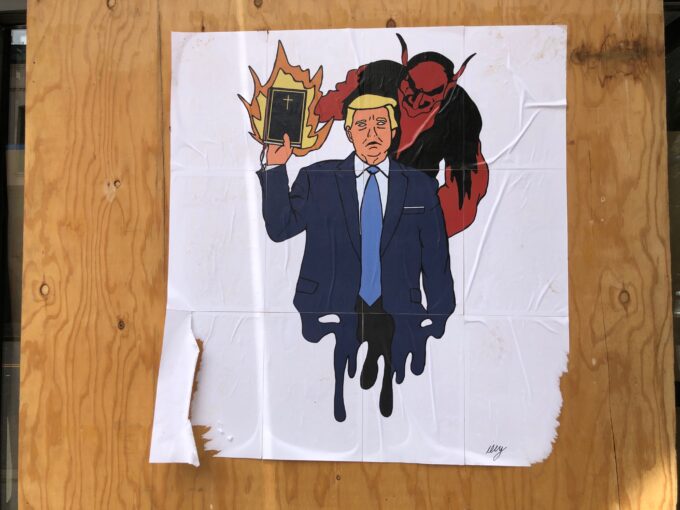

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

I was prepared to write an article condemning the mainstreaming of Trump’s populism. About 300 Republicans who deny President Joseph Biden’s victory in the 2020 election were GOP candidates on the national and state levels. But many of the candidates specifically backed by Donald Trump like Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania were not elected. In the end, however, about 80 election deniers were elected to the House of Representatives.

Is the craziness of the Trump era over? While the final results may not be known for a while, such as the Senate race in Georgia, the ballyhooed Red Wave has not taken place, contrary to many of the pre-election polls. Traditionally, in midterm elections, the party in power loses 28 seats in the House of Representatives and four in the Senate. President Barack Obama’s party lost 63 House seats in 2010. These midterms have not followed that tradition.

Trump announced that he would make a major announcement on November 15. His assumption was that he would triumphantly use the midterm Red Wave to position himself for the 2024 presidential race. Given the closeness of the House and Senate races and the obvious weakness of the Red Wave, the Trump wave could well be over too.

President Biden kept saying the election was about democracy vs. autocracy and now says that “the midterms were a good day for democracy.” In Obama’s terms, the Democrats were not “shellacked.” But instead of talking about winning or losing an election, we should be talking about the society’s mental health. Did the midterms put the craziness to rest?

The weakness of Trump and his supporters in the midterms could be the end of the Trump era. If so, how will history look back on Trump and his popularity? One way would be to examine America’s mental health. Was the Trump era a manifestation of a country gone off the rails?

Today we are attuned to individual mental health issues. When athletes like Naomi Osaka, Simone Biles or Michael Phelps go public about their depressions, we are aware that even stars, those who seem to have it all, can have psychological problems. Rather than a traditional taboo, mental health is emerging as a problem similar to physical injuries. “Osaka withdrew from the French Open because she wasn’t feeling up to playing,” could be similar to reporting that she had a sprained ankle. The mental and the physical, although not yet on a par, are not as separated as they once were.

What about societies? How to measure the mental health of a society? We measure how well a country is doing by all kinds of economic indicators such as Gross National Product, level of unemployment, value of currency, stock market prices, and so on. Except for tiny Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index (GNH), we are tied to economic indicators in evaluating societies. And even Bhutan’s GNH is tied to how individual people in Bhutan have achieved happiness, or, rather, how they feel they have achieved happiness. The GNH is individual and subjective, not an objective, societal measurement.

Can we measure the mental health of an entire society? When I asked a noted Swiss historian why he had spent his academic career studying Nazi Germany, he frankly responded: “I am fascinated by how societies go crazy.”

What does it mean for a society to go crazy?

The Washington Post reported the following: “Election deniers will be on the ballot in 48 of 50 states and make up more than half of all Republicans running for congressional and state offices in the midterm elections. Nearly 300 Republicans seeking those offices this November have denied or questioned the outcome of the last presidential election.”

When an individual denies an obvious reality we call it cognitive dissonance, defined as: “When two actions or ideas are not psychologically consistent with each other, people do all in their power to change them until they become consistent.”

Can a society have cognitive dissonance? Many Republicans tried to make acceptable that: the 2020 election was stolen; Joe Biden is not the legitimate president of the United States and Donald Trump, the billionaire, represents the average American. Nor do Trump’s numerous criminal indictments disqualify him from advocating his role as a great believer in law and order.

What opinion columnist of the New York Times Maureen Dowd calls The Marjorie Taylor Greene-ing of America is an apt description of a movement from the fringes to the mainstream and for societal cognitive dissonance. Greene, a member of Congress from Georgia, has gone from being a pariah for her extreme positions following QAnon and other conspiracy theories, and from being stripped of her two House committee positions to being someone who was in demand for her endorsement by Republican candidates in the current election. As the journalist Robert Draper describes her: “Over the past two years, Greene has gone from the far-right fringe of the G.O.P. ever closer to its establishment center without changing any of her own beliefs.” Greene was re-elected.

We should take a step back from the midterms and ask: Did an entire society correct its madness? If the level of cognitive dissonance goes beyond a limited number of individuals, when more and more fringe beliefs become more than marginal, it is no longer a question of political polarization. We are talking here about an entire society’s cognitive dissonance, about its mental health. Did the midterms put that moment to rest?

At a faculty meeting at Princeton University in 1968 in the midst of student uprisings, a distinguished professor asked: “Have the inmates taken over the asylum?” The fact that candidates like Marjorie Taylor Greene are taken seriously and even re-elected, raises the questions: Had American society gone mad? Is that period over?