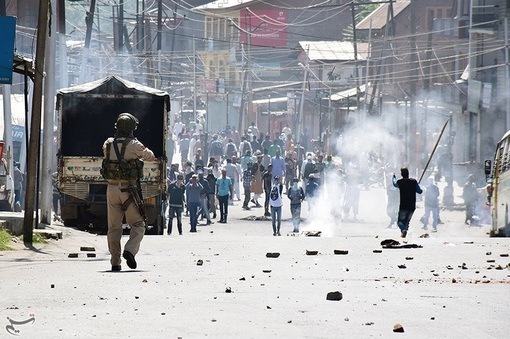

Photograph Source: Tasnim News Agency – CC BY 4.0

“In India today,” said an Indigenous activist I recently interviewed in the northeastern Indian state of Jharkhand, “everywhere is Kashmir.”

At first glance, this statement seems overblown, perhaps even outrageous. No other part of India is as much of a consolidated internal colony as Kashmir. For that matter, Palestine is one of the only other parts of the world that that can match or exceed Kashmir’s horrific past and renewed present of curfews, communication blackouts, transportation blockades, forced disappearances, and military and paramilitary brutality and bloodshed. (India’s ever-closer collaboration with Israel gives these parallels a particularly timely and unsettling significance.) In so many ways, nowhere is Kashmir but Kashmir itself.

And yet, the seeds of Kashmir’s never-ending misery are bearing poisonous fruit all across India. Animated by the interlocking forces of neoliberal capitalism and Hindu nationalism, the Indian state’s insatiable appetite for natural resources, ironclad commitment to elite-led economic growth, and gleeful deployment of grassroots fascist thugs and police, military, and paramilitary forces have fueled a mounting avalanche of tragedies across the country. Together, these priorities and capacities have caused an ongoing parade of stomach-churning mob lynchings; the harassment, imprisonment, and even assassinations of dissenters like Gladson Dungdung, Stan Swamy, and Gauri Lankesh; and the gagging, obstruction, and expulsion of civil society organizations like the Lawyers Collective and the Navsarjan Trust. If Kashmir’s condition can be described as a syndrome brought on by a shamelessly chauvinistic, mercilessly exploitative, and openly repressive state, its early and intermediate symptoms are increasingly visible everywhere.

The widespread nature of these symptoms should not, by any means, normalize Kashmir’s nightmare. If anything, it should stimulate solidarity-building between the state’s besieged population and the many others who find themselves more and more at the mercy of the Modi regime’s push for a Hindi-speaking Hindu Indian nation ruled by a handful of billionaires and their state collaborators. I dare suggest that I found traces of Kashmir on the streets and in the forests of Jharkhand. I offer the reflections below on my time there in the hopes that they will illustrate the need to confront combined weaponized, religiously sanctioned economic occupation as the defining political mode of the prevailing Indian state and its subcomponents.

The Investment Decimation

Billboards all over Ranchi, Jharkhand’s capital city, promote Momentum Jharkhand, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) state government’s tireless campaign to convert Jharkhand into “The Investment Destination.” This campaign exemplifies Jharkhand’s approach to economic growth by any means necessary since achieving statehood in 2000: successive Jharkhandi governments have signed hundreds of memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with public and private corporations across a range of industries, from steelmaking to agriculture to digital technology. At the inauguration of Momentum Jharkhand in 2017, reigning Chief Minister Raghubar Das signed no less than 209 MOUs worth Rs. 3 lakh crore or 42 billion USD, receiving New Delhi’s wholehearted approval and support in the process; one activist described Modi and Das as “brothers” for all intents and purposes.

From the Oracle Corporation to the Tata Group to hatemongering godman Baba Ramdev, Jharkhand’s investors have promised benefits galore to the residents of their host state, from jobs to educational institutions to technological innovation to support systems for small farmers and business people. In exchange, they have demanded uninhibited access to Jharkhandi land and the riches it contains; Jharkhand, after all, is home to 40% of India’s mineral wealth, including sizeable deposits of coal, bauxite, uranium, and gold. Jharkhand’s leaders have been more than happy to meet these demands: here, as elsewhere in Modi’s India, the irresistible spoils of economic occupation dissolve the notorious inefficiencies of bureaucratic and parliamentary institutions, forging public-private partnerships in which the actual public is a passive, if not entirely absent, actor.

The acquisition of land, however, has proven a crucial stumbling block to the state-backed corporatization of Jharkhand. Landforms the basis of traditional socioecological, sociopolitical, and sociocultural life for the state’s adivasis or Indigenous peoples, who account for 27% of Jharkhand’s population. “Our religion is our land,” explained renowned adivasi journalist and activist Dayamani Barla. “If it is taken away, nothing can live.” Between 2006 and 2010, Barla spearheaded a mass movement against the proposed establishment of two steel plants by global steel giant Arcelor-Mittal, which had signed an MOU with the Jharkhand government worth roughly 9.6 billion USD in 2005. Barla and her fellow protestors waged an effective public awareness campaign showing that the project, like so many other similar proposed and completed projects, would displace 30 to 40 villages, destroy adivasi sacred sites, key ecosystems, and prime agricultural land, and provide meagre compensation for these gross transgressions. In the course of her work, Barla received repeated death threats from middle-men subcontracted by the state and the company to secure the land in question, who assured her that her loved ones would not be able to identify her body once they were finished with her.

Barla and her compatriots prevailed in the face of these prospects of unspeakable violence; as of today, Arcelor-Mittal’s plans for Jharkhand remain in limbo. However, other corporations have made their marks all too clearly on Jharkhand’s landscape. “Every river in Northern Jharkhand has died, and every forest is black,” laments Barla. Furthermore, the Das government has only stepped up its efforts to facilitate the expropriation of land by public and private interests. In late 2016, it unilaterally passed a bill to amend the colonial-era Santhal Parganas Tenancy Act and Chota Nagpur Tenancy Act, which prevent the sale of adivasi land to non-adivasis. The abrogation of Article 35A of the Constitution, which limits the right to buy and own property to Kashmir’s permanent residents, echoes this bill in striking ways. Though it was forced to withdraw the bill in response to the public outcry that followed, the Jharkhandi state has attempted to divorce adivasis from their homelands by other, far more insidious means.

Death by Conversion

“Adivasis are not Hindus.” Virtually every activist, journalist, and intellectual I interviewed in Jharkhand drove home this point. It is a dangerously defiant response to the narrative spun by the BJP and, moreover, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the massive paramilitary volunteer organization that Arundhati Roy deems the “mothership” of the Hindu Right. The RSS has operated in the jungles of Jharkhand since at least the 1980s; in that time, it has done everything in its power to convince adivasis that their traditional beliefs and practices are squarely situated within its brand of casteist, patriarchal, materialistic Hinduism, despite countless scholarly texts and oral testimonies that indicate otherwise. RSS missionaries have offered numerous material incentives for conversion, from subsidies to the saving-and-investment schemes that have become the hallmarks of neoliberal “good governance” and “participatory development” across India and the Global South as a whole. Material enticements go hand-in-hand with symbolic warfare in Jharkhand’s public and private spheres: a prominent statue of legendary adivasi leader Birsa Munda was recently encircled with saffron flags, which also fly from every other rooftop in Ranchi and vie with red-and-white-striped adivasi sarna flags for dominion over the city’s street dividers and roundabouts. By reincarnating adivasis as Hindus, the RSS can defuse battles over land and forest rights before they can even begin, minimizing the costs associated with these battles: economic occupation in Modi’s India is a divine mandate underwritten by financial prudence.

To draw attention away from its own conversion programs, the RSS and its allies have attempted to stoke public paranoia around the boogeyman of forced conversions by the diverse Christian denominations that have been active in Jharkhand since 1845. In 2017, the Das government passed a hugely controversial anti-conversion bill that has served as a pretext for a heightened crackdown on Christian civil society actors. This is not to say, of course, that the state requires a sound legal basis for lashing out against religious dissenters and scapegoats: Jharkhand has witnessed 17 mob lynchings over the past three years, a good number of them carried out by gau rakshaks or cow protectors against Dalits, adivasis, and Muslims accused of slaughtering cattle or transporting them for slaughter. “It’s everyone against the Muslims,” remarked economist and activist Jean Drèze, encapsulating the Hindu Right’s deadly effectiveness at pitting the various victims of its policies against each other, in Jharkhand and beyond.

Fortress Jharkhand

As should be evident by now, legislated repression and extrajudicial violence work in tandem in Jharkhand. When middlemen and gau rakshaks prove insufficient to achieve its ends, the state can leverage its monopoly on legitimate violence by calling upon the myriad police, military, and paramilitary forces at its disposal. Securitization secures investments and conversions for Hindutva, Inc. at gunpoint by making non-compliance a blasphemous act of high treason, punishable by death. Ranchi’s glistening shopping centers teem with rifle-toting, khaki-suited personnel from the paramilitary Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), which has incidentally become synonymous with extrajudicial detention, disappearances, and executions in Kashmir. The Indian Army, meanwhile, maintains a cantonment or barracks area with a population of over 50,000 in Ramgarh, which just happens to home to several exceedingly rich mineral fields, including one of the region’s largest coalfields. Jharkhand’s security forces also drive dislocation, dispossession, and environmental degradation in and of themselves: for over thirty years, the Army’s has attempted to acquire 1,471 sq km of land in the Gumla and Latehar districts for the Neterhat Artillery Firing Range, which would permanently displace 100,000 adivasis and periodically displace another 150,000.

In the past 16 years, Jharkhandi police have opened fire upon adivasis protesting land acquisitions for development projects at least 16 times, proving their vital roles as day-to-day, ground-level enforcers of the state’s repressive extractivist agenda. Arbitrary arrests and staged “encounters” with alleged terrorists abound in Jharkhand: in 2015, the police gunned down 12 villagers with no criminal background whatsoever in the Latehar district, subsequently branding them Maoist insurgents; in early 2019, they arrested 20 young people in the Khunti district on the grounds that they shared seditious sentiments on social media. When heinous crimes do occur–such as the gang rape of five anti-human trafficking activists or the cold-blooded murders of anti-mining activist Suresh Oraon and journalist Amit Topno–the police either leap at the opportunity to frame pre-designated troublemakers or drag their feet when investigating the matters at hand. Under the circumstances of occupation, in which lawlessness is codified into law and smash-and-grab capitalism is the order of the day, calling upon the police to uphold law and order is a suicidal exercise in futility.

Battling Occupation Everywhere

Adivasi activists in Jharkhand and across India are alarmed by the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A for very concrete reasons. For a start, it could pave the way for the abrogation of Article 371, which provide vital special provisions for the states of Nagaland, Assam, Manipur, Andhra Pradesh, Sikkim and, by extension, their sizeable tribal populations.

Indians across the country, and people of conscience across the world, should be just as alarmed, even if not for the same exact reasons. India as a whole is under occupation by the hydra-headed forces of militarized, corporatized Hindustan. The blacked-out streets of Kashmir and the blackened forests of Jharkhand prove the cannibalistic nature of these forces. Instead of merely endangering the country’s overly idealized secular liberal democratic values, they threaten to devour virtually all of the human beings, ecosystems, and belief systems in their path, even those supposedly out of harm’s way. India is a sea of saffron at the moment, but, even in the handful of areas not controlled by the BJP and its National Democratic Alliance, the RSS is hard at work establishing shakhas or local branches; Arcelor-Mittal, Reliance, Tata, and Mahindra are hard at work setting up steel mills, supermarkets, and world cities; and local police, the CRPF, and the military are hard at work keeping the peace by normalizing war against the burgeoning ranks of the destitute. Bracketing Jharkhand and Kashmir as exceptional cases only provide time and space for these exceptions to become the rule; the most vulnerable members of Indian society will pay for this process of becoming with their lives even if it cannot achieve its genocidal goals.

India’s current sacred political economy of occupation is thus ontological in its orientation: it is an all-out attack on the very material and spiritual core of India’s being itself. And it can only be overcome in the final estimation by ontological means: by reclaiming the land itself from the sovereign political domain of the autocratic state and establishing autonomy, dignity, equity, justice, and resilience at the most basic levels of political life. Kashmiris across the ethno-religious spectrum have continued to courageously insist that their struggle cannot be reduced to a geopolitical tug-of-war between India and Pakistan and that they must be allowed to determine their own fate. Similarly, adivasis involved with the Pathalgadi movement that erupted across the states of Jharkhand, Odisha, and Chhattisgarh in early 2017 have refused to negotiate with the public authorities and private enterprises that threaten their very existence: they have erected massive stone slabs that list their constitutional and legal rights, using these declarations to keep out all hostile outsiders and construct their own banks, schools, and self-defence mechanisms. The brutal repression of both mobilizations possibly reflects the fear that they inspire in the combined powers they confront–fear of the emergence or re-emergence of other worlds and worldviews that, for all of their admitted limitations and contradictions, disrupt the relentless onward march of the bloodthirsty, privately incorporated Hindu nationalist juggernaut.

Everywhere in India today is Kashmir insofar as it is in the clutches or within the reach of neoliberal Hindu nationalist occupation. Everyone in India must now fight alongside Kashmiris–and Jharkhandi adivasis–to resist this occupation by any means necessary.