Photo by Adam Szuscik

Republicans are arguing about resurrecting an Independent State Legislature Theory (ISLT) derived from language within the dysfunctional Articles of Confederation Constitution. This is the Constitution that stopped the colonies from forming a functional central government until our current Constitution replaced it.

Harvard University law professor Noah Feldman labels this theory as a “hyper-literal interpretation” of Article I, section 4 of the U.S. Constitution: “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.” North Carolina Republican State Legislators initiated the Moore v. Harper case before the Supreme Court (SCOTUS) to argue that a state legislature can violate its state’s Constitution in congressional elections.

If SCOTUS were to uphold ISLT, a state legislature could overturn any federal election’s popular vote if they believed it was critically unfair. They could ignore their state’s supreme court order to adhere to the recorded vote. In a close electoral count, Feldman points out that “a rogue state legislature could determine the outcome of a presidential election” by reassigning electors to the losing presidential candidate.

In the Florida State University Law Review, Hayward H. Smith detailed how some Justices constructed ISLT from Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, which says state legislatures direct the manner of appointing presidential electors under this Article.

He argues that using a textualist interpretation, “the founding fathers’ original understanding of Article II did not identify independent powers to state legislatures. Ironically the lead promoter of ISLT is Justice Clarence Thomas, who embraces a textual interpretation of the Constitution. Smith’s paper shows that textualism reveals strong indications that the founding generation conceived Article II legislatures in the normal sense “as creatures born of, and constrained by, their state constitutions.”

I’ve previously explained how this obscure theory was floated as a strategy to overturn Biden’s 2020 presidential election. However, because SCOTUS has never rejected the theory, it appeared earlier in the two 2000 Bush vs. Gore cases that resulted in sanctioning Bush’s total vote without a recount.

Of which Justice Thomas is the only one remaining on the bench, three justices opined that state legislatures “must remain free from incorrect state court statutory interpretations.” Consequently, SCOTUS rejected the Florida Supreme Court’s ruling for recounting the votes in certain counties to arrive at an accurate outcome of the 2000 presidential election. And the votes went to Bush, not Gore, allowing George W. Bush to become president.

In the Moore v. Harper case, Thomas will try to get the SCOTUS to adopt his prior opinion from the Bush case. He wrote that state legislatures, in directing the appointment “of presidential electors under Article II, Section 1, they must remain free from state constitutional limitations.”

Other than refuting the Independent State Legislature theory, which will not happen with the reactionary justices in the majority, the court will most likely rule on two critical conditions that limit a legislature’s ability to wield ISLT.

The first is whether Governors are included in the definition of “legislature.” If they are, a Governor could stop the transfer of electoral votes to the losing candidates, assuming the legislature does not overrule their veto. The second critical feature is that a state legislature’s decisions are subject to their state’s interpretation as being legal. Suppose SCOTUS decides, in the Moore v. Harper case, that legislatures can ignore their supreme court’s decisions. In that case, legislatures dominated by one party could overturn the popular vote to allow their losing presidential candidate to receive the electoral votes.

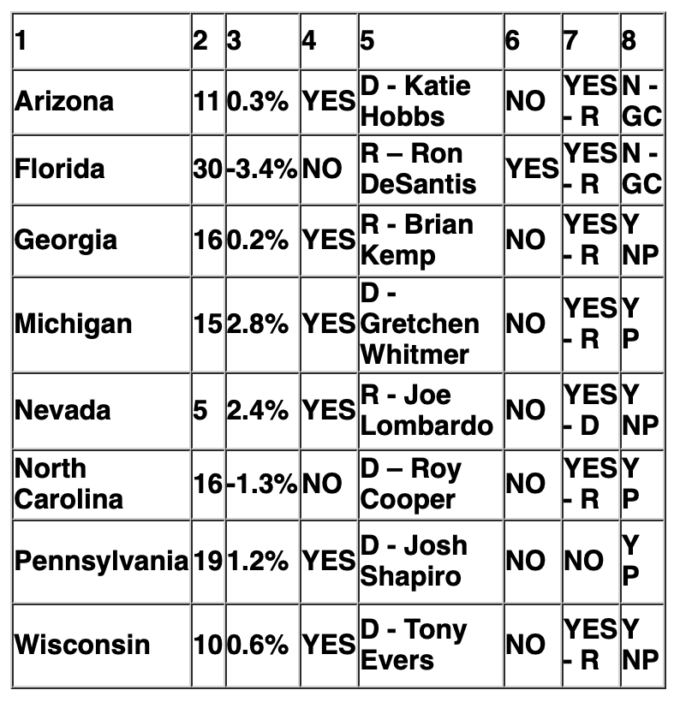

Moving from legal theory to practical politics, a comparative assessment of the eight swing states with the closest presidential races in 2020 shows what the impact of a SCOTUS decision would be if they eliminate either of the above conditions.

Table showing how ISLT could influence the presidential election results in the Swing States where Biden has less than a 3 percent margin.

1) State

2) Electoral Votes for 2024

3) The margin of Democratic Pres Vote in 2020

4) Trump’s legal team Challenged the Election Results

5) Governor – R or D

6) Does the legislature have the votes to override a Governor’s veto

7) Does one party have the majority in both state chambers

8) Are the Supreme Court Justices elected Y P -= Partisan; Y NP = Non-Partisan; N – GC – Not Elected but Governor Controlled

There are several takeaways from this table. What is initially apparent is that only in the six states where Biden won were the results considered invalid by former president Donald Trump who lost those states. These are the most likely states which will have close elections again in 2024.

In four of these six states, Arizona, Michigan, North Carolina, and Wisconsin, the Republicans control both state chambers, and the governor is a Democrat. Suppose SCOTUS decided that a Governor could not stop the legislature from determining who should receive the electoral votes. In that case, the ISLT could transfer the state’s electoral votes to the candidate who lost the popular vote.

It is most likely that SCOTUS’s main decision is whether state legislatures can ignore their supreme court’s ruling to stop any transfer of elector votes. It is possible that SCOTUS could decide in favor of a robust ISLT and deny a supreme court’s authority to intervene. In a close national presidential electoral vote count, having just one state switch its electoral votes could alter who becomes president when Congress confirms which candidate becomes president. It would be legal, and there would be no need to have a mob attack the Capital.

There is one last scenario that, at first glance, may appear to be a victory for the Democrats. However, it would leave the door open to the ISLT being used. The more “liberal” justices could succeed in preserving a state supreme court’s power to stop their state legislature from negating the results of a popular vote. Nevertheless, if the state supreme court concurs with the state legislature, the ISLT would be in effect.

Relying on a non-partisan state supreme court ruling is not a sure thing. In Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania, the justices are voted into office through partisan elections. Just as important, even in non-partisan elections, which Georgia and Wisconsin have, independent expenditure committees, from either the left or right, can greatly influence the vote.

The conservatives have significantly outspent and out-organized liberals in having their candidates win judicial seats at the state level. Consequently, judicial elections in these five states during the next two years will see immense outside-state contributions flowing into those states.

A system representing the people’s will within each state only occurs when an election is conducted fairly and certified as such, which is what happened in 2020. However, a very partisan legislature could reject a fair and certified election if SCOTUS approves the ILST.

The only way to prevent legislatures from using the ILST to overturn elections is for citizen activists to be involved in their state judicial races. They must question the candidates on where they stand on the ISLT. Any waffling from a candidate would be a sign that they could support transferring the results of a popular vote to the loser due to an unsubstantiated accusation that the vote count was corrupt.

Citizens must demand that any move to disqualify election results must be backed with verifiable data, not imaginable villains who are interfering. Unfortunately, that approach has been used in this past November’s election by a few Republican politicians who have borrowed a page from former president Donald Trump’s playbook.

The Supreme Court, in deciding the Moore v. Harper case, must not feed into a zeitgeist of conspiracy theories. If they embolden ISLT, they will perpetuate a theory that serves only to disrupt the institutional norms that sustain a democracy.