“This a picture of the landscape. It’s daunting how solo it is. This is the exact wash/canyon we had to hike up to get to Martín.” Photo: Taylor Leigh

On February 16, a Guatemalan family contacted groups in southern Arizona about one of their family members who was lost in the Sonoran Desert after he crossed the U.S.-Mexico border. They had his exact coordinates, they had a photo of him, and they had a photo of his ID. Martín (not his real name) had been walking for about six days with a small group of people but couldn’t continue because of chest pain. Around 9 p.m., volunteers from the Tucson-based Frontera Aid Collective—a search and rescue and humanitarian aid group founded about two years ago—got involved. One of its members, Taylor Leigh, contacted BORSTAR, the U.S. Border Patrol’s rescue, search, and trauma unit. Leigh hoped this unit could rescue the stranded man.

According to Leigh, BORSTAR agent Hector Acuña told her she needed to contact the Guatemalan consulate because they couldn’t start a search until the consulate sent them the information. But the consulate was closed for the night. Another member of the Frontera Aid Collective, Scott Eichling, called BORSTAR again. Eichling said he wanted to make a report, and the dispatcher asked if this was about Martín. When Eichling said yes, according to the phone log, the dispatcher laughed and transferred him to Acuña, who told him they were “working on it.” When Eichling asked if they would start a search that night, Acuña said they would send someone in the morning. These were the first of more than 40 phone calls made by different people over two days. That night alone, humanitarian aid organizations called BORSTAR, the Three Points Police Department, the Pima County Sheriff’s Department, and the Tohono O’odham Police Department.

Meanwhile, the temperature was plummeting. It would get down to 27 degrees in the nearby town of Sasabe, and Martín was at a higher elevation in the Baboquivari mountain range, which runs north from the U.S.-Mexico boundary about 50 miles into the United States. The most prominent peak, a sacred site for the Tohono O’odham and a landmark for groups moving through the desert, stands at 7,730 feet. Martín’s location was frigid.

Unauthorized migrants have been traveling through this area, west of Nogales—an area that includes Arivaca, the Buenos Aires Wildlife Refuge, and the Tohono O’odham reservation—since the Border Patrol’s first deterrence operations in the mid-1990s. In Arizona this was Operation Safeguard (the younger sibling of the California-based Gatekeeper and the El Paso-based Hold-the-Line), and it brought more agents, walls, and technologies to Arizona border cities while forcing border crossers into the desert. In the 2000s the deterrence strategy expanded from the cities into more rural regions, such as the one around Sasabe. Post-9/11 budgets fueled initiatives like the Secure Fence Act and SBInet, building walls and filling the borderlands with enforcement technology—and pushing people into more treacherous landscapes like the Baboquivari mountain range. Now some of the border’s most traveled routes are through these desolate areas, thanks to the 30-foot walls around Sasabe (courtesy of the Trump administration) and the much more visible surveillance infrastructure, like the Integrated Fixed Towers (courtesy of the Obama administration).

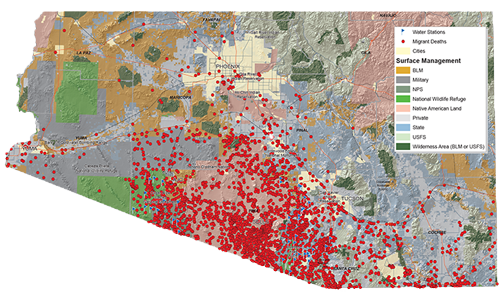

In other words, Martín was lost in a place where many people have died crossing the border. On a map that indicates with red dots where human remains have been found over the last 20 years, Martín was sitting in a sea of red.

The red dots on this map indicate where the remains of people have been found crossing the desert. You can find the maps here at the Humane Borders website.

According to a CBP information sheet, BORSTAR was created in 1998 to help address the “growing number of injuries to Border Patrol agents and migrant deaths along our nation’s borders.” Over the years the Border Patrol’s public relations have emphasized that BORSTAR saves lives. But according to a report titled Left to Die: Border Patrol, Search and Rescue, & the Crisis of Disappearance, published in 2021 by the humanitarian aid group No More Deaths, the Border Patrol’s nonresponse to Martín was not an anomaly. Researchers tracked hundreds of distress calls to the Derechos Humanos Missing Migrant Crisis Line, a nongovernmental initiative created to help families in search of lost loved ones. According to the data they compiled, 63 percent of the calls resulted in no confirmed rescue mobilization. For the 37 percent of the cases in which there was a rescue initiative, the searches were less rigorous than in those involving U.S. citizens. And in 27 percent of these cases, neither the person nor their remains were found. Historically, according to research by geographer Jill Williams, the Border Patrol’s emphasis on BORSTAR rescues seems disproportionate to the actual rescues. Yet BORSTAR’s annual budget, according to the Left to Die report, is $1.5 million, or .03 percent of the Border Patrol’s overall budget. Perhaps this is why BORSTAR is called a “publicity stunt” in an as of yet unpublished open letter to the Border Patrol written by members of the Tucson Samaritans and Frontera Aid Collective who were involved in the rescue.

After determining that the Border Patrol/BORSTAR was not going to do anything that night, and with doubts that anything would be done at all, a small group—including Leigh and Eichling—from the Tucson Samaritans and Frontera Aid Collective decided to search for Martín themselves. Around 10 p.m., they arrived at the Border Patrol checkpoint on Highway 286 (which goes to Sasabe) and talked to agents who were aware of the “Guatemalan man in the mountain,” but told them that the search was still not underway. After that, owing to many obstacles, including locked gates and private property, the volunteers did not arrive to Martín’s coordinates.

On February 17, the Tucson Samaritans and the FAC tried again along with another group that came from Phoenix called Abolitionists Search and Rescue, which also focuses on direct action around immigration. Although neither group reached Martín’s coordinates, they saw a Border Patrol helicopter fly to Martín’s location, only to leave quickly without landing. When Frontera Aid Collective volunteer Bryce Peterson later asked a Border Patrol agent why the helicopter didn’t land to rescue Martín, the agent said the person had to be “close to death.” Throughout this whole process, the rescue volunteers kept calling agencies, including the Border Patrol and BORSTAR (eight times that day, according to the call logs).

On February 18, a group set out again. Again they called the Border Patrol several times, and after driving as far as they could on unpaved roads toward Martín’s coordinates, the group came across a Border Patrol agent with the name patch J. Morales, who told them he was aware of the situation. The Guatemalan migrant, he said, “was just on the other side of that peak.” Morales said he had been told to stay put, and no other search was being conducted by Border Patrol.

The group started hiking up the mountain, and when they sensed they were close, they yelled his name. And then they listened. They thought they heard something. They were right. He was yelling back. They ran. And there he was, his jacket contrasting with the gold, green, and brown of the Sonoran Desert in the high mountains of the Baboquivari range. It was about 3 p.m., and the sun was beginning its descent into the late afternoon. Martín had no food. The gallon jug of water was almost empty. The rescue volunteers said he seemed despondent, exhausted. He didn’t get up. He was sitting on the ground. The group gave him water, food, and tended to his feet, which were in bad shape, cold and wet “to the core,” as if they had been enclosed in his boots for days.

They called his family, and on the speakerphone, a man—his brother? They didn’t know—started to cry with relief. Martín’s family told him, Nothing else matters. Don’t continue. Just come home. Just come back home. The money (a lot of money, they said, was paid for him to make the trip) didn’t matter.

As they went down the mountain, a four-hour journey, Martín was wobbly and in bad shape, but he perked up when the food and water got into his system. He began to talk about plants, his favorite plants from his home in Guatemala. He told Leigh that he had come to the United States to get work and that one of his brothers was already here. At the bottom of the hill, a Border Patrol agent named Brummel was waiting to arrest him. He, along with another agent, would take Martín’s vitals by the road with a flashlight, and then process and deport him to Nogales. According to the rescue group, the Border Patrol did nothing besides the helicopter flyby. I contacted the U.S. Border Patrol asking for their response or any comment on this situation with Martín and the actions of BORSTAR, but at the time of publication the agency still had not responded.

“I’ve been doing this for a couple years now, and I’ve gone on a lot of trips, sometimes in the summer, every weekend,” said volunteer David Zynda, who was one of the people present during the final rescue. “And this is the hardest thing, I think, I’ve ever done. … It doesn’t have to be this way. Not only did Border Patrol not go to him, but all these other search and rescue groups, who were much more trained than we were, didn’t go either, because Border Patrol assured them that they would be.”

A larger question loomed: If they hadn’t gone out and found Martín, because they thought BORSTAR was on it, would he have been left to die? Is BORSTAR more than a publicity stunt, as they put in the open letter to the Border Patrol, but in fact a menace to migrants’ lives?

Leigh said that before they arrived back to the road where the agent was, Martín told her that many people from other countries—from the United States, from Canada, from Mexico—come to his country, to enjoy his country, and it is “never a problem for them.” He wondered why it isn’t the same here. He wondered why he was treated this way. He said he didn’t understand why we make it so hard here.

This first appeared on Border Chronicles.