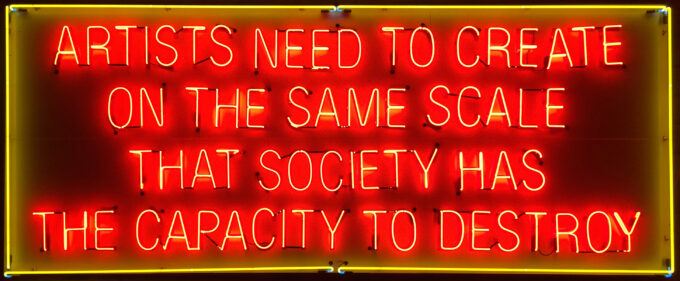

Lauren Bon & Metabolic Studio, Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale that Society Has the Capacity to Destroy, 2022, Neon.

Right now, when the art world, like the larger culture within which it is embedded, is stressed beyond belief, this is the right moment for radical innovation. For what history shows sometimes is that traumatic crises open up the possibilities for dramatic change. For a long time, theorists have classified contemporary art in terms of mutually exclusive binary oppositions. Early modernists set the advanced avant-garde against aesthetically reactionary Salon painting. Clement Greenberg presented self-critical modernism versus the uncritical kitsch of mass culture. Rosalind Krauss and her Octoberists opposed politically progressive post-modernists to their aesthetically reactionary contemporaries. And of course, other theorists proposed various other oppositions. Over time the examples have changed, but the governing principle always remains the same: there is the good progressive work and the opposite, the bad conformist art. But now it’s possible to drastically change that way of thinking.

The Brooklyn Rail, a free monthly journal founded in October 2000, publishes ten issues per year, both 20,000 in hard copy and online with 3 million in readership worldwide. It includes art reviews, interviews with artists and also coverage of books, music, dance, poetry, theater, and politics. Phong H. Bui, the publisher and artistic-director, who has up-to-date curated nearly 100 exhibitions since The Rail‘s conception, has undertaken, at the arrival of the Trump Presidency 2016, a series of exhibitions since under the slogan Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale that Society Has the Capacity to Destroy, a neon work by Lauren Bon, which can be used as a title or a subtitle. For example, Occupy Mana: Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale that Society Has the Capacity to Destroy at Mana Contemporary, New Jersey, and Occupy Colby: Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale that Society Has the Capacity to Destroy in 2017, or Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale that Society Has the Capacity to Destroy: Mare Nostrum as collateral project, co-curated with Francesca Pietropaolo, at Venice Biennale in 2019. And starting in May 2022, working with Cal McKeever, he organized seven exhibitions in New York City collectively entitled Singing in Unison: Artists Need to Create On the Same Scale That Society Has the Capacity to Destroy.

These exhibitions each contains a lot of art in dense hangings. And they are accompanied by public programing, including poetry readings, panel discussions, music and dance performances. In the recent seventh show alone, September 23–December 17, 2022, in a 16,000 square feet space at Industry City, Sunset Park, Brooklyn was the work of 69 artists, mostly large paintings, sculptures, or installations; some of them were by senior famous figures, but others are relatively obscure or even unknown artists. There is a checklist at the door, but no labels, so to see who did what, you need to look for yourself. There have been over 14,000 visitors, a vast audience for a group show of contemporary art in Brooklyn. As The Rail website explains, these hangings embody “a democratic vista, represent(ing) a symphony of individual creations that celebrates culture for all.” The underlying and consistent theme throughout these exhibitions is the visual dialogues between works of art, made by trained artists, and those are self-taught, from the very well-known to the lesser-known, for example, Julian Schnabel, Sean Scully, Liliane Tomasko, Ugo Rondinone, David Reed, Katherine Bradford, and Kady JLKR are installed alongside Thornton Dial, Purvis Young, Jared Owens, James Drinkwater, and Uman; there even are self-portraits made by 1st grade students from Queens. In all of these exhibitions, instead of providing the context or curatorial framework for the viewers, including wall texts and labels for the works, its purpose seems to do the opposite: giving the viewers the experience of looking at the work of art on their own volition; surrendering to their receptivity without textual or any other forms of support.

Retrospectives like the Carnegie Internationals or the Whitney Biennales usually have a selection principle. Here, however, you see very many of the options for contemporary American visual art. The Brooklyn Rail is a big tent, committed to showing as much as possible of the enormous variety of contemporary art. Will you like all that you see? Truly not! What of this art then matters most? To answer this question, you need to look for yourself, for the pleasure of seeing the uniqueness of one work that corresponds to another is entirely dependent on self-discovery. In every case, each work of art, be it abstract or representational, can certainly relate to one another through varieties of formal issues, including images, colors, textures, materials, etc., etc., which at times can be seen directly overt alongside to each other in close proximity, other times indirectly subtle from afar.

This philosophy of general democratic organizing principle is similarly applied to the reviewing and interviews in pages of the journal, which are exceedingly wide ranging. The December 2022-January 23 issue has 152 pages in the print edition, in addition to over 60 WebEx articles, more materials, I suspect, than anyone apart from the editors is likely to have time to read. The aim is to provide as comprehensive as possible a picture of art making, and other cultural productions in New York, and beyond, today. The guiding model here is given by the American art historian, Irving Sandler (1925-2018), who in his books covered a large number of the best-known American artists from the Abstract Expressionists to the present. His announced goal, achieved with success, was to provide an impartial, comprehensive record. Unlike Greenberg or Krauss (and most of their successors), he didn’t make a moralizing distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ art. And, in addition, since the first program aired on March 17, 2020 at the start of the Covid epidemic the Rail has organized daily Zoom, known as New Social Environment Lunchtime Conversation series. Now with over 700 episodes completed, these programs (which are available on-line) have alone reached a viewership of more than two million. Here, again, the aim is to provide a comprehensive report on the present cultural scene. Comparing himself to the director of a symphony, Bui has said that his contributors, “who . . . are musicians with distinct sounds” are each “treated as equally important.” The Rail is thus radically rethinking and revising the nature of art criticism and the contemporary art exhibition.

The critical implications of this practice are highly suggestive and so deserve spelling out. The amount of information provided by The Rail– and the quantity of art on display at the Rail exhibitions is astonishing. In these shows, as is not the case in most museum or gallery surveys, you get something like a full view of our art world practice. There is, however, one important but historically distant precedent, the Salons held in the Louvre on the eve of the French Revolution. These exhibitions attract a great deal of scholarly attention because the free mingling of classes making free aesthetic judgments anticipated the political debates of the French Revolution. Like The Rail-shows, these visually busy art displays aspired to show all the contemporary art of interest. Because there was so much to look at, the need for written guides inspired the birth of art criticism. The first recognizable critic Denis Diderot devoted more than 350 pages of close commentary to the Salon of 1767. The contemporary French paintings presented were very different from the works in The Rail’s shows, and the style of Diderot’s commentary unlike that of our critics. But the hanging arrangement of these exhibitions are not so very different from those of the French old regime. Then, as now, the public needed to judge a great quantity of contemporary art.

Working quite independently from the Rail, in two recent books about what we call ‘wild art’, art from outside the art world, Joachim Pissarro and I have developed an aesthetic theory supporting (in part) this radically original way of thinking. With the presentation of hundreds of examples and a full historical and philosophical textual apparatus we critique traditional aesthetic theory. But discussion of the affinities of our account to the concerns of The Rail’s publication and exhibitions is another story, for another occasion.

Note:

As a reviewer and one of the 37 editors-at-large I am involved with The Rail. The publication is freely accessible online. On the Venice show see my: https://hyperallergic.com/510079/reconciling-secular-art-in-sacred-spaces/ For the New York shows, see https://industrycity.com/visit/explore/brooklyn-rail/. My account borrows from Charles Duncan, “Democratic Visages. Portrait Drawings and Meditation Paintings of Phong Bui, “ Symphonies and Meditations , exhibition catalogue (New York, 2022). See also, Diderot on Art, Volume II: The Salon of 1767 (1995). Joachim Pissarro and I are the authors of Wild Art (2013) and Aesthetics of the Margins/ The Margins of Aesthetics: Wild Art Explained (2018).