This year the Frankfurt Book Fair will take place between October 19 – 23. This account was written about the fair’s last gathering in 2021.

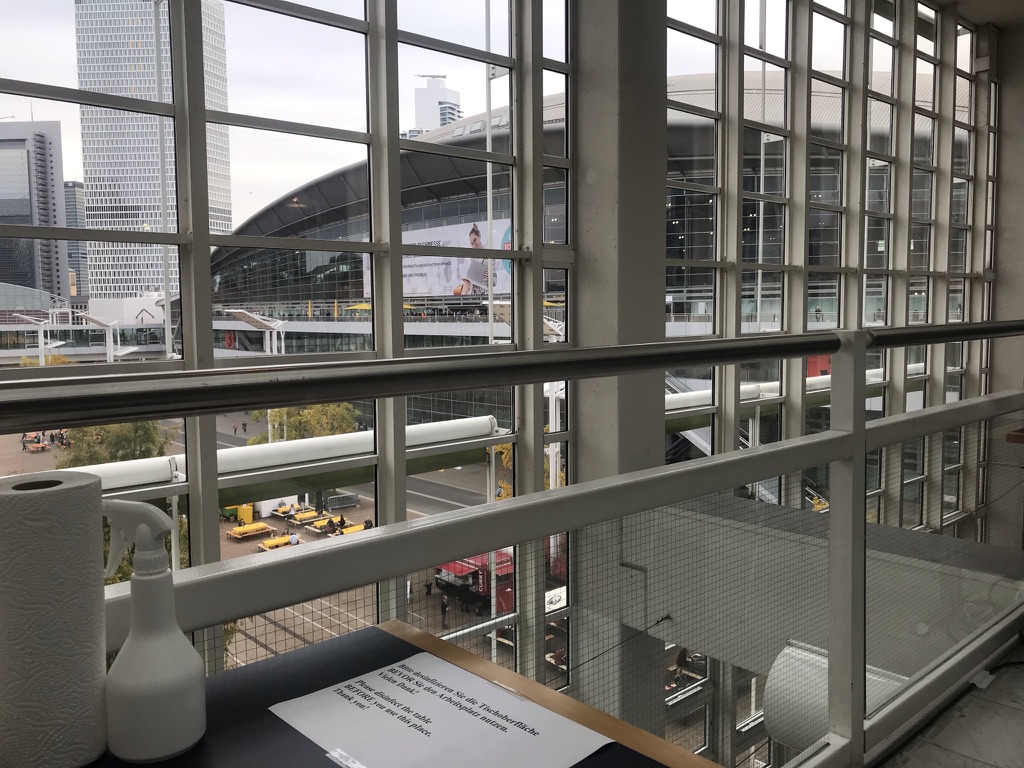

One of several halls at the Frankfurt Messe where the Book Fair unfolds over five days. Photo: Matthew Stevenson.

I know what you must be thinking: the Frankfurt Book Fair is a literary salon, complete with authors sipping sherry or padding around in Hush Puppy shoes. The reality is more mundane. Imagine an industrial tubing convention but on the display racks, instead of steel pipe, insert a few cook books, illustrated memoirs about gender confusion, and children’s books about lost dogs returned to their owners.

Translate all that into about thirty languages, spread the publications throughout six airplane-sized hangars, set up some booths with larger-than-life posters, and there you have the Frankfurt Book Fair.

Once the world expo of publishing, it now has less intellectual zing than that old newspaper box in your neighborhood that encourages you to “Leave a Book, Take a Book.”

“Between Milk and Yogurt”

Because I live not far from Frankfurt (down the tracks in Switzerland), I go every few years to the Book Fair, always with the expectation that I will meet editors, agents, and publishers interested in things that interest me (leaving aside my suicidal addiction to following the New York Jets).

With a spring in my step, I approach the “Frankfurter Buchmesse” with the hope that most of the display booths will have volumes about the Trans Siberian railway or perhaps a new book, with lots of maps, devoted to the politics of the 1848 Mexican-American War.

Two or three days later, I come away from my literary rounds reminded of New Yorker author Calvin Trillin’s description of best-sellers: books having a shelf life “somewhere between milk and yogurt.”

I leave with some new business cards in my wallet and promotional bookmarks and brochures in my briefcase, but otherwise I might well have spent my time wandering the aisles of a Bucharest supermarket, on the off chance that it would be stocking a new history about the politics of Transylvania.

Slow Trains Along the Rhine

Normally Frankfurt is a six-hour train ride from Geneva that involves a seamless change in Basel. Since the pandemic stuck, the trains in Europe have become a rolling mess.

A few weeks ago, when I went to Paris and Amiens, the two trains (one a TGV) were a combined four hours late. Recently when my son took the train from Zurich to Portugal (he avoids flying to spare the climate), it took him more than twelve hours to go between Madrid and Lisbon, which are otherwise about six hours apart by car.

Just to get to Basel on my way to Frankfurt I had to change trains in Bienne (a small Swiss city). In Basel, I discovered that the Deutsche Bahn ICE Express was out of service, requiring me to take a commuter train to Basel Badischer Bahnhof (across the Swiss-German border) and chase down another train heading north along the Rhine.

For the most part European tracks and rail cars (unlike Joe Biden’s dilapidated Amtrak) are in excellent condition. The European issue is that rail companies are largely confined to the national borders. Despite all the flag-waving about a European Union, passenger trains operate as if a Berlin Wall were present on most frontiers.

Of course, there are exceptions, such the Eurostar from London to Amsterdam and Paris, but on many train journeys across the continent I find myself trudging across national borders, as if a character in a John Le Carré spy novel, wondering what happened to the European ideal.

In Europe it’s the climate-busting subsidized discount airlines that are cheap; trains cost a fortune.

Red-lighting Frankfurt

Because I booked my tickets for the Book Fair at the last minute, I didn’t have many hotel choices near the exhibition halls, unless I wanted to spend €300 a night on a room in one of the international chains of convenience.

I ended up not far from the station, in a neighborhood that a Guardian travel article talked up as the center of “happening Frankfurt” (everything is relative).

I chose a hotel that, as best I could glean from the reviews, would react sympathetically when I tried to check in with my bicycle, which I drag along to be spared taxi and bus rides.

On arrival, biking from the station through a cold misty rain, I had no trouble finding the hotel’s neighborhood, but it did make me question the Guardian’s editorial judgement, as around my street there were tattoo and massage parlors, pinball arcades, cannabis salesmen, and what looked like an endless tailgate party on the sidewalks.

The Escher Exhibition Halls

To be there on time for the 9 a.m. opening (it’s in my Swiss blood), I biked to the sprawling fair grounds at 8:30 a.m. The weather had gone overnight from fog and rain to blustery and cold, and at a few intersections I had a hard time just turning my pedals into the headwinds.

I can only assume that the architect of Frankfurt Messe was a product of the 1960s and tripping on acid when he turned in his sketches for the interlocking exhibition halls.

Nothing is where it should be, and from the main entrance to the book displays I walked about a half hour down long empty hallways, occasionally riding on moving sidewalks, as if lost in the graphic art of M.C. Escher (all those random staircases).

English Unter Alles

I eventually found the English-language books in Hall 6. On the first floor there was a Chamber of Secrets, guarded by menacing receptionists, devoted to a “Literary Agents & Scouts Centre”. Access there required proof of a confirmed meeting, not to mention a vaccination and thorough hand washing.

In theory, the Frankfurt Book Fair is where world publishers gather to sell the rights to their books in other languages. Back when the fair had books and agents, I am sure a lot of subsidiary rights were sold in the “Scouts Centre”. But whenever I peered into this sanctum all I saw were rows of empty desks and booths, as though a spell had been cast on the book industry.

Downstairs at “English-language world and Asia” (taken from my Fair map) things were not much livelier. The first time I went to a Frankfurt Book Fair in 2001 I could hardly squeeze through the crowded aisles of the English-language world. This time (admittedly the pandemic is still raging in Europe), the hall felt like an abandoned shopping mall, yet another victim of online commerce.

The Publishing Big Five

Not one of the large U.S. or British publishers was present. Perhaps they had some talent scouts in disguise at the Fair, but none of them bothered to stock one of the Potemkin Villages (think of a stage set Hollywood bookstore) that are the trademark of the Fair.

Then I remembered that American book publishing has become an indifferent corporate oligarchy, in which about five global players control nearly all the books published each year.

The so-called Big Five of publishers are: Penguin/Random House, Hachette, Harper Collins, Simon and Schuster, and Macmillan. Collectively they control about 80 percent of the trade market—basically what you see on the shelves at Barnes & Noble.

It may be soon reduced to the Big Four, although for the moment the Justice Department is suing Penguin/Random House on anti-trust grounds to prevent it from acquiring Simon and Schuster. The government is arguing that the acquisition “would likely harm competition in the publishing industry”—itself a quaint notion.

Perhaps someday there will only one book publisher, and it can call itself OPEC (The Official Publishing Economic Council) or, if that’s taken, maybe the Texas Railroad Commission or Pravda (which by now must be in the public domain)?

In Frankfurt, none of these goliaths could be bothered (so much for the idea of competition) to send over their English-language fall list—all those thrillers written by Stephen King and Hillary Clinton (sic) or those gushy romances that Oprah has on her bedside reading table.

In about forty minutes on my first morning at the Fair, I had made my way through what Winston Churchill once called “the English-Speaking Peoples”.

Here’s a full summary of my meetings:

I met a writer/publisher from Texas who had recast the da Vinci code in the hills outside Austin; I unearthed a biography of Yugoslavia’s Marshal Tito (best understood as an Austrian archduke); I looked over the lists of some university presses (Racism Not Race…Undoing the Liberal World Order…When Bad Thinking Happens to Good People…); I spoke with a book review editor (it sounded like “pay per view”…); and I chatted up a Canadian publisher (“whatever books we sell, we sell in the U.S.”). Then I was done.

Emily Dickinson’s Book Fair

Walk anywhere in the Messe and someone will hand you a giveaway magazine that has the data on how many books were sold during the pandemic, and how everyone is reading more—in print, with eBooks, or on Audible.

Publishers sound like the parents of two-year olds who gush to their the friends about “how much Tiffany loves books”.

One sheet I was handed said book sales were up about 15 percent during the crisis, and that most people, when asked, had said they were “reading more”.

I am sure these figures are accurate. At the same time, I get the feeling that a lot of book publishing is hoping to imitate Netflix, and that the name of the game is to churn out blockbusters to reading clubs and book chains based on celebrity affiliation or endorsements.

The poet Emily Dickinson famously wrote:

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing Poetry –

Now I can imagine that in her Amherst bedroom she would be reduced to writing:

We’ve run the numbers, polled the Group

And checked with Gwynnie’s folks at Goop –

The gender plot, I’m told, is stellar,

’cause what we need is another best-seller.

Books are product, if not cattle, and Frankfurt is the stockyard.

The World, Not According to Garp

In the halls devoted to European and world books, at least there was some buzz on the floors.

The French companies had come with an army of rights salespersons, although— even more than the United States—France is self-absorbed, and I did wonder who would want to buy the reprint rights to an Emmanuel Macron biography in Asia. At least the coffee here was better than that in the American section.

Beyond the stands of European books, most of the booths looked as if they were peddling state-sponsored literature, further confirmation that much of publishing is a cross between agitation propaganda and annual reports.

The stand for Dubai looked less like a bookstore and more like the lobby of a five-star Gulf hotel; I was a little surprised not to find a few Bentleys parked in front.

At the Albanian stand, which felt like a magazine rack at a Tirana service station, I flipped through some of the maps, which had suggestions for road trips circa 2011.

Russia’s booth had a small stage with a TV screen on which (pre-recorded) authors could speak (and not go off-script). From what I could see on the surrounding shelves, the publishing industry there exists to talk up President Vladimir Putin, whose picture seemed to grace about half of the book jackets.

At the Afghanistan stall (it was hardly a booth), there was a hand-printed sign that read “No Books This Year”.

China’s booths were sprawling, expensive, and intellectually empty.

Emerging European countries such as Estonia, Bulgaria, and Latvia had sprightly (if largely forlorn) stands. Postcards with snappy Latvian literary quotations—“Our luck is accidental…”—did not prompt me to pack for Riga.

Deadly Regional Politics

I wandered into the Azerbaijan booth and picked up The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey: A Disputed Genocide (basically blaming the Armenians for living between the warring Turks and Russians in 1915). I then found myself in a long conversation with a diplomat who, while we spoke, fetched a map and explained to why Nagorno-Karabakh belonged to Azerbaijan.

Not only was there an Iranian stand (resembling a pistachio warehouse) but in another hall there was a booth devoted to the memory of the 176 victims on flight PS 752, the Ukrainian airliner shot down by the Revolutionary Guards over Tehran in January 2020.

I spoke with a victim’s relative, and he said the protesting group wanted both the black boxes and the truth about why the plane, carrying many Canadians of Iranian origin, was shot down just after taking off from Imam Khomeini International Airport.

He gave me some literature that said: “Ukrainian and Canadian teams faced zero cooperation by the Islamic Republic to clarify the details and find the truth about the downing.”

The victim’s relative chose not to dwell on the fact that the civil airliner was shot down hours after the Trump administration assassinated the Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani in a drone strike, which put Iran on high military alert and placed armed anti-aircraft missiles in the hands of Guards recruits. Not even in Frankfurt’s book aisles is Donald Trump held accountable.

Folding the Tents

I left the Book Fair after the second day, By then many of the publishers had left the Messe, leaving behind small hand-printed signs advising that visitors were welcome to take the promotional books left behind on the shelves.

Normally, only on the last day of the Fair are the display books surrendered to a horde on the prowl with shopping bags.

I didn’t go straight home but rode around Frankfurt on my bicycle. The city grew on me once I had escaped the red-light street parties and homeless encampments around the station.

On the surface, Frankfurt is a corporate park, with bland bank skyscrapers and insurance headquarters scattered around the city center.

During World War II Allied bombers demolished the medieval trading city that had existed for centuries on the banks of the River Main.

Here and there in downtown Frankfurt a few of the historic buildings survived the war or were subsequently rebuilt, although for the most part old Frankfurt is relegated to small district (a stage set for tourist meals) between the city hall and the rebuilt cathedral.

I headed toward the new Judengasse Museum, which was built over the fragmentary foundations of the Judengasse, the main street of Frankfurt’s Jewish ghetto that existed from the 15th to the 19th century (after which Jews were free to move elsewhere in the city).

The fragments were discovered in the 1980s when the street was being dug up, and rather than pushing ahead with a public utilities building, a museum rose in its place—to remember, with Pompeii-like foundations, the vanished civilization along the Judengasse.

Leaving Frankfurt: The Deportations

From the Judengasse—with strong winds at my back—I sailed into north Frankfurt, and along the river I found what is called the Memorial at the Frankfurt Grossmarkthalle, which in the 1940s was the deportation center for Frankfurt’s Jews on their way to extermination camps.

On the grounds where the Grossmarkthalle was located there is now the soaring headquarters of the European Central Bank, so some of the memorial is on bank property and not easy to visit (unless you go on a tour or are prepared to bail out the Greeks with some junk bonds).

The accessible part of the memorial is a series of quotes engraved into sidewalks and near the steps that led from the Grossmarkthalle to a railway bridge, where the trains to oblivion were loaded.

On one sidewalk there is a quotation from a man named Berthold Adler, who in 2005 recalled:

In the morning an SS-man — a German official from the party — came to our apartment and we packed our things. We were told what to take and what not to take. Then we had to go to the Markthalle, which is a long way off from where we lived. It was in the afternoon later [late afternoon].

Adler was one of the few who survived the deportations. Of Frankfurt’s Jewish population in May 1939 (about 14,000), the memorial at the Grossmarkthalle puts the number of victims—in camps around Minsk and Lodz—at 11,134.

Riding my bicycle back to the train station, to head home, the subject struck me as a good one for a book—why would a city as prosperous as Frankfurt want to devour its own citizens?—although the last place I would go to promote such a history would be the Frankfurt Book Fair.