The title of this piece may have been a bit misleading since I am not going to be providing an analysis of Ukrainian folk tales, though I’m sure there are Ukrainian scholars out there who could provide such an analysis; no doubt it would be extremely interesting. But I am not Ukrainian by birth, nor do I speak Ukrainian (my Russian is decent though). As such, I am neither qualified nor informed enough on the subject to even remotely do it justice.

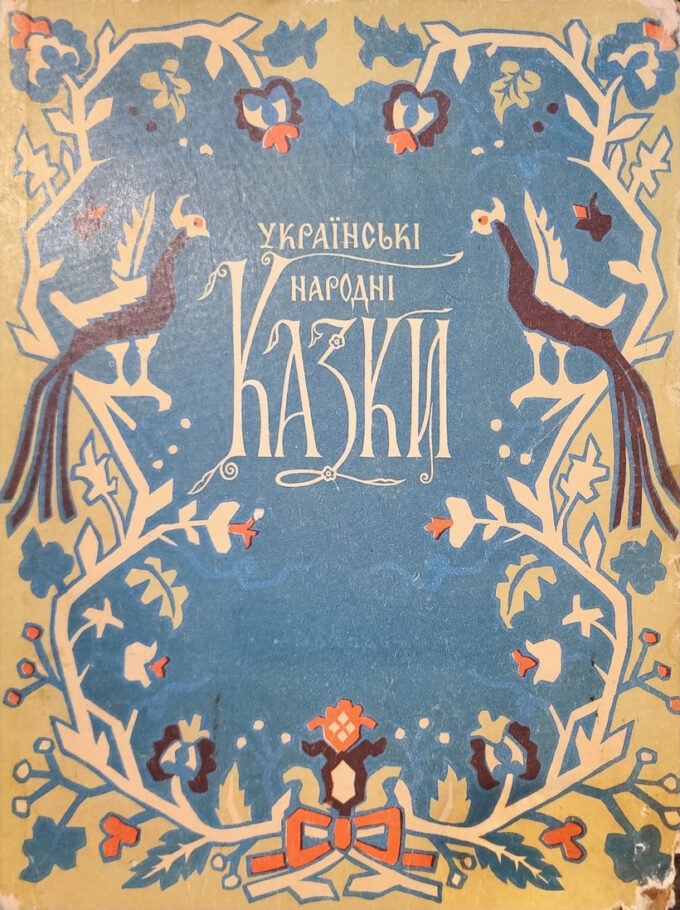

Instead, I would like to focus on the historical context of Ukrainian folk tales, language, and collective memory relative to life in the Soviet Union. Specifically, I’d like to tell you about the book pictured above and its publication, and what it tells us about life in the Soviet Union for Ukrainians.

***

My wife and I spent our Saturday at an antiquarian book and print shop here in the Hudson Valley of New York. The owner, a tall, funny, and supremely intelligent Aussie named David sat down with me for a chat. Together with his wife Cathy, David has been collecting and selling old books, maps, prints, photos, and other historical ephemera since the 1980s. Having just been in the shop the prior weekend by myself, David already knew my interest in all things Russian, historical, leftist, etc. Naturally, the conversation turned to Ukraine and the Russian war. After we each in our turn nodded in agreement at the other’s statements, David quite literally jumped from his seat and said, “I have something amazing to show you!” and quickly darted off behind a set of shelves in the other room. A few seconds later, he returns and places the book shown above in front of me.

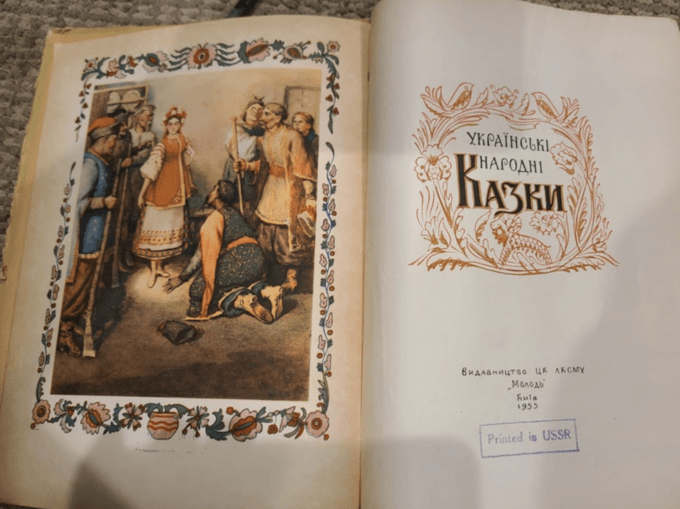

While, as previously mentioned, I don’t speak Ukrainian, the words on the cover were close enough to Russian to allow me to read the title: “Ukrainian Folk Tales.” I instantly knew that I had something very special in front of me, a relic of a very specific time in the Soviet Union. Let me explain.

As you already know, the tsar, and later Soviet leaders, suppressed most Ukrainian language and culture as part of the Russian chauvinist attitude toward the non-Russian peoples of the Russian (Soviet) Empire. Certainly, this was not unique to Ukraine as nearly every colonized people has had to endure varying degrees of oppression and cultural genocide irrespective of the imperialists in control (Russian, French, British, etc.)

But in Ukraine, this cultural erasure ran so deep that much of the population either didn’t speak their own native language or only whispered it among family and close friends. Ukrainian is dirty, embarrassing, a mongrel language compared to the great Russian mother tongue. Or so the internalized propaganda went.

And there was perhaps no Great-Russian chauvinist (to borrow Lenin’s term) keener on destroying Ukrainian nationhood, culture, and language than Stalin himself. Whether his forced deportation of Crimean Tatars or the famine often referred to as “Holodomor,” Stalin stands out as uniquely vicious and unrestrained in his hatred of Ukraine as separate and distinct from Russia. And so, throughout his time in power, Ukrainian language and culture was the subject of intense repression.

And so it was that only with Stalin’s death in 1953 did the Ukrainian language and culture again bubble to the surface. Despite the repression and countless dead or in a gulag, Ukrainian traditions survived. So, when Nikita Khruschev assumed power in the USSR and made his pronouncements denouncing Stalin and the excesses of his regime, the era that came to be known as “The Thaw” began as Soviet authorities relaxed many of the restrictions imposed by Stalin and returned to the idea promoted initially by Lenin of cultural expression for the peoples of the former Russian Empire.

1953 marks the beginning of this transformative period where finally Ukrainian language could once again be spoken openly, and even taught in schools as a “second” language. This was the period that my Uncle Emil studied Ukrainian language in middle school in Odesa, the time when the people of Ukraine began to rediscover that which had been taken from them.

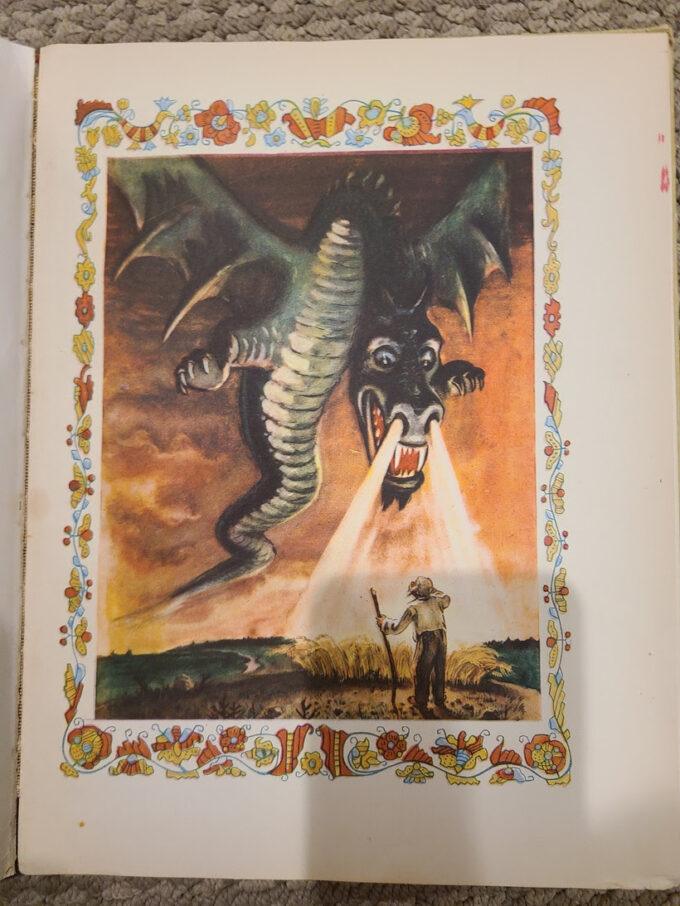

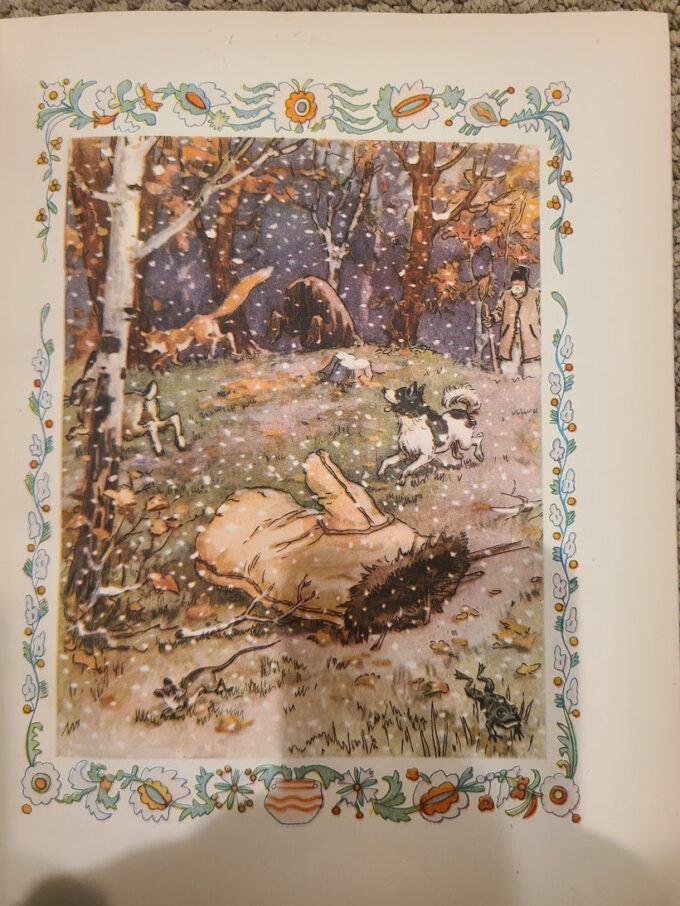

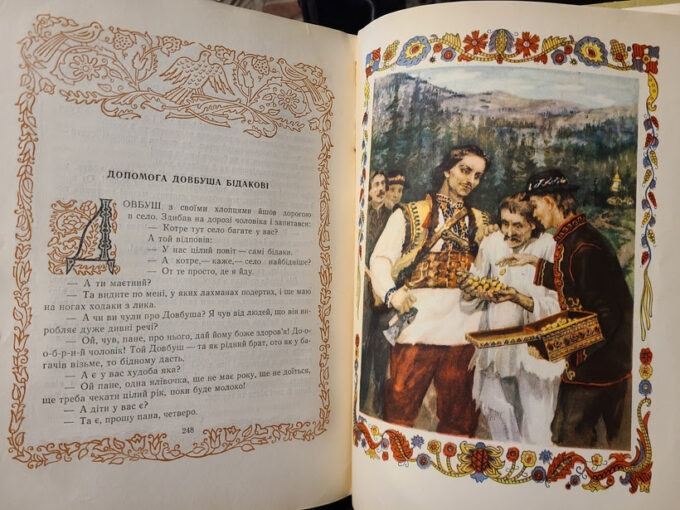

Which brings us to the book. In case it’s not entirely visible, the publication date on the book shows 1955, so just two years after Stalin’s death and the beginning of The Thaw. It is filled with the most breathtaking illustrations, each a work of art in its own right, depicting the various scenes of the folk tales contained within.

Now I want you to imagine for a moment that you’re my father’s age (born 1948) and you are shown this book as an 8 year old. It is the first time you’ve encountered anything like it: written in Ukrainian, filled with Ukrainian stories so different from the Russian ones you saw in your Kindergarten class. What would you think? How would you begin to understand the contradictions? Especially if, as in my father’s case, you’re a Jew and live your life within the Soviet Union as an ethnic other, a minority within a minority. The language of your school and business is Russian, the language at home is Russian and Yiddish, the cultural traditions ingrained in you since birth are Jewish and Russian ones.

The book is a revelation. A repository of stories, ideas, and expressions concealed from you since birth. How it must’ve seemed like something from another world finally seeing in visual form the stories you may have vaguely heard, if you were lucky, in passing mention. Imagine the joy of discovering a history and tradition you didn’t even know existed.

I wanted to share this incredible book find with you to illustrate the lasting impact of colonialism on oppressed and colonized peoples.

When Ukrainians fight today, they are not only fighting an invading army hellbent on destroying their country, their communities, and their lives; they are fighting for their history, their traditions, their ancestors. The young Ukrainian men and women understand, both explicitly and implicitly, that their fight is one for survival, not only for themselves and their families, but their history. They are saying to the invaders and to the world that they will not tolerate their land and their culture being stolen from them ever again.

And for those of us on the Left who continue to stand against this war of imperial revanchism and neocolonial subjugation, we must understand what exactly is at stake. Our solidarity is with all oppressed and colonized people. It is with those standing against imperialism in all its forms. It is even with those who don’t necessarily share our politics in all ways.

As Lenin famously wrote in “The Right of Nations to Self-Determination”:

“We firmly uphold something that is beyond doubt: the right of the Ukraine to form… a state. We respect this right; we do not uphold the privileges of the Great-Russians with regard to Ukrainians; we educate the masses in the spirit of recognition of that right, in the spirit of rejecting state privileges for any nation.”