararan Hinds, such highly respected actors in politically and dramatically demeaning roles.

Branagh’s casting was modeled on the work of Leni Riefenstahl.

At least at the outset, we are dying to love this family.

But from the first scene, there is trouble—and Trouble. A vicious Protestant mob is attacking the minority Catholics in Belfast in a violent pogrom, as the Catholics are terrified captives with nowhere to go. Now, Ma and Pa Protestant do not agree with these attacks. Neither do they do anything to oppose them. Then the film moves to the “smaller screen” of the nuclear family isolated from history. It turns out beautiful Ma has been paying off the bills run up by handsome Pa. She is so proud that after years of monthly payments she asks the bank for a statement that she has paid in full, only to find out that her husband had lied to her by not telling her that it will take more years to pay it off. Ma is furious and breaks plates in protest.

But after that dust-up, the relationship goes back to normal. Pa, facing very depressed working opportunities in Belfast, is a contract worker who commutes to London for two-week stints. The bus ride alone is 16 hours round trip. He is a good worker, a good father, and in his own way, a good husband. He is clearly a good guy in this film.

But while Pa is away, his family, as much as they try to live a normal life, can’t avoid the constant turmoil as the Protestant majority just can’t stop themselves from attacking and abusing the Catholics who do nothing to resist. Buddy goes to school, is a good kid, always smiling, and is a good student. He gets along with everyone and has a crush on Catherine, his schoolmate (played by Olivia Tennant.)

At school, the teacher places the students in rows of two based on their grades—with the best students at the head of the class and the worst, far back 10 rows or more. Buddy, who is already an excellent student, sits in the second row. And yet, his hoped-for girlfriend Catherine sits in the first row. So, his goal is to get to the first row, both for his own achievement but mainly to sit next to Catherine. So, Grandpa has a brilliant idea. In one of many cringe-worthy speeches, he tells Buddy,

“You know, the key to doing well in math is to make your numbers unintelligible so the teacher can’t figure them out. Make your 1 look like a 9, your 7 like a 5, your 6 like an 8, she’ll have to give you a great grade because she won’t know one number from another.”

So, imagine, if the correct answer is 3,751, Buddy’s answer could look like 9,425, 8,750, or anything but 3,751. This is of course a recipe for disaster. But to continue the charade in the script, when the teacher is giving out the grades she tells Buddy, “well, you need to work on your penmanship but I am putting you at the top of the class.” (Only white Protestants could even imagine such an outcome). But to Buddy’s chagrin, Catherine, who carried out the old fashioned get-the-correct-answer and write-your-numbers-legibly approach, is demoted to the second row so poor Buddy is thwarted again.

Now, sweet Buddy falls under the influence of his mischievous cousin, Moira, (played by Lara McDonnel.) Moira tells him he should join her gang and he enthusiastically agrees. In his first initiation, they all shoplift and Buddy brings home the spoils—but he is identified and charged by the shop keeper. The police come to the house to scare the hell out of him but behind his back, with a wink and a nod to his parents, they just think that (Protestant) boys will be boys.” Needless to say, a working-class Catholic kid in Belfast would be placed in juvenile prison.

In a subsequent scene, Moira tells Buddy that, because he did not rat out his co-thieves, he is being promoted in the gang. Here is his great opportunity, to join their rampage through the streets to attack an Indian grocer. Moira explains to Buddy,

Buddy, I didn’t tell you this but our gang is a fascist youth group and we hate Catholics but right now we plan to go to an Indian grocer and smash his store and steals his merchandise because he is a foreigner and we are Protestants and we hate everybody and this is great, right?

And Buddy Branagh keeps acting confused. (I thought he was an A student, what about “we’re a fascist gang about to attack an Indian man” did he not understand?) So as the gang runs through the streets, and attacks the Indian man’s store with a mob vengeance, screaming epithets, breaking windows, destroying the entire structure of the store, and stealing merchandize. Buddy, always the reluctant accomplice, finally accedes to group pressure, and steals a big bag of flour to bring back to his family.

Now, here is one of the most moving scenes of the film. As Billy brings back the stolen property Ma Supermodel is truly outraged. “We do not ever steal. Where did you get this? You must return it”. And outraged as all good Protestants must be about looting (except from the colonies) Ma drags Billy back into the mob riot to return the flour. She does nothing to stand up to the fascists. Of course, she does not tell Buddy, “Stop acting so confused, you knew damn well what you were doing.” She does nothing to help the Indian shop owner, but in the midst of chaos, returns a bag of flour into the rubble. Somehow, this is a story about character.

Now, the leading fascist organizer, Billy Clanton (played by Colin Morgan) the evil Protestant Unionist, threatens Pa in the streets. “In this war against the Catholics you are either with us or against us and if you are not sufficiently anti-Catholic I will have to hurt you.”

But “Grey” Pa stands up to him. In one of the most moving speeches in the film, he says,

“If I choose to do nothing that is my business. I stand for nothing. I do nothing. I think about nothing but myself and my family and no, I do not want to hurt the Catholics. But you do, Fine. Do I stop you? Do I stand in your way? Do I help the Catholics? No, I do nothing. So, get the hell out of here or I will fight to the death for my right to do nothing.”

But as the economic conditions get worse, and The Troubles Intensify, Ma and Pa have a heart-rending debate about their future. Pa, coming back from London says,

“Look I have a great opportunity. They want me in London. They will give me a real job with benefits and we can buy a home, get out of debt, and get out of Trouble. I’m tired of being accused of not hating the Catholics enough, tired of being in debt. We can have a home with a yard and a white picket fence in London, the center of the empire, and live happily ever after.”

But Ma, demanding from Branagh her own moving speech, replies,

“But Pa, Belfast is our home. We grew up here as toddlers and have loved each other since kindergarten. Sure, we can have a front yard in London, but here the kids can play in the street with no fear because they are Protestant. And I can always find them because they are not Catholic. And when we go to London they will never respect us. They will laugh at our Irish accent, never fully accept us a British, even though we love the British Empire. Sure, the beatings of the Catholics can be a distraction but honey, Belfast is our home, we belong here. Maybe we are in debt, maybe you are gone for two weeks, maybe Buddy has joined a fascist gang, but we love it here.”

Finally though, the pressures get too great and the opportunities become too enticing. Pa convinces Ma it’s time to go to jolly old London where they can do nothing while the British Protestants and Her Majesty’s Police beat up the West Indians, the Africans, and the Pakistanis while the British Black Panthers and the Mangrove Nine lead the resistance.

Now that Pop has died, Grandma tells them, “Go forward and don’t look back.”

And if our heartstrings are not torn enough, Buddy has to say good bye to his girlfriend Catherine. And as they are leaving Belfast Buddy tells his dad, “Dad, I want to marry her someday. But you know she is Catholic.” And in a scene that Brangan compares to To Kill a Mockingbird, Pa says,

“Son, I don’t care if she’s Catholic, Arab, Green or Blue. (But god knows, not a Jew). I am a good Protestant. You can marry whoever you want, Of course, as long as I don’t have to do anything about it. And besides, some of my best friends are Negroes.”

Branagh’s sanitized and ahistorical Belfast is a massive cover-up of the centuries-old British abuse of the Irish people and their many supporters among Protestant neo-colonial Irish fascists. Worse, it is a complete white-washing of the heroic reality of Catholic self-organization and resistance at the time that the entire world—except Branagh—was watching.

Someone should make a film about a Northern Ireland Protestant family standing with the Catholic led Civil Rights Movement and facing opprobrium and torture from the fascist Protestant mobs—but helping the struggle in the process. And yes, with the Catholic resistance at the center.

This could be modeled on the great film A Dry White Season, by Andre Brink. Set in South Africa in the 1970s during Apartheid, Ben du Toit, a privileged Afrikaner, (played by Donald Sutherland) begins breaking out of his racist cocoon when he tries to defend the rights of his gardener Gordon Ngulone (played by Winston Ntshona) who is protesting the police beatings of his son for partaking in anti-Apartheid protests. Later both Gordon and his son are murdered by the Apartheid police. Ben is a well-known, former cricket star, and expects to get answers and be respected by the police. Instead, he is interrogated and told to mind his own white business. Instead, Ben, step by step, becomes involved with the anti-Apartheid movement, allies with great Black leaders and teachers of the ANC, like the heroic Stanley Makhaya, played by the brilliant Zakes Mokae. In return for his conscience and courage Ben is murdered by the Afrikaner fascists, in particular, police Chief Captain Stolz, (played by Jurgen Prochnow.) In retaliation, Stanley murders Stolz, and the struggle for South African liberation moves forward. That film made it clear to the South African whites (and white people all over the world) that The System would exact a high price from the privileged for siding with the oppressed. A Dry White Season is not a “white hero” film but a film that said that yes, white peoples’ moral salvation can only come by joining the most oppressed and heroic liberation fighters and putting your body on the line.

Belfast teaches the opposite lesson. It argues, you should turn your back on the oppressed, raise superficial criticisms of the occupying Protestants and British, stay inside your pathetic nuclear family, and get the hell out of there when the opportunity arises. This is the portrayal of Kenneth Branagh’s actual life of which he should be profoundly ashamed. For Branagh to not have real Irish Catholic resistance leaders in the film puts this trash in the same garbage pail as Gone with the Wind. Eldridge Cleaver calling the moral question, said, “You are either part of the solution or part of the problem.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “He who accepts evil without protesting against it is really cooperating with it.” When confronted with these criticisms Branagh replied, “Frankly my dears, I don’t give a damn.”

It is only because we are in the midst of a great Counter-revolution in which imperialism is on the ideological ascendancy against the colonized masses that a film like Belfast could ever have been made. Today, Belfast may be nominated for an Oscar. But the only award this film deserves is a Thatcher.