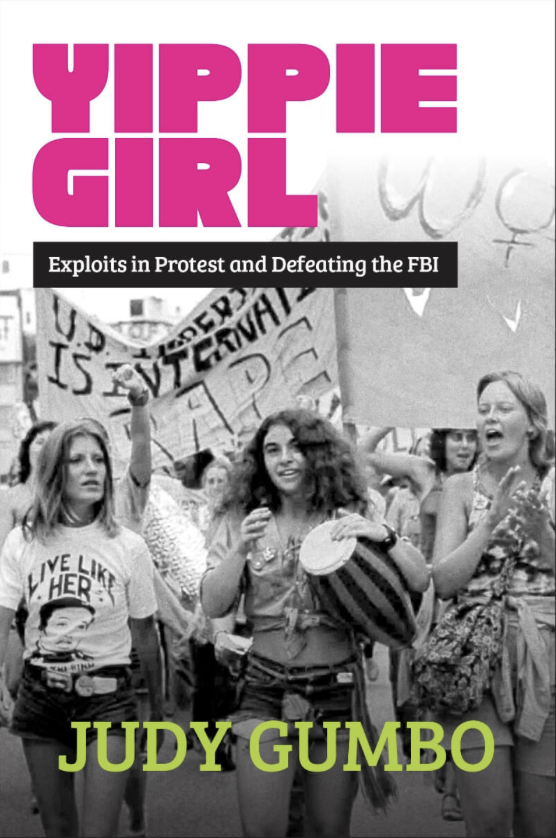

Photograph Source: udy Gumbo (center) at a 1972 anti-war protest in Miami. (Photo/Judy Gumbo Photo Archive)

My name is Judy Gumbo, I am an instigator and survivor of one of the most famous contested legacies of late 1960s counterculture – the gender conflict between women and men. I am also an original Yippie. Yippies used theatre of protest to satirize all we considered evil – especially racism and the war in Vietnam. You may recognize the names Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin. These male Yippie “leaders” were my friends. The women Yippie leaders Nancy Kurshan and Anita Hoffman were equally my friends. I put quotation marks around the word “leaders” to make clear that, as Abbie often said, “Yippies aren’t leaders, we’re cheerleaders.” And finally, my speaking and writing is also based in the 10 lbs. of unredacted FBI files about me that I possess.

My goal today is to give you a glimpse into what I and my compatriot women experienced more than 50 years ago as we worked at two famous alternative newspapers: the Berkeley Barb, and the Rat in New York City. Alternative papers like these were the primary vehicle we counterculturalists and progressives had in those pre-internet days to counter the biases we experienced in mainstream media. But at the Rat and the Barb our countercultural ideals of equality clashed with the shared misogyny women experienced — especially politically motivated radical women like me. The Barband the Rat represented two separate realities – The Barb is an example of what women had to fight against, The Rat provided us an inspiration of how to do it. Ultimately women took over the Rat and kicked men out, in Berkeley, Barb staff of every gender went out on strike and created a competing paper, the Berkeley Tribe.

The Berkeley Barb was an aggregator, a Huffington Post with sex ads. My job was to coordinate those sex ads. My ads upheld the lowest end of the Barb’s revenue stream; the paper’s economic engine was powered by full page display ads for records, concerts, and sex worker services: “BIG BUSTED BROADS OVER 21 looking for easy work with groovy hours & good pay. For Men Only.”

The FBI defined the Barb’s mission correctly:

“In addition to sexual matters, the Barb opposes present leadership and authority in virtually every area of American life including government, business, labor, education, and religion.”

Max Scherr, the Barb’s editor and publisher was a balding 40-something leftie male, often humorous but also autocratic. Office gossip had it the Barb generated a profit of $300,000 a year. This figure may have been accurate. Or pot inspired exaggeration. Or both. The FBI claimed that Moscow funded our political resistance, and that Max paid staff a magnificent rate of $1 per column inch. By saying this the FBI, as was often the case, was wrong. Max’s reporters earned a Dickensian 25 cents a column inch, so that articles in the Barb wandered down a path of dense verbal irrelevances so reporters could add inches to their columns and thus earn more money. Max paid me, the classified ad coordinator, $3 a week.

Most women who worked at alternative newspapers in the late 1960s held lowly jobs like mine – which clashed with our decade’s countercultural values of racial and gender equality. My boyfriend Stew Albert and other male reporters (on the left but also on the right) wrote diatribes in the Barb about anyone we considered oppressed or marginalized. We reported facts as we experienced them directly then agitated our readers to rebel.

Not so for women. Two times out of three a photo or a cartoon of a naked woman appeared on the Barb’s front cover.

“Tits above the fold. It’s how ya sell papers,” was Max’s mantra.

For Max, profit was in command.

Here’s the contradiction: By standards of modern feminism, I ought to have been shocked, horrified, appalled, and dismayed at this blatant exploitation of women’s bodies for profit, but when I first started working at the Barb I was not. I grew up in Toronto Canada – coordinating classified sex ads challenged my Canadian prudery. And made me a more tolerant person.

Max is long gone, but I remain close friends with what we called his “common-law” wife Jane Scherr. On Wednesday nights, after the Barb was put to bed, we Barb staff descended on Jane and Max’s Berkeley home for our weekly meal. I’d find Jane bent over an ancient kitchen stove; her brown hair stringy from steam that belched up from pots of boiling water.

One Wednesday I asked Jane,

“Don’t you mind? Doing all this cooking I mean?”

Jane spoke so softly I could barely hear her.

“No. Not really. It makes me feel useful.”

Jane had no income of her own. Max did not give Jane money to buy food for the meals he commanded her to cook. Decades later Jane revealed to me that, to comply with Max’s demand for staff meals, she’d skim nickels, dimes, and quarters from the cash receivables Max had her deposit into the Barb’s bank account.

“It was never a good idea to ask Max for money,” Jane told me, “Because he would say no. Then call me stupid. Or a cunt.”

To assert ourselves and establish our identity, my friend Anne Weills and I organized a women’s group composed of female Barb staff. I recall Anne remarking, her tone morphing in my mind into the harsh critique my mother often used:

“Judy, there’s something I need to say to you.”

I flinched. Anne continued.

“Judy, you’re a strong woman. And you’re intelligent. Please don’t be offended but every time I see you, it’s bring Stew this, bring Stew that. Drive him here. Drive him there. You act like you’re Stew’s servant.”

“You’re wrong,” I snapped, refusing to believe what Anne said. “I’m my own person. I do what Stew wants because I want to.” “I’m just wondering is all. I didn’t mean to hurt your feelings.” Anne replied.

Today I label I’d my response to Anne denial. Anne Weills was a radical feminist ahead of her time.

By way of preventive atonement, Stew published an apologia in the Barb. He denounced hippies who believed it was cosmic  karma for women to clean up. Stew wrote that if he could not cook, he was not entitled to eat. Barb readers saw Stew vow—in print—that he would learn to cook his favorite meat sauce – which he did, a mere 20 years after the fact.

karma for women to clean up. Stew wrote that if he could not cook, he was not entitled to eat. Barb readers saw Stew vow—in print—that he would learn to cook his favorite meat sauce – which he did, a mere 20 years after the fact.

Max printed Stew’s apology. As if to equate all men with racist Southerners, Max titled Stew’s apologia I Am a Male Cracker. My name appeared in smaller type as Stew’s technical consultant. I grudgingly took that as a signal I had won this battle, unaware that it would evolve, as gender conflicts often do, into perpetual war.

The San Francisco office of the FBI, an institution not known for sensitivity to gender issues, reported to Director Hoover that Stew had written an article about male chauvinism.

I came of age in what I call the macho, hetero-sexist end of late-1960s protest. Some feminists labeled women like me “male identified,” implying, unfairly I thought at the time, that I took my primary identity from observing male leaders. I once labelled this period one in which I “learned and grew”—a phrase Stew coined that is patronizing but accurate. Today I call it preparation for the flood.

In April, fifteen women trooped into my second floor living room. Many of us were Barb staff and/or in relationships with a male protest movement “heavy.” (today’s influencer) Our jeans, boots, and hair down to our shoulders made us look as if we came from a boarding school for hippies.

Jane Scherr sat next to me; I was relived she had shown up. My friend Anne started in, “Those images in the media that turn us into sex objects and infantilize us—I hate them. They’re degrading.”

I deflected Anne’s remark with what I thought of as a Yippie joke. Like every joke, mine contained a grain of truth. I said, “I wish I had big breasts like they do.”

No one laughed. Jane whispered to me, her voice so low I could barely hear her, “Oh Judy, how do you dare talk like that out loud?”

“I hate the word chick,” Alta, a poet who published under her own imprint, Shameless Hussy Press, interrupted, a quaver in her voice as if any word that denigrated women offended her poetic sensibilities. She went on:

“A chick is a baby chicken. And a bitch is just a dog. I won’t let Simon call me an old lady either.”

To my surprise, Jane picked up the narrative. She said, her voice still subdued, her eyes downcast, “It’s a revelation to me how everyone’s experience seems to replicate mine.”

I told myself that my relationship with Stew did not compare to what I’d seen of Jane’s to Max. Still, Anne’s “you act like you’re Stew’s servant” comment had burrowed into my subconscious. I also bought into Eldridge Cleaver’s binary division of the world—I was determined not to be part of the problem; I was part of the solution.

“Who is women’s enemy?” I recall enquiring, “The Panthers hate the pigs; the North Vietnamese hate U.S. imperialists—who are ours?”

“Society,” came a chorus. “Men,” said a lone voice I did not recognize.

Provoked, I shot back, “Stew’s NOT my enemy. Didn’t you read the SCUM Manifesto? By Valerie Solanas? She shot Andy Warhol! With a .32 Beretta pistol! Almost killed him. Is that what we want?”

I was by then swimming in a sea of liberation struggles—for peace in Vietnam, for the liberation of Black people and all people of color, for the Chicago Conspiracy 8 defendants, even for sexual freedom (led by the self- identified Jefferson “Fuck” Poland). As an occasional writer for the Barb, I could be as political as I chose.

On May 13, 1969, I handed Max a call to action. I wrote that every woman in our women’s group or any woman who worked at the Barb, or planted flowers in Berkeley’s People’s Park, or joined a women’s consciousness-raising group, or took part in anti-war protests, adopt this fundamental principle: we women deserve equality and liberation.

Max printed my piece under my “Gumbo” byline. He headlined it: “Why the Women Are Revolting.”

I was not amused. Berkeley Barb in hand, I stomped toward Max’s space at the rear of the Barb office. Then threw the most hostile words I could come up with: “Max Scherr” I yelled, loud enough for all to hear, “you are a two-faced sexist pig!”

“Too busy. Don’t bother me,” Max replied, his bald head bent over a sheet of layout paper. He dismissed me with a wave of his hand.

Even though my article reads to me today like a turducken of rhetoric stuffed with cliche and basted with expletives, I still stand by my message: If it takes a revolution for men to accept that women are as good—in fact better—than men are, so be it. We will have our freedom. We will be equal. We will not be ignored.

On Thursday, May 15, 1969, I awoke to discover People’s Park surrounded by a chain link fence. A three-inch tall headline PIGS SHOOT TO KILL— BYSTANDERS GUNNED DOWN in black capital letters dominated the front cover of the May 16–22 issue of the Barb.

“Why the Women Are Revolting” appeared front and center on page 5 of that same issue. Max had ignored me, but he could not ignore what I wrote. I was incensed. And conflicted. Max had insulted me with his demeaning double entendre but believed my message important enough to appear in print.

By doing so, Max spoke my truth to the Barb’s 85,000 to 300,000 readers (depends on who I asked.) To become a free human, you must put your metaphoric tits above the fold, face down those who oppress you and by so doing find the courage to be yourself. Over time, Jane and every member of our Barb women’s group found that courage. For me it took six more months.

Revolutions come in stages. By 1969 I had stopped wearing a bra but I and many of my west coast contemporaries had yet to internalize the rallying cry that “the personal is political,” with which Carol Hanisch had revolutionized the east coast women’s movement that same spring of 1969. Many of us were, by then, influenced by the Black anti-colonialist writer Frantz Fanon. Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth had made me realize that, as a woman, I was no different from any oppressed person unwilling to admit the fundamental truth of their oppression.

THE RAT – ANOTHER FAMOUS ALTERNATIVE NEWSPAPER

Women at the Rat took more decisively feminist action than women at the Barb. By 1970, I was back in Chicago with Stew for the conclusion of the Chicago 8 Conspiracy Trial. Stew stormed into our bedroom, his blue eyes emitting those Zeus-like bolts of anger only Stew could muster. He waved a crinkled copy of the latest issue of The Rat, a New York City underground newspaper edited by Stew’s and my friend Jeff Nightbyrd.

Stew yelled at me, “Look where your punk-ass women’s liberation shit has got us now!”

To find myself on the receiving end of such misogynist verbal abuse felt as if Stew had betrayed the ideal human being, I believed him to be. I grabbed the paper almost tearing it. Robin Morgan, an original Yippie who had quit the misogynist Yippies early on to organize a protest targeting the 1968 Miss America Pageant for its sexism, had published an article in the Rat.

Robin titled her piece Goodbye to All That. In it, she denounced the Conspiracy defendants, male counter-culturalists, environmentalists, and ultimately every man on the planet for their patriarchal domination of women. Robin blamed Abbie for ditching his first wife Shirley like any philandering movie star. She castigated Jerry for enjoying media celebrityhood while Nancy remained unknown. She condemned Paul Krassner for joking about an instant pussy aerosol can and reeled off names of Movement women Paul had slept with. Robin ended with a slogan she printed in capital letters: FREE OUR SISTERS! FREE OURSELVES!

Robin went on to name names of women she believed needed to say: “Goodbye to All That.” Her list included many of my friends: Kathleen Cleaver, Anita Hoffman, and Nancy Kurshan, among others. In addition, Robin called out Valerie Solanas who had shot the artist Andy Warhol for, or so a Daily News headline proclaimed, “being too controlling.“ My eyes scrolled down the Rat’s type-heavy page as if I was a search engine. Then I saw it: “Free Gumbo!” I confess—I felt relieved. For my own self-esteem, I needed to be named as part of Robin’s illustrious women’s group.

Shortly thereafter the Rat women ousted all male staffers. A front-page headline on the liberated Rat read: Women Seize Rat! Sabotage Tales! But by 1972, due to internal conflicts combined with lack of income, the all-women’s RAT ceased to publish.

To forestall problems such as those on the RAT, Max decided to sell the Barb. To LSD guru Timothy Leary. From my favorite seat in my living room, I watched negotiations with Leary collapse. Leary, the world’s most famous advocate of freeing your mind, was too controlling. The Barb staff, including Stew and I, went out on strike for higher wages. Max fired us. He published a four-page Barb stuffed with sex ads and what I knew to be a truthful headline, “MAX IS A PIG.” We, the now former Barb staff, put out a competing paper, the Berkeley Tribe–a socialist, communal, people’s paper. We quickly banished sex ads as oppressive to women and replaced them with ads for concerts and records. With such a loss of revenue, the Tribe survived four years, the Barb continued to publish for 8 more years thanks to, you guessed it, full page and classified sex ads.

Women’s history is often sidelined or forgotten. To repeat: it was that ideological contradiction between the egalitarian ideals’ of 1960s counterculture and women’s direct experience in it that challenged and changed us.

I was not alone in the counterculture to embrace self-determination. In 1971, our telephone kept ringing; I never knew for whose relationship it tolled. Jane left Max took the kids then sued Max in a landmark case for palimony – a case Jane lost. Nancy called it quits with Jerry. She could no longer stomach Jerry patronizing her. Anne Weills left Tom Hayden. Rosemary Leary left Tim. Black Panthers Artie and Bobby Seale separated. Kathleen Cleaver stuck it out with Eldridge until she could no longer take it. When Anita and Abbie’s son America was a toddler, Abbie was arrested charged with selling cocaine and went underground, leaving Anita a single mother on welfare who used her Yippie talents to organize other women on welfare.

By 1971 even Abbie and Jerry no longer spoke to each other. Director Hoover had instructed his New York office to “broaden the gap between Abbott Howard Hoffman and Jerry Clyde Rubin, hopefully to split this scurrilous and completely unprincipled organization.”

Yippies, scurrilous? Perhaps, but unprincipled, never! But by then it was too late. the two most famous Yippies also split up.

IN CONCLUSION

For me, and the majority of my female friends, women’s contested legacy at countercultural papers was a binary, a both/and. Sexism, misogyny and patriarchy prompted us to fight established power. And in so doing, we evolved as individuals and helped create a women’s movement for collective, radical change at underground papers and in our world.

Abbie and Jerry did teach me many things, including the art of shameless self-promotion. So, I ask: Read my 2022 book Yippie Girl: Exploits in Protest and Defeating the FBI. When you do, you’ll meet not just my generation’s famous men, but equally the wonderful women who filled our streets and homes with protest. And continue to do so today.

This is the text of a speech given at At Contested Legacies: The Counterculture After 50, Northwestern Medill School, San Francisco, Friday Sept 30, 2022.