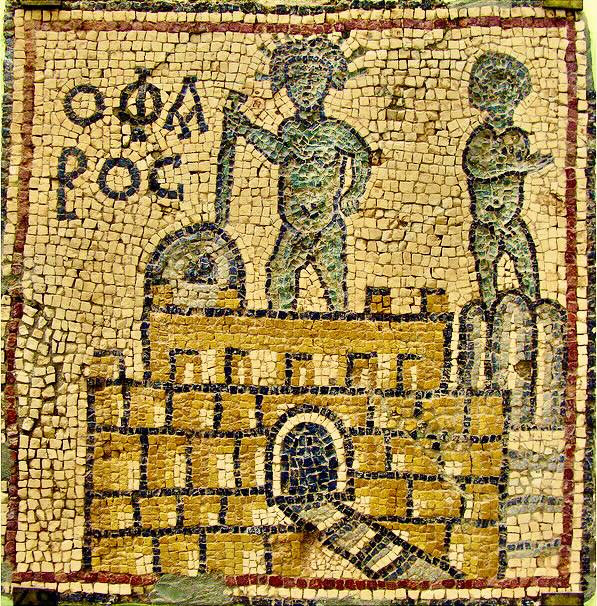

Mosaic of the Pharos (lighthouse) of Alexandria from Olbia Theodorias, Libya, about fourth century. Top left we read Ο ΦΑΡΟΣ (LIGHTHOUSE). Next, Sun god Helios (or Apollo) is holding the mechanism for the opening of the door of the lighthouse. Courtesy Wikipedia.

Prologue

Greece had two golden ages. The first took place after the Greeks defeated the Persians in early fifth century BCE. During the fifty years between the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, 479 – 431 BCE, Athens in particular shone with a flourishing and confident Greek culture: democracy and free speech and courts of law, the building of the Parthenon, the teaching of philosophy and science, employment of classical architecture, active theater, athletic games, and military strength. These signs of civilization, prosperity, and confidence were the pillars of a golden age.

The second golden age was the result of another Greek military victory over the Persians. This happened in the second half of the fourth century BCE when Alexander the Great, educated by Aristotle, conquered the Persian Empire and spread Hellenic culture throughout the world. The capital of Alexander’s empire was Alexandria, Egypt.

Alexander and Aristotle

Alexander, 356 – 323 BCE, was the son of King Philip II of Macedonia. Philip hired Aristotle to tutor his thirteen-year old son. Aristotle, 385 – 322 BCE, was a student of Plato and a great philosopher who invented what we call science.

For about seven years Aristotle taught Alexander Greek history, philosophy, politics, ethics, science and international relations, focusing on the Persian threat and the need for a united Greece to revenge the two Persian invasions of Greece in the early fifth century BCE.

Aristotle edited the Iliad of Homer for Alexander. His message to Alexander was this: unite Greece and stop the Persian danger. Homer was the passport Aristotle gave Alexander for entering the world of heroes, Hellenic virtues, and traditions. Greece needs to become one country, Aristotle kept saying to to Alexander.

The ideas of Aristotle found a fertile ground. Alexander became an intelligent and passionate lover of Hellenic culture and freedom.

In 336 BCE, a soldier assassinated King Philip II. Immediately, the twenty-year old Alexander became a king and launched his invasion and conquest of Persia. With Aristotle in mind, Alexander founded Alexandria in Egypt, making clear to his generals Alexandria was to be the Greek Aristotelian capital of his empire.

Alexander appointed one of his generals and close friends, Ptolemy, son of Lagos, 367 – 282 BCE, to be the governor of Egypt. When Alexander died suddenly in 323 BCE in Babylon, Iraq, Ptolemy consolidated his power in Egypt. In 305 BCE, he made himself King of Egypt and took the name Ptolemy I Soter (Savor). He started translating Alexander’s Aristotelian vision into reality.

Ptolemy was fortunate to have the assistance of Demetrios of Phaleron, a student of Aristotle who was also author of philosophical works. Demetrios convinced him to replicate Aristotle’s school in Athens in Alexandria, first of all, by building a Library and a Mouseion, Shrine of the Muses (university-institute for advanced studies). Ptolemy was also a student of Aristotle. He encouraged Demetrios to implement the Aristotelian proposal.

Mouseion and Library: Lighthouses of knowledge

At about 295 BCE, Ptolemy founded the Mouseion for the study and cultivation of Greek culture, the advancement of sciences, and poetry and literature. The methods and science of Aristotle took deep roots in Alexandria, becoming the intellectual infrastructure and the signature of a new society and civilization based on Hellenic culture, and science.

Ptolemy I died in 283 BCE. His successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphos (of Brotherly Love), 308 – 246, continued his father’s tradition. He lavished money and political support to the Mouseion and its staff, famous scientists, poets, and scholars recruited from all over the Greek world.

These academics did independent research and writing. They edited Homer and other ancient Greek philosophers, poets, historians and scientists. They advanced science and technology. They received handsome salaries and paid no taxes; they ate and lived in the Broucheion, which was part of the palace.

The Ptolemies also established a Library of about 500,000 volumes in the Broucheion section of the palace and a sister Library of probably 42,000 volumes in the temple of Zeus Serapis known as Serapeion / Serapeum.

One of the librarians, Kallimachos, compiled the Pinnakes, Πίνακες, a 120-volume catalogue of the collections of the Library. Staff of the Library combed Greece for manuscripts. Books found in ships coming to the harbor of Alexandria were copied for the Library.

The Mouseion and the Alexandrian Library were at the center of the Greek society in Alexandria and the Greek world. Alexandria surpassed Athens in scientific and technological achievements. It became the center of knowledge and civilization for Greece and the world.

Science and scholarship

The Greek kings of Alexander’s empire, especially the Ptolemies of Egypt, created the foundations for a rational commonwealth characterized by scientific exploration, state-funded research, the scholarly study of earlier Greek culture.

The scholars of Alexandria pioneered the techniques of scholarly research and painstaking study, which spread all over the civilized world. They continue to be the model for classical and scientific studies. This enlightenment lasted for more than five centuries: from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE until the second century.

However, late fourth, third and second centuries BCE were exceptionally fertile in Greek scientific genius. In late fourth century BCE, Euclid codified Greek mathematics in his masterpiece, The Elements. The third century BCE started with the awesome technical discovery of the mechanical toothed gears by Ktesibios of Alexandria. These mechanical gears were a form of advanced technology, that made possible the Antikythera Mechanism of the second century BCE as well as the Industrial Revolution of the seventeenth century.

Archimedes of Syracuse was a near contemporary of Ktesibios in the third century BCE. He worked and improved the gears Ktesibios invented. He wrote a book, On Spheres, in which he described the creation of a mechanical universe that, probably, resembled the Antikythera computer. That book, however, never made it to our time. Archimedes was such a great genius in mathematics and mechanics-engineering that, in a real sense, he set the foundations of modern science. Galileo and Newton became Galileo and Newton because they relied on the mathematical physics of Archimedes.

Eratosthenes of Kyrene (eastern region of Libya in north Africa) flourished in the third century BCE, too. He was such a versatile polymath, he was known as the Pentathlos (all-rounded). Eratosthenes made outstanding contributions to geography, chronology, and astronomy. He measured the distance between the Earth and the Sun and calculated the circumference of the Earth. He was also the chief librarian of the great Library of Alexandria.

Aristarchos of Samos, also of the third century BCE, invented the Heliocentric Theory of the Cosmos. He said the Sun god Helios, not the Gaia Earth, was at the center of the universe. This was a revolutionary advance in the science of astronomy and in human comprehension of how the world works. Archimedes noticed it and reported Aristarchos’ discovery in his work known as Psammites (Sand Reckoner), but it did not stay with him or most Greek scientists. They thought this was too much, overthrowing the millennia position of the Earth at the center of the Cosmos. Plato had been saying Gaia Earth was the oldest of the gods. Those who invented and created the Antikythera computer followed Aristarchos. Otherwise, that awesome discovery remained on the sidelines almost until the Catholic Polish monk Nicolaus Copernicus resurrected in the sixteenth century.

Apollonios of Perga, a contemporary to Archimedes, advanced Conics, a geometry of curves (ellipse, parabola, and hyperbola) resulting from the intersection of planes and cones.

In the second century BCE, Hipparchos, the greatest Greek astronomer in antiquity, set shop in Rhodes where he invented mathematical astronomy and left his fingertips on the Greek computer.

Antikythera Mechanism

I have written extensively on this astronomical computer of genius. Suffice it to say it captured the best in Greek science and technology. Very briefly, this computer confused and dazzled scientists. They were shocked with an ancient Greek astronomical machine that worked with gears, the first gears that made it from antiquity to Modern times.

For more than a century, Modern scientists confronted a metaphysical dilemma. They started investigating this geared machine by rejecting any notion that ancient Greeks had technology, much less advanced technology. And yet, in front of their eyes, there was a wrecked device working with advanced geared technology. The device, however, is at least 2,200 years old. Could the ancient Greeks have reached that high level of scientific technology? This puzzle paralyzed and confused scientists and researchers who either denied the computer’s scientific technology or thought the device was fake or non-Greek.

Derek de Solla Price, a British experimental physicist and historian of science, wrote in the 1959 issue of the Scientific American that he saw the Greek computer as “the venerable progenitor of all our present plethora of scientific hardware.” “It is a bit frightening,” Price admitted, “to know that just before the fall of their great civilization the ancient Greeks had come so close to our age, not only in their thought, but also in their scientific technology.”

Price became professor of the history of science at Yale University. He continued studying the fragments of the ancient computer at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Yes, he concluded, the Greek computer was a product of scientific technology, the likes of which did not appear in Europe before the eighteenth century.

In his insightful 1974 study of the Antikythera Mechanism, Gears from the Greeks, he found the Antikythera Mechanism was a “singular artifact…. The oldest existing relic of scientific technology, and the only complicated mechanical device we have from antiquity. [It] changes our ideas about the Greeks and makes visible a more continuous historical evolution of one of the most important main lines [of Greek science and technology] that lead to our civilization.”

One of Price’s principal discoveries was that in addition to its precisely interlocking gears, the Greek computer had a differential gear, the first ever created, which governed the entire mechanism. This was the gear that enabled the Antikythera computer to show the movements of the Sun and the Moon in “perfect consistency” with the phases of the Moon. “It must surely rank,” Price said of the differential gear, “as one of the greatest basic mechanical inventions of all time.” Price demonstrated that this technological advancement preceded the geared inventions of Leonardo da Vinci and other Renaissance inventors.

The Antikythera computer could accurately predict the eclipses of the Sun and the Moon as well as track the movements and position of the planets and major constellations. It benefited from the widespread tradition of techne (craftsmanship), the application of the sciences and crafts coming out of geometry purposefully applied in the design of machines for the benefit of all Greeks.

First, the Antikythera computer was a reliable religious, athletic, and agricultural calendar. It connected celestial phenomena to a calendar of the seasons, sowing and harvest, sacrifices to the gods, and the two and four-year cycles of religious and athletic celebrations in the Greek world. Because of its predictive function, it served astronomers, farmers, priests, and athletes.

It revealed the secrets of the stars by exhibiting the order of the whole heavens: it predicted the will of the gods.

The golden age of Greek science that produced the world’s first computer lasted from the late fourth century BCE till the second century of our era.

A Greek ecumene

Alexander’s successors spread Hellenic civilization throughout Asia and the Middle East while uniting Greece for the first time. Alexandria was the capital of this empire of learning.

Strabo, a Greek geographer whose life covered the violent transformation of the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire, 63 BCE to 23 CE, visited Alexandria. He was impressed by its wide streets crossing each other at right angles and suitable for horses and carriages. Alexandria, Strabo said, had “magnificent” public buildings and palaces that covered a fourth to a third of the city. Alexandria was also “full of dedications and sanctuaries.” The Gymnasium was the most beautiful building in Alexandria. The length of its porticoes was around 175 meters.

The Greek writer Theokritos of Syracuse, Sicily, was born at the end of the fourth century BCE. He knew Alexandria well. In his pastoral poetry, he praised Ptolemy II Philadelphos for his wealth, military might and wisdom. He reported Ptolemy II reigned over Egypt, rich in soil and towns, regions of Syria, Asia, Phoenicia, Arabia, Libya and Ethiopia. Ptolemy II was also the wealthiest king of the world.

Another Greek writer, Athenaios, who lived in the second century, quotes a book on Alexandria written by Kallixeimos of Rhodes. Kallixeimos, 210 – 150 BCE, described the great procession of 279 BCE. This was a procession of wealth and power the likes of which were rare in any time in the ancient world. The display of unfathomable riches was the work of Ptolemy II Philadelphos.

Alexandrians must have been astonished by the exotic animals, carriages full of representatives of the gods, 57,600 soldiers and 23,200 cavalry, and huge amounts of gold in statues, jewelry, and decorations.

Kallixeimos explained this unrivaled wealth in gold as a gift of the Nile, which “streamed” with gold and unlimited amounts of food. Kallixeimos also reports that in the procession he saw a mechanized statue standing up and sitting down on its own. It held a gold libation bowl from which it poured libations of milk. The automated statue held a garlanded staff like that of god Dionysos.

The statue operated on a cart decorated with a canopy and four gilded torches. We don’t know who mechanized the statue, but, in all likelihood, it was Ktesibios who lived in Alexandria during the reign of Ptolemy II.

Another report on the splendor of Alexandria under the Ptolemies comes from Herodias, a poet of mimes who flourished during the reign of Ptolemy II. Herodias bragged that all that the world produced existed in Egypt, and, most probably, Alexandria. He wrote:

“Wealth, wrestling grounds, power, peace, renown, spectacles, philosophers, money, young men, the precinct of the Brother-Sister gods [deified Ptolemy II and his sister-wife, Arsinoe], a good king, the Mouseion, wine, everything good one might want, women more in number – I swear by Kore [daughter of Demeter, Persephone] wife of Hades – than the sky boasts of stars, and in appearance like the goddesses who once rushed to be judged for their beauty by Paris.”

Pergamum also had a famous Library dedicated to research, science, inventions, and learning. King Attalos I, 241 – 197 BCE, lavished the Library with wealth and prestige. His dream was to make Pergamum a second Athens. He built the Pergamum Library next to a temple of Athena. He funded a replica of the Pheidias statue of Athena in the Parthenon for his Library. This made the Alexandrian Greeks uneasy.

During the reign of Eumenes II, 197 – 159 BCE, Egypt stopped exporting papyrus to Pergamum.

Papyrus was essential for book production. Pergamum used this unexpected crisis and invented a better alternative to papyrus.

This was a product from sheepskin known as pergamene from the name of Pergamum. Pergamene eventually came to be known as parchment, a technology that guaranteed hundreds of years of survival for books.

The Greeks in Alexandria, Pergamum, and, possibly, other Alexandrian kingdoms and Greek poleis produced modern-like science and institutions. Miroslav Ivanovich Rostovtzeff, a great Russian and American historian of Greece and Rome in the twentieth century, admired the achievements of the Greeks. Greek literature, art, and science, he said, remained Greek even after the death of Alexander the Great.

It’s wrong to call this a decadent or Hellenistic age, he said. On the contrary, he insisted, the Greek genius in the centuries after Alexander was just as creative as it had been in the centuries before Alexander. Greek civilization, in fact, spread over the world. City people spoke Greek. Cities in the post-Alexander Greek world, says Rostovtzeff, had a modern-like infrastructure of water supply, paved streets, healthy markers, schools, athletic stadia, libraries, outdoor stone theaters, racecourses, public buildings for local assemblies, and beautiful temples and altars for the worship of several gods.

Egypt under the Ptolemies, for example, had banks in all administrative districts and most villages. These royal banks lent money and regulated the currency and the economy. They invested funds and paid interest to depositors.

Ptolemy II put up unparalleled displays of wealth and funded unparalleled advancements in science and technology.

Throughout the Alexandrian world the educated classes read the same Greek books, went to the theater, and sent their children to the same wrestling schools and gymnasia. Children studied music, literature, and science – “a combination characteristic of Greece.” Finally, says Rostovtzeff, Greek paideia, education, was the badge of civilization. Reading Homer, Plato, and Sophocles and enjoying the comedies of Menander was essential to being a citizen of the Alexandrian Age. Failure in this Greek education was the equivalent to being a barbarian.

The Greeks did not force non-Greeks to become Greek, much less take up their civilization. The culture of the Greeks, says Rostovtzeff, “owed its worldwide recognition mainly to its perfection.”