This is the first part in series about travels in Saudi Arabia, along the line of the Hejaz railway.

Several years ago, at a Lawrence of Arabia exhibition at Magdalen College in Oxford, England, I came away with two convictions: I saw no political future for the Tory member of parliament Rory Stewart, who, despite speaking eloquently about T.E. Lawrence, had come and gone from a crowd of admirers without pausing to shake any hands (or very few); and, secondly, that I needed to do more reading and travels relating to Lawrence’s time in Arabia during World War I.

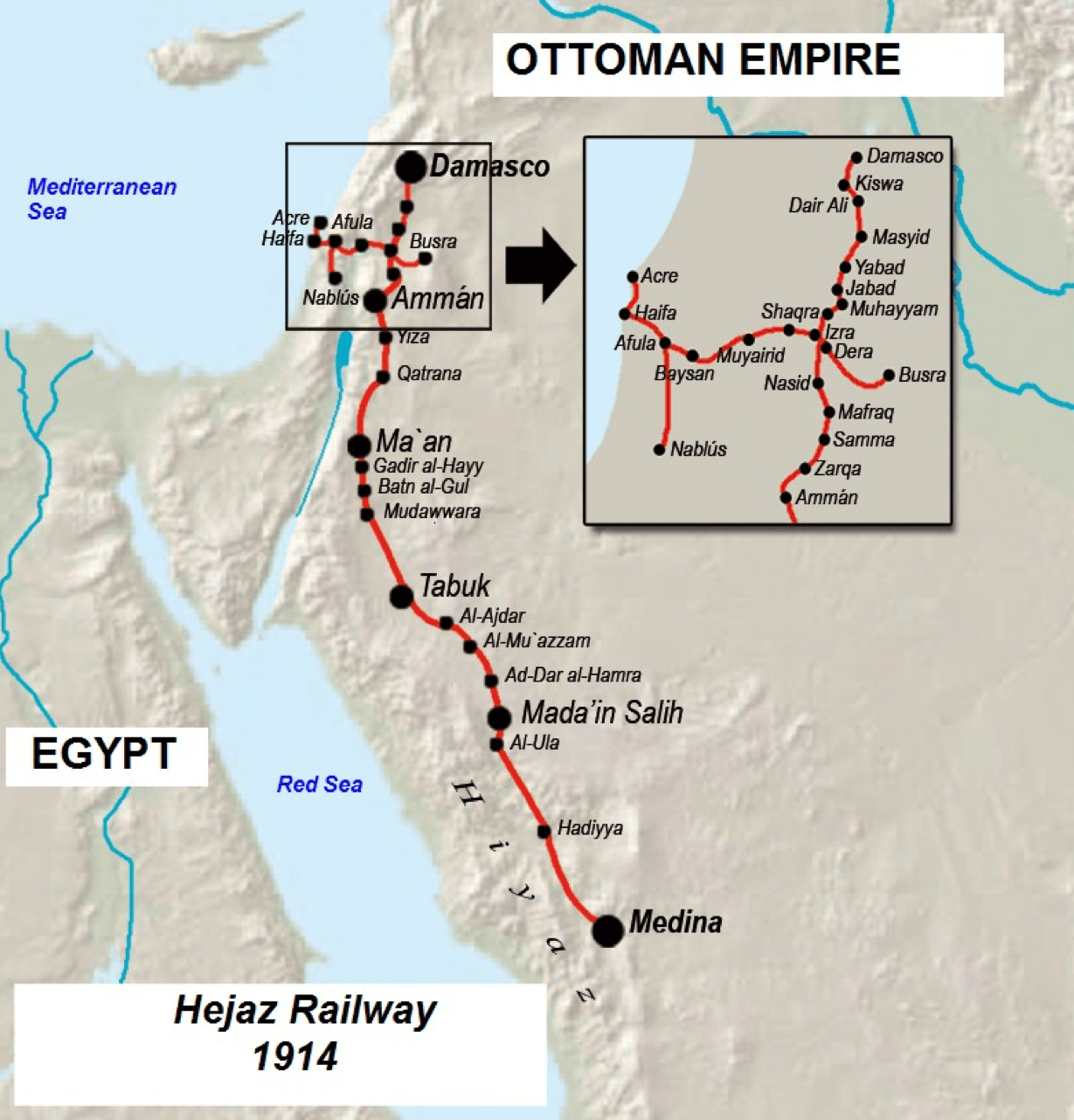

In the cabinets of the Magdalen library exhibition, I had spotted several books that interested me, notably Robert Graves’s Lawrence and the Arabs and Michael Korda’s Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia. As well, I spent time studying various maps on display of the Hejaz railway, wondering if I could ever follow its tracks into Saudi Arabia and its terminus in the holy city of Medina.

Together with my son Charles on our 2010 travels around Syria, I had seen its railway terminal in Damascus and a nearby museum (where the director showed us some of his 17,000 picture collection), and in the 1980s I had seen the outside of the Hejaz railway station in Amman.

After those station visits, the track bed went cold, and all I knew from maps was that the rail line crossed into the Saudi desert between Ma’an in Jordan and Tabuk in Saudi Arabia—across which Lawrence had led his band of Arab irregulars on their ride to attack Aqaba.

Leaving Oxford, I wondered what might remain of Lawrence’s railway in the wilds of the Saudi deserts.

The United States and Saudi Arabia: A One-Way Friendship

The problem I had with following the tracks of the Hejaz railway was that for American citizens it has been almost impossible to get a tourist visit for Saudi Arabia. By contrast, Saudis have an easier time getting U.S. visas.

I had tried a few years before, when flying to Kenya on Saudia Airlines. The airline allowed for a stopover in Jeddah, and I liked the idea of spending even twenty-four or forty-eight hours in the Red Sea city. But when I asked the airline counter and the Saudi consulate if I would have any luck securing a transit visa, I was told the process would be endless, and that in the end I would be turned down.

At the time I thought how little the American alliance with the Saudi kingdom (from 2015 – 2022 the U.S. gave the Saudis $54 billion in largely military aid) bought in return—at least for travelers curious to spend a few days along the Red Sea.

In the end, I had no choice when transiting through Jeddah but to remain cooped up in the airport, where I found the best place to overnight was on the floor of a transit lounge mosque.

Building Up the Tourist Accounts

I thought little more about Saudi Arabia or the Hejaz railway until my eye fell upon a newspaper article indicating that the new governing regime in Saudi Arabia (including those who had authorized the killing and dismemberment of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in the Istanbul consulate) were rethinking their approach to travel and tourism (beyond that of the haj to Mecca and Medina, which accounts for billions in revenue for the desert kingdom).

According to the article, in three or six months’ time it might even be possible to apply for a Saudi e-visa online and receive instant accreditation. I had my doubts about such informality, but e-visas are the rage in Southeast Asia, and maybe the Saudis would see the advantages of encouraging western tourists to cross its previously-closed borders.

It took me a while to follow up with my application, but in winter 2023, with two weeks free in my schedule, I had a go at the Saudi visa-on-arrival program.

I typed in my passport dates and numbers, uploaded a photograph, made a payment with a credit card, and expected to wait two weeks or even a month before hearing anything back. In the end, I took the view that I had not paid a lot for what I viewed as a Saudi lottery ticket. At least it had brightened my expectations on a dark January day.

What I didn’t expect was hearing back the next day that my e-visa had been approved, and that it was good for a year, in travel periods of ninety days.

Immediately, I began day-dreaming about a flight to Dammam (near Bahrain in eastern Saudi Arabia) and a train to Riyadh, or perhaps a bus from Amman, Jordan, to Al-Jouf, in the northern Saudi desert, and an overnight train to the capital. Saudi Arabia has been investing a lot in its trains, although it remains a car country.

I even wondered whether I could travel with my beloved folding bicycle, and use it to get around Saudi cities. But little in the way of international flights, buses, or trains seemed to go anywhere near the line of the Hejaz railway.

In Lawrence’s Camel Steps

In all it took about a week of brainstorming (brooding might be another word for my one-man deliberations), but I came up with the idea of a direct flight from Italy to Aqaba, not far from which there is a land crossing into Saudi Arabia. After watching some videos of its pinball traffic, I decided to leave my bicycle at home.

From there—although the details were missing from my dreams—I could go to Tabuk (a Hejaz railway city in northwestern Saudi Arabia) and follow the line south to Medina, one of the holy cities (the other being Mecca, which is off-limits to non-believers).

The Hejaz region is best imagined as the western strip of Saudi Arabia, running north to south along the Red Sea.

In Medina (assuming it would allow me inside its sacred gates), I could catch a new Chinese-built high-speed train to Jeddah, where, if my luck held, I could spend a few days beside the Red Sea and catch a one-way cruise ship for $211 that would take me to Yanbu, another port on the Red Sea, and up the Gulf of Suez to Ain Sokhna, one of the ports for Cairo.

What I loved about my plan was that all stops along my convoluted route were places that Lawrence writes about in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, especially Aqaba and Jeddah. If all worked as I hoped, I could read the Graves and Korda biographies and refresh my memories about the Lawrence legend. It was certainly worth trying.

Best-Laid Plans in Bergamo

I confess that the trip didn’t start as I would have hoped, in that I missed my flight to Aqaba from the small Italian city of Bergamo.

I had left Geneva before first light (at 5:39 a.m. to be exact) and in Bergamo had dropped off my Italian racing bike in a local shop that advertised custom paint jobs for old steel frames.

Getting to the Bergamo airport, however, took longer than I hoped—there were no taxis or Ubers—and at the airport, after I breathlessly sped through security, I rolled up at what I assumed was Gate 6 and took a seat by the window, surrounded by a gaggle of other travelers.

It was there that I discovered I had been denied a visa for Egypt, which would have meant I could not board the cruise ship for Cairo. Already my plans were falling apart, so I dragged out my computer to refile my visa application (the email turning down my request indicated a typo in my filing).

I worked feverishly on the application and kept on a eye on the departure gate, but after a while, when no one was moving toward a plane, I explored and saw that, without any public announcement, my flight had changed gates and departed from elsewhere in the airport. I was waiting with travelers heading to Marrakesh, which was not that day in my dreams.

Another Flight From Rome

As I had only paid $35 for my Bergamo airfare and allotted an extra day in Aqaba for just such a crisis, I could absorb the delay and financial loss but didn’t want to wait three days in Bergamo for the next flight to Jordan.

Ryanair, my discount carrier, was indifferent to my dilemma. Nor did “speaking with an agent” in the airport get me anything other than what I knew: that I was on my own.

I set up my computer in a corner of the Bergamo airport, and began an online search for other flights to Amman or Aqaba. After a while, checking nearby airports, I found a direct flight to Aqaba the next day from Rome that only cost $50.

In what felt like no time I was off from Bergamo to Rome, using a day of my Interrail pass. I ate dinner on the train, booked a hotel near Roma Termini, slept well in the warm night, and the next day found myself first in line at Rome Ciampino Airport (with no departure gate confusion this time) to board the flight to Aqaba.

Robert Graves and T.E. Lawrence

It was a four-hour flight to the Jordanian port city that shares the same coastline as Eilat, the Israeli beach resort, and Taba in Egypt. En route I was happy to begin the Graves biography.

My edition, published by Jonathan Cape in 1927, was elegant and cloth bound, and when turning its brittle pages it was easy for me to imagine Graves and Lawrence getting to know each other in postwar Oxford, when Lawrence was a fellow at All Soul’s and Graves was an undergraduate at Jesus College, from which Lawrence had graduated in 1910. Siegfried Sassoon, who knew Graves from the trenches of World War I, had introduced them.

In the Korda biography of Lawrence, there are several allusions to Graves “needing money” during his days in Oxford (the best-selling Good-Bye To All That was not published until 1929) and he writes that one reason Lawrence agreed to collaborate with the biography was so that his new friend could earn some income.

Lawrence would also have wanted Graves to correct some of the errors made in Lowell Thomas’s more sensational account, With Lawrence in Arabia, that could well have had the title A Few Days with Lawrence in Aqaba.

Aqaba Falls to Hollywood

Not long before my plane landed, we crossed into Israeli airspace, and all passengers were required to remain seated with their seat belts buckled (a footnote on Israeli politics five miles below us).

On our final approach we left the bleak, dry mountainous landscape of the Sinai peninsula and flew directly south over the town of Aqaba, which is divided between a working port and a beach resort.

The Graves biography devotes considerable attention to Lawrence’s 1917 military campaign to take the city from the Turks. At the time he was a junior liaison staff officer to Prince Feisal’s band of Arab fighters, and not under any orders to seize the strategic port. But he conceived of the attack from the “land side”, as his Arab detachment was moving north from around Yenbo to cut the Hejaz railway at various points (the line supplied the Turkish garrison in Medina).

Of that desert expedition, Graves writes: “One can well imagine Lawrence’s loneliness on this ride. He was no longer merely a British officer; his enthusiasm for the Revolt on its own account had cut him off from that. Nor was he a genuine Arab, as his tribelessness reminded him only too strongly. He hovered somewhere midway between the one thing and the other…”

Of Aqaba, Graves states:

The importance of Akaba was great. It was a constant threat to the British Army which had now reached the Gaza-Beersheba line and therefore left it behind the right flank: a small Turkish force from Akaba could do great damage and might even strike at Suez. But Lawrence saw that the Arabs needed Akaba as much and more than the British. If they took it, they could link up with the British Army at Beersheba, and show by their presence that they were a real national army, one to be reckoned with.

Just to get his forces in position to attack Aqaba, Lawrence had to lead them on a long, roundabout ride through the desert, and slip past Turkish sentries in the mountains outside Aqaba, so that the attack would come as a surprise.

The Real War Will Never Get Into the Movies

In the film Lawrence of Arabia, Lawrence leads the attacking Arabs on camels in a cavalry charge out of the hills and down into the town, where the Turkish forces were encamped, their guns pointing toward the sea, from which they expected an attack to come.

In the Hollywood movie, it is a charge of Light Brigade proportions, with the Turks wiped out to a man, although in reality the Turkish garrison surrendered rather than fight. Here’s how Graves describes the endgame:

They were, it was said, only three hundred men and had little food (the Arabs were in the same fix), but were prepared to resist strongly. This was found to be true. The Arabs sent a summons to surrender by white flag and by prisoners, but the Turks shot at both; at last a little Turkish conscript said that he could arrange it. He came back an hour later with a message that the Turks would surrender in two days if help did not come from Maan. This was folly; the tribesmen could not be held back much longer and it might mean the massacre of every Turk and loss to the Arabs too. So the conscript was given a sovereign and Lawrence and one or two more walked down close to the trenches with him again, sending him in to fetch an officer to parley with them. After some hesitation one came, and, when Lawrence explained that the Arab forces were growing and tempers were short, agreed to surrender next morning. The next morning fighting broke out again, hundreds of hill-men having come in that night knowing nothing of the arrangement; but [Sherif] Nasir [with Lawrence] stopped it and the surrender went off quietly after all. There were now no more Turks left between them and the sea. They raced on to Akaba in a driving sandstorm and splashed into the sea on July the sixth, exactly two months after setting out from Wejh.

Lawrence was among those who ended the campaign with a swim.

Next up: Aqaba and Wadi Rum.