Stop the Pre-meditated state of Ohio murder of Keith Lamar on November 16, 2023

We must exonerate him and stop the death sentence

“Don’t forget that our time here is limited,

but we are walking through a place that is truly, truly magical”– Keith Lamar

Introduction

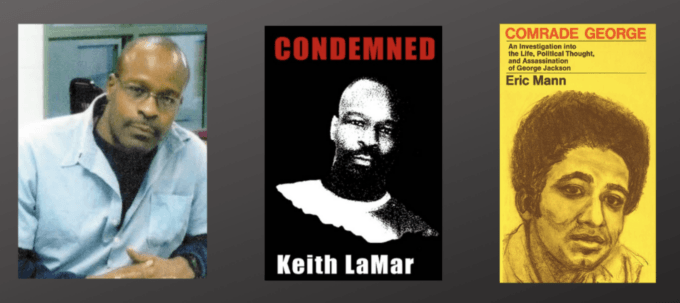

Several weeks ago, I got a forwarded email from my ecosocialist friend, Quincy Saul, about the case and life of Keith Lamar. Keith is a Black prisoner on death row convicted on perjured testimony, who is scheduled for state pre-mediated state murder on November 16, 2013—unless we are able to reverse the decision. Julian Lamb, our producer at our radio show/podcast, Voices from the Frontlines wrote an email to Keith Lamar.org (to which I urge each Counterpunch reader to subscribed) to have him on our show. Since then I have been working with Keith and Amy Gordiejew, his dedicated partner in the streets through letters, books, and two 1-hour conversations that have certainly transformed me. In our phone calls, I tell him I am reading his book, Condemned and he tells me that even in the hole, he is reading my book, Comrade George—An Investigation into the Life, Political Thought, and Assassination of George Jackson. For Keith and me, the written word, the spoken word, for us every word is a gift. We end each phone call and letter with “brother.”

What follows is our conversation broadcast January 24, 2023. The audio can be found on oicesfromtheFrontlines.com Listening to his voice is a gift.

Eric Mann: Good morning everyone. This is Eric Mann. I’m the host of Voices from the Frontlines, your national movement building show, Wake Up and Smell the Revolution. Today we are in conversation with the amazing Keith Lamar, who’s been in prison since 1989. And by 1993, when the prisoners rose up at the Lucasville prison in Ohio, he was absolutely falsely charged with killing other inmates as part of a complete frame up. He’s now on death row with, if we don’t stop it, a November 16th execution date by the murderous state of Ohio. Channing Martinez and Julian Lamb and I, along with Amy Gordiejew, spent an hour with Keith and then two or three hours before and afterwards to try to build a movement for this amazing man. So, you’ll hear my conversation. Please listen to all the requests, including financial support for his last appeal. With that, let’s . listen to this amazing brother. All support can be sent to KeithLamar.og

Hi Keith. How you doing?

Keith Lamar: I’m doing okay. Doing all right.

Eric Mann:Keith, this conversation is about you, but I did want to tell you that I was in prison for a year and a half for demonstrations against the war, spent more than 40 days in solitary confinement, and then three and a half more years’ probation, during which, at my probation officers’ whim, I would be put back in prison for two more years. I say this not in any way to compare our situations but for you to know I have deep empathy with your situation.

So, Keith, why don’t you tell us where you are in the present and future, where your mind is right now, and we can go back and do the backstory, but I think the present and future is where you’re living.

Keith Lamar: Yeah, that’d be right. As you may have learned from Amy, I’m scheduled to be executed in November. November the 16th, in fact. And we are right now trying to elevate the campaign, trying to bring awareness to my situation, trying to educate people about what happened to me in 1995, which is the year I was sentenced to death for crimes I didn’t commit. And I’ve been saying it from the beginning. One of the hardest things I’ve been trying to do, trying to get people to wrap their mind around the fact that you could be sentenced to death in this country and you innocent. And that the people that sentence you to death know you’re innocent.

Because they the ones who have held back the evidence to prove your innocence. And it’s almost as if what I’m trying to do in trying to convince people that I’m trying to convince them that the sun doesn’t rise in the morning. Because all of us have been, and including myself, part of the reason why I demanded the trial, because I believed in justice. All of us grew up here in America thinking “my country tis of thee” or saying the pledge of allegiance to the flag. I did that too. Even though I grew up in poverty, even though I grew up in ghetto, I was still equally indoctrinated. And so, in 1995, when the state wanted me to plead guilty to crimes I didn’t commit, I demanded a trial.

And that didn’t go how I expected, but that was a part of my education, something that I had to learn the hard way about reality in this country. So, I’m just going around, I’m educating people. I have a book club called Native Sons Literacy Project, which K started as a way to interact with “at risk youth,” not that I particularly like that name, but I go into the juvenile places in the beginning at least and talk to young people about the trap that have been set for them and try to get them to see and understand how to navigate. But part of that difficult assignment is trying to convince kids not to be kids. To think above your age and your [inaudible 00:05:43] and try to look into the future. But that’s what books allow you to do, fiction, allow you to imagine. And that’s one of the things that I was trying to do.

So, it has developed into a broader theme where I’m reading with college students, professors, so on and so forth. I recently taught several college classes and whatnot. And so that’s the thing that I’m doing, Eric. I’m going around, I’m educating people about the criminal justice system. And lo and behold, the people who put me here 30 years ago, they didn’t just do this to Keith Lamar. This is something that they did to a lot of people, a lot of Black people in particular. And all those cases are now coming to light. A guy here in Ohio named Elwood Jones was recently granted a new trial because the same people who put me here did the same thing to him. And a few weeks ago, another person who was in for 12 years ran into the same thing. And so now I’m not the lone voice in the wilderness telling the story about these prosecutors.

And these prosecutors in Cincinnati are really indicative of how the whole system work. So now I’m starting to gain some ground in telling this story. But in terms of my own particular case, there’s a documentary in the works, there’s a podcast in the works. There’s an album that we’ve been doing. And I’m having these conversations with people like yourself. And this is a day to day grind. A day-to-day thing. And I was telling Amy earlier, I was speaking to her earlier, I said, “Amy, even with everything that we’ve been doing…” And it’s a lot, and she’s been on the frontlines since the very beginning. My campaign started off with just she and I sitting in the business room imagining what could happen if we really, really tried to do something like this with our life.

Eric Mann: I heard you said it started with you and Amy. I started the Strategy Center in a little underground office with two desks and no windows. The two of you are great organizers, you have built the most impressive national and international network. I’m in awe. I just wanted to read a couple of sentences, Keith, if that’s okay, to give my own short version of your story:

An uprising in1993 where you did nothing

Place in solitary confinement and death row

Convicted by fabricated evidence

Paid Jailhouse informants

Prosecutors peddling false narratives that had made up and got paid jailhouse informants to regurgitate

Withholding of evidence that could prove your case

Suppressed confession of actual perpetrator

Trial in remote Ohio community

All white Jury, Black jurors dismissed

Welcome to Amerika, Land of the Free.

Keith Lamar: Yeah, that’s basically a blueprint. It happens to people every day in this country. Poor people, particularly Brown and Black people of course. But yes, it’s just something that happens that’s prevalent in this so-called criminal justice system. Definitely.

Eric Mann: Keith, tell me how your day goes every day. What’s your routine? How do you go through it? What do you think about? What do you do?

Keith Lamar: Well, I’m in prison. Obviously, there’s no [inaudible 00:09:31]. At any moment without notice it can get very loud in here where we won’t even be able to hear each other. So, during those times, it’s hard to write. It’s hard to read. And so, I try to go to sleep by at nine o’clock. So, I could wake up at two, three o’clock in the morning when it’s very quiet. That’s when I do most of my thinking and reading and my writing. And of course, I’m on the phone probably four or five hours a day. I’m talking to people, having conversations. Amy also is a school teacher, so she works.

I wrote a book, Condemned, that tells the true story of my life. I wrote that book in eight months. It took Amy transcribing the book over the phone because we had attempted to write some pages, sent them through the mail, but those pages never made it to her house.

So, I just would recite the pages over the phone and she would transcribe them every morning before she went to work as a school teacher. And that’s how the book, in eight months, the book Condemned was finished. But yeah, I get up early in the morning, man. I try to make the most out of those few quiet hours that I’m allotted and try to get as much work as I possibly can. But I have to meditate, I have to work out, I have to stick to this real rigid routine in order just to stay alive. But getting back to what I was saying earlier, I told Amy, “Even with everything we’ve done, Amy, doesn’t necessarily mean that we are going to prevail.” I say that not to be discouraging because I’m not doing this or I’m not… Mainly the way I live my life is to bend things to my will.”

This is what I’m living. And so that’s what I call everything, getting up in the morning, doing everything, that’s living to me. And I was thanking her just for being such a good friend to me in my life. Because a lot of people think, especially her, I’m sure she would take it personal if this thing doesn’t turn out the way we hope. But I just want her to know and remind her at different points along the way that, “Listen, just having a friend like you is hitting the lottery.” Just meeting somebody like you on this earth, it’s like winning something really, really big. And I think that’s something that we have to do and acknowledge amongst ourselves with each other. Because we’re fighting something that’s really, really bigger than us. It’s a monstrosity. It’s the American government. And other people are engaged in similar battles and we have to stop sometimes in the heat of things to acknowledge each other’s presence and our contributions.

Eric Mann: Well, I think gratitude is so important. And you both hit the lottery—finding each other. You both did.

Tell us a little about your workout. When I was in prison, I read Soledad Brother by George Jackson, and I’m going to get you a copy of my book, Comrade George: An Investigation into the Life, Political Thought, and Assassination of George Jackson. But he used to talk about doing 1000 fingertip pushups in his cell. I did about 250 but not fingertips. But he pushed me every night. Tell us about working out in your cell.

Keith Lamar: George Jackson has been a big influence in my life as well. I’ve never got up to 1000 fingertip pushups, but I have done thousands of pushups in a single session before. I’m 53 years old now. I’m 34 years inside. So, I’m not working out as vigorously as I was when I was in my twenties. Not even so much focus on the strength so much as the peace. I do yoga, I have yoga, and so I’m stretching because I’m sleeping on this bed, this concrete slab for the past three decades.

And so, it has brought a lot of damage to my body. And so, I’m just stretching and trying to… Let’s just say I do get my life back and I am one day walking on the other side of this situation. I like to be able to enjoy whatever life that is left for me. And so, I take care of myself as best I can. I run every day. I try to eat as best as I possibly can. So, I’m being honest, I’m not as disciplined as I probably should be in that area because you don’t have a lot of pleasures in here. And so once or twice a year, my family, they send to me a food parcel. There’s a lot of things in here that a 50-year-old man shouldn’t be eating. But I do it all in moderation and just try to squeeze some joy out of my day.

Eric Mann: Sure. When I was in prison I learned yoga, meditation, and vegetarianism. I know the exercise is also a form of meditation. Channing asked about your political development. Prison is often a university of revolution and there’s a lot of brilliant prisoners in there, a lot of books, a lot of intellectual life. What was your development like, even into the present, who are some of the political thinkers who have shaped your philosophy and your outlook?

Keith Lamar: Well, George Jackson, as I mentioned, had a big impact on me. Angela Davis, of course Assata Shakur, definitely Malcolm X, Ruben ‘Hurricane’ Carter, Staughton Lynd, a historian here in Ohio who recently passed away came into my life in 1996 or so and he was a big part of my political maturation. He the one who talked to me about working class because he was involved with the unions and the work to keep the mills and factories open. He was the one who really taught me about free market capitalism, about the industrialization and how that coincide with mass incarceration. So, I was able to talk to professors, historians to make those links and to find a trajectory of that development because mass incarceration didn’t happen in a vacuum. This is an effect of something. But you don’t know that if you’ve been labeled a criminal and been housed in one of these places, you don’t really know the history because everything is so immediate and urgent inside of here.

And so, one of the side effects of being put in solitary confinement is that I have the time without having to… Because when you in population, it’s difficult to study because you have to work. They force you to work and it’s just rife with all these gangs and whatnot. And you have to worry about protecting yourself.

A lot of people don’t understand that prisons are very violent places and a lot of your energy is spent on trying to just protect yourself. Out of solitary confinement, it’s not always a benefit. It has challenges that doesn’t present in population—sensory deprivation and all those things. But I turned my room, myself, into a classroom. Filled it with good books instead of pain. And I’ve read extensively from people who have been in similar situations, Primo Levi, Victor Franco, people who were in the Jewish Holocaust and concentration camps. And so, all those books out here, all those people are here with me. I’m not in the cell by myself alone. I have friends who are alive and friends who are dead. So, all these people have contributed to my education.

Eric Mann: Yeah. In 1965, I was at the SDS March on Washington and I heard Robert Moses say that we have to link the war in Vietnam with segregation in Mississippi and mass bombing in Vietnam. And Staughton Lynd said that we have to put our bodies on the line. We have to make a physical sacrifice. So, I know Staughton back from 65 and I know his contribution as an historian. So, you’re lucky because you are able to see your life in an historical context. Some of the prisoners can’t see their lives that way. So, I’m sure that your cell looks like a library.

Keith Lamar: Staughton lived close so he was able to come to the prison on a fairly regular basis. And we were extremely close for a quarter of a century that he was in my life. And I spoke at his funeral. Alice Lynd was here visiting me about a month ago and we commiserated on the contributions that Stauhgton made not just to my life, but to everybody’s lives that he touched. But it’s lucky, man. I was lucky, Eric, I’m a high school dropout, dropped out of high school in 10th grade. But most of my friends are college professors, professional musicians, people who have achieved themselves in one line or another. And these are the people who make up my army.

Eric Mann: Well, Keith, we have a Strategy and Soul bookstore in Los Angeles and inside we have our own bookstore—called Strategy and Soul Books. t’s on the corner of King and Crenshaw in South Central Los Angeles. And we have this thing that I’m the main organizer of the books. So, it’s called the 100 most important books that any organizer must read in a lifetime. At least we give people a lifetime. So, we’re going to add your book, Condemned to that list. I already ordered some and Amy sent them some. So, we’re going to have a section of your book and your work in our bookstore, Keith.

Keith Lamar: Oh, that’s great. Yeah. Thanks so much. I know this book was just recently released in Spanish about a week or so ago. I think it’ll be translated in French end of next month and then in Germany. And so, George Jackson in his book, Soledad Brother, he has a line in there. He said, “Before this is over with, the whole world is going know about me.” That they wouldn’t just kill him and his life would be over. And we are still talking about George Jackson today. And it is not that I have that as an aspiration, but he inspired me to think outside of this little room that I’m in.

We were in Berlin in November. We won the Innovation Award, spoke in front of all these accomplished people who are engaged in trying to abolish the death penalty worldwide. And we were able to share the music that we did on the free first album. And not long after that, my name and campaign was scribed on the Berlin Wall. And not to say that it stayed there because people paint over these things, but for a moment, my name, it may be still there, but I had pictures of it and everything. So, George Jackson was with me.

Eric Mann: I’m interested in reading your book because the thing about George Jackson’s book Soledad Brother is it’s mainly letters to his mother, to his friends, and its beautiful literature. So, I’m interested in reading your writing, Keith, as I’m already hearing your spoken word.

Keith Lamar: Richard Wright was also a big influence. His story, Black Boy, his autobiography, I read that book every day, every morning when I was first sentenced to death. And I didn’t really have a television, radio or any of those distractions. And so, I read that book, not just as a… I read the story first and I went back and started over. I read it probably 10 times in my life I was paying attention to the punctuations, the syntax, how he formed the synthesis, and how he selected the different experiences in his life to bring home a certain point and whatnot.

And so, writing is just an extension of who you are, where you are. It’s difficult because you can never get close to what you really, truly want to say. I guess the best writers, Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, they came close. Martin Luther King was a terrific writer as well. And I have all his work here with me as well. And so yeah, I’m in good stead in terms of being able to draw inspiration. Writing is really a torturous process for me because I don’t have the structure of the foundation that one might receive from a university. But like George Jackson, I taught myself how to write here in this little cell. And it’s not really writing so much as it is fighting. I’m not really trying to become a literary person. I’m trying to express my existence, to say, “Keith Lamar came through here.” And so that book, that was so difficult to write. It ends with “This isn’t just a book you have in your hands. It is my life. I’m innocent.”

Voice from prison phone system “You have one-minute remaining. This call is from a correction facility and is subject to monitoring and recording.”

Eric Mann: I heard you loud and clear that “It’s not so much writing as much as it is fighting.” So, in my interpretation you were saying you are fighting as resistance but also to defend your existence.”

Keith Lamar: Yeah, my existence. Yeah.

Eric Mann: What do you think about legacy?

Keith Lamar: Yes, Legacy. I think about that a lot. Legacy is something that will happen whether you are conscious of it or not. You are leaving the legacy behind. A lot of those people in the civil rights movement, we talk about Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, so on and so forth. But it was thousands, billions of nameless, faceless people whose name we don’t know, we’ll never know. And those people by being there, have a legacy. Their family knew who they were and what they were doing. And so, I’m aware of what I am creating what I will ultimately leave behind. And I’m conscious of trying to inject as much righteousness into my walk as I possibly can.

I did a lot of things, especially when I was younger, that required the forgiveness of others. In ignorance, I sold drugs in my community. And part of the reason why I wanted to create Native Sons and go back and help the young people who were on the same trajectory as I was when I was 12, 13 years old, it’s an acknowledgement of the harm I’ve caused because that’s also a part of your legacy.

And 15 years ago, when I googled my name, it was basically all bad. “Keith Lamar is a scumbag.” But that of course was being written by people who were trying to kill me. And they had me in prison for allegedly killing a woman. I’m in prison for murder. I pled guilty and I acknowledged the wrong that happened in my situation, in my life, but I didn’t kill a woman. And the reason why they made that “mistake” is that when people Google your name, that they would turn off from your situation because you were in prison for killing the child or killing a female. And it’s subtle, but it’s really, really impactful in terms of how people engage with your story. And so, we fought to get them to change that, to get the correct crimes for which I was initially convicted, absurd as that may sound. Because I accept responsibility for what I’ve done and where I am wrong in my life, but you have to tell the truth. Come correct. And you have to fight for that.

But over these past 10, 15 years or so, we’ve overwhelmed that narrative. And so, when you look up my name now, you see all the things that we’ve been doing, that I’ve been doing with the help of my friends and supporters. You have to go dig really deep to find something that these people, the state has negative to say about me. And that’s my legacy, not what they say. Because I tell young people that you might not be writing your story, but somebody is writing it and they just call it a biography. And somebody’s writing your story whether you are conscious of it or not.

These things that you are doing now are being compiled. And it might not seem like anything because you are a child. But these things, when they were trying to get me to cop out to crime that took place in a 1993 prison uprising, they went back to when I was 13 years old and brought up the fact that I tried to steal some blue jeans out of JC Penney. I was 13. And so, these things really, really, really, really matter. And that’s what I think that childhood is about is if you from the ghettos, you racking up this thing that would be used against you at some future date. And so, you have to really, really be careful if you are a Black person, particularly if you are a Black male navigating the inner cities of this capitalist country. So, talk about all those things. Those are very, very important to me.

Eric Mann: Yeah, Keith, of course, we do work in LA. We finally got the school board to get rid of the so-called crime of willful defiance, which was nothing more than Black boys being Black boys. Singing, dancing, jumping up, being loud when a teacher said something to you, talking back, that’s it. And they would expel them from school for so-called willful defiance. And of course, when it’s a white kid, they say “Boys will be boys.” The system treats white kids totally the opposite of Black children. Look, when I was a kid, I shoplifted and the guy said, “Why’d you do a thing like that? You should be ashamed of yourself.” That’s it. No police, no arrest, just “go home because I was white. So, you Keith, shoplift at a JC Penney when you’re 13. They’re already trying to hang the first step in criminalizing you for a lifetime for what could have been, ‘Don’t even come in this store again.”

Keith Lamar: Yeah. I tell you, Eric, I grew up in this little small community called the Village. People who were part of the great migration trying to come north to get jobs in the north and factories. And it was a community that comprised 100 houses. People owned their houses. My grandfather paid $12,000 for his little house, and that was the homestead for my family. And this was real dignified. Our community, working class community. People worked hard. They were loyal. And I can go into people houses at dinnertime and eat dinner, so on, and so forth. But we moved away from there, and I came into the inner city and I was about 10 years old. I went to school and man, those kids let me have it, man. “You’re the most ugliest person on the planet,” according to them. My hair was nappy. My clothes were dirty. I still have a complex about it. I’m talking about it traumatized me, man. And we were poor, so we couldn’t afford all those name brands. But see, that’s the trick that this country play on you. They give you this image on what value is.

So, everybody’s is called to reach for these little trinkets that this society hold out, but everybody isn’t obviously on the same playing field where it’s possible to achieve these things, to acquire these things. So, I became a thief because feeling like a piece of shit was all had already been established. One of the lessons that I learned coming out of my childhood that what you had was more important than who you were, who you are.

I had a Mercedes Benz. I had a Rolex watch. I had all those things, but I was still unhappy. When I came to prison and I met some guys who mentored me, who helped me to understand where I went wrong, I came to realize I was in the prison before I even came to prison. My self-concept was deeply distorted by this whole materialistic way of navigating with life. And so that was one of the first things I had to really, really correct. But I still struggle with that. That 12-year-old boy is still alive in me. And even as I’m trying to do this work, even as I’m trying to focus on my legacy, he’s still trying to prove that he has value. It just something that I have to be conscious of as I find my way forward.

Eric Mann: You’re listening to the wonderful Keith Lamar who’s more alive inside the bars than most people are outside and much more alive than the people who put him behind bars, the liars and the cheaters and the cops and the screws and the white settler state. Prisoners, as you know, are very philosophical. I learned yoga in prison. I learned meditation in prison. We did yoga together. We fasted. We became vegetarians. Many of my teachers were the Black brothers who were very good to me, who had looked out for me, by the way. I don’t want to glorify prison, but people don’t realize the high level of philosophical and ethical life that prisoners are trying to figure out.

Keith Lamar: Yeah. I agree with you, Eric. No one was sitting in junior high school, elementary school saying, “When I grow up, I want to be a criminal. I want to be a convict. I want to spend three decades in prison.” This is nobody’s dream. So, a lot of guys are really, really focused on trying to figure out where things went wrong. That’s one of the things when I came here, I gravitated towards these people who were engaged in that work. These guys were my first psychiatrists, people who tried to help me heal some of the mental or the psychic harm, trauma that my childhood created in me. And so, these guys saved me. And I’m not happy that I spent 34 years in prison.

But I was on a visit yesterday with one of my childhood friends, and I was telling him the same thing. And what you were saying about people on the street being not as developed as someone who has been engaged in cultivating themselves as I have over the past 30 years. And that’s true. Some of the people that I’ve grown up with, they come visit me here and there, and I’m shocked sometimes and sad that they are still standing in the exact same place they were 30 years ago. I don’t judge them for that. I understand. But when I think about my own life, and I have to put it on the scale. Because I was shocked on the case that initially brought me to prison. I’ve crawled into this pissy hallway in the projects where I lived, and I lost so much blood I passed out. My brother who was with me at the time called the ambulance, and I woke up in the hospital, but for all intents and purposes, I died right there as an 18-year-old.

So, I don’t sit here thinking like, “Woe its me.” Because really technically my life could have ended then. And so, I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about that, but I do spend a lot of time thinking about, “Damn, what would have happened to me had I remained on that side of reality, the person that I was?” I was laughing with Amy earlier because they offered me a deal and I said, “Amy, in the parallel world, that Keith Lamar who took the deal, I’m wondering how he’s doing. I wonder what kind of person he is right now.” And we laugh because that’s a made-up thing. Had I taken the easy way out in my life, I would be a totally different person than I am now. My life is hard. It continues to be the case, but I’m glad I had the strength and presence of mind to say yes to my life as opposed to being swindled into taking this deal to forfeit my opportunity to achieve myself. And so, it’s a hell of a journey, man. That’s it, what experience has taught me. Yeah.

Eric Mann: Obviously, Keith, I’m just getting to know you and I want to get to know you better if you would. You’re a deeply introspective person. I always tell people as organizers, “Do you have the guts to look in the mirror?” A lot of times I don’t like what I see, but that’s my journey. I like a lot. I don’t like a lot. But every day I’m working on the things that I don’t like about myself or the things that I see I do over and over again. And I go back into my soul and say, “Where is this coming from?” And I’m doing some good work to go down there and find it. And sometimes I want to beat it up, but I have found that loving it often works better.

Keith Lamar: Yeah. Eric, I’m the same way, man. It’s patterns. And these patterns persist no matter how far we move away from them. We created this thing, this construct called “time” to give us a sense of movement. But certain parts of ourselves is still standing in 1969, 1975, these pivotal moments where we were imprinted with these things about who we are. “This is who you are, Eric.” And we had those things, those things are literally set in stone.

I know who I am. I know where I’ve been, what I’ve done, things I’ve seen. And a lot of it is not good. But it’s a scale though. And it’s not like a blindfold with the Lady of Justice. I don’t understand that, but I’m looking at it squarely. I’m looking at it as squarely as I can, and I’m trying to live up to my potential every day. And sometimes I’m successful, sometimes I’m not. But thankfully, I wake up the next day and I get 24 more hours to try to get it right. And I’m trying. That’s the only thing that you can really do. You constantly trying to overcome your former self that we all seem to be (get AUDIO for this conclusion)

Eric Mann You know Keith, most of the time when we are talking I forget this is being recorded for a radio show/podcast. For me, the show is you and me talking and other people are lucky enough to listen in. It’s just you and me could be just sitting in your cell talking and we record it and that’s the show.

Keith Lamar: I want to give people a visual description of where I am right now. I’m sitting in this little closet on the toilet by the door, trying to keep a strong connection to the Wi-Fi signal here. This is something new here in prisons. All these corporations have flooded into these places to exploit poor people, whether they have Wi-Fi, emails and so on and so forth. But these things come at great expense, and they very seldom, if ever actually work the way that they are supposed to work. The only thing that works here, Eric, is that cash register works efficiently. So that’s where all the professionals work. Everything falls through the cracks, but not the money. Man, they real efficient on getting that money off the books, man. Yeah.

Eric Mann: So, Keith, obviously this conversation and relationship is transforming my life for the better. And we will have you back on Voices very soon. But for now, Keith, listen, what are your last words to people? And how can our audience help you. Because, on Voices from the Frontlines, we tell our listers, “You have to beyond ‘listener sponsored radio’ to organizer involved radio. Once you know you are obligated to act.”

Keith Lamar: I’m someone who lives every day with the awareness of my mortality. I’m on death row. I was speaking to one of my young friends, a young lady, 17 years old, the other day, and I told her “When you were born into this world and discovered that people had wings and flew across the sky, you would accept that and you would wait patiently for your wings and for your lessons on flying.” And by the time you were 12 years old, you would be flying and it wouldn’t be an amazing thing. It’s only amazing because you can’t do it. Dinosaurs are only amazing because they’re no longer here. And one day we’ll no longer be here. And maybe then somebody would say, “You are amazing.” But the fact of the matter, as I pointed out to this young woman, is that you flew here to see me.

And yet the only thing that you recall in your journey is the long lines and the frustrations and all these things. One of my favorite poets, Kahlil Gibran said, “If you keep your heart and wonder of the daily miracles in your life, then your pain will seem no less wondrous than your joy.” And I just think that people need to find a way to be inspired, to be encouraged, because we are only here for a short period of time. We walking through this mysterious world, man, it’s billions of years old, over 4 billion years old. We are right now on that planet where dinosaurs once roamed. The ancient Egyptians were here. And we are here now. And you don’t have to do something where the whole world is going to know about it, but just walk with your awareness that your life is magical and the fact that you are here, that you are breathing, that you are living in 2023.

All these people passed away during the pandemic, millions of people. But you didn’t. You are still here. We are still here. And that’s really, really important. And we still had the opportunity to stop and think about how magical it is to be alive. That’s something that I try to remind myself of every day and not just focus on the pain, but focus on the daily miracles. And that helps, man, that helps a great deal. And so that’s what I want to leave people with. Don’t forget that our time here is limited, but we are walking through a place that is truly, truly magical.

Eric Mann: Well, Keith, that is very beautiful, and I’m sure Kahlil Gibran would be very proud of you.

Taking Action for Keith Lamar Now!

For those of you who want to really get serious about death penalty fights and prisoner’s fights, you can work with the strategy center info@thestrategycenter.org. And I’m going to ask Amy Gordiejew, why don’t you tell us all the different ways we can help Keith and the movement that you’re doing?

Amy Gordiejew: The first thing folks can do is go to keithlamar.org and learn about him and get an idea of all of the things he’s involved in. One of the things that I’d ask everyone to do is just scroll to the bottom of any page and add their name to the email database so we can stay in touch. We’re sending out monthly newsletters as we fight these last months in lead up to the proposed execution date as we’re steering this thing around and turning it away from that outcome. And so that’s one way we can stay in touch.

There’s a petition that we would love for people to not just sign it, but also to send it out into their networks because it only takes one little spark for that to go viral. And the more people we have on it, the more other folks with influence will pay attention and want to see what is happening here. So, it’s really important. We are really deeply involved in fundraising right now because Keith desperately needs research in his legal defense. We just recently learned we have access to the database of Evidence NOW. And to compel the courts to give him a retrial, we have to be able to convince them of all the things that were withheld, and we need to be able to afford that support to go in there and find all of that Evidence NOW. So, we’re in a real, real critical period.

Eric Mann: Amy, you have a lawyer who’s going to help, but this is going to cost lots of money. If people want to contribute, how do they specifically contribute the money? It’s very important just to let them know.

Amy Gordiejew: If they go to keithlamar.org/donate, there are many easy ways. You can give by credit card. You can do it through CashApp, Venmo, PayPal. It has a mailing address. And we are also a 501(c)(3) organization. So we’re nonprofit and anybody who wishes to make a sizable contribution and get a letter from us, we’re happy to provide that. So that’s something. So, the petition, donation, getting themselves added our email list where you will get regular updates.

They can order Condemned on the website or go to keithlamar.org/condemned. And then following us on social media. We are on Instagram and Facebook @justiceforkeithlamar and Twitter @freekeithlamar.