Image provided by the British Library.

This story is an excerpt from Black Suffering: Silent Pain, Hidden Hope (2020) by James Henry Harris, a reverend and Distinguished Professor and Chair of Homiletics and Practical Theology at Virginia Union University. His latest book is N: My Encounter with Racism and the Forbidden Word in an American Classic (2021). The classic in question is The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Harris has a different take on Finn’s value as a classic and Twain’s academic exemption from charges of racism.

#####

No one can hope to capture fully the Black experience in the United States. It is too vast and multifaceted—and filled with pain. Suffering is the constant, touching the first feet of the Africans on American soil. And suffering is very much present in today’s America, where hard won gains seem threatened every day.

I have chosen to approach the African-American experience through vignettes of suffering. Some of the stories are my own, and based on personal experiences. Others were revealed to me. All are authentic, and sadly representative of Black life around us. It is my hope that these small examples and illustrations of loss and distress will enlighten, and thereby help to alleviate some of the pain of suffering, for suffering is the Black experience in this land.

Some days I can barely write about it, but I write because I think about it every day. It’s a constant obsession that never goes away—not even in my dreams.

#####

Talking, laughing, drinking, dancing, kissing, eating. People are friendly and happy in New Orleans. Anesthetized by joy.

There is a festive feeling in the air. It fills your nostrils with an intoxicating whiff of cognac and bourbon. All you have to do is breathe and open your eyes to the bright sunshine or the pelting rains blowing off the lake. It’s the spirit of life where all the senses are stimulated by the simple fact of walking outside and stepping to the street corner—any street in the French Quarter. I love something about New Orleans. It’s like a pleasant dream. A circus ride. It’s a bubble. A time capsule of past and future. And just like that, in a flash, in the twinkling of an eye, I had a brand new memory, and “I saw a great white throne and him that sat on it” was not even a resemblance of God or an angel. The future was also before me in New Orleans. And, I could not escape the past, a past that kept raising its ugly head.

I was a long way from the bustling sound of the French Quarter. The music playing and the folks from everywhere dancing in the streets. From Royal Street to Bourbon Street there is a panoply of places where music and musty smells dance the jib with each other and cause the spirit of carnival to pervade the air. It is a place described as one of three great American cities. New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans. But, like its comrades in greatness, it is not so great for the hundreds of Black and poor people I saw begging for food and money. One man I passed by on my way to the plush and posh Bourbon Orleans Hotel and just a few blocks from the famed Carousel Bar and Mr. B’s Bistro—this old black man had cut himself or somebody had stabbed him. I noticed the blood soaked sock on his right foot and what appeared like a gushing hole in his leg where his sciatic nerve ran from his butt down to his ankle. The pain was all over his face as he hunched over and moaned and groaned.

As I came near I asked, “Do you need a doctor?”

“I’ll be alright,” he said quickly.

I was a bit shaken and baffled by the happy and carefree scene in the middle of the day, and in the middle of the street with trumpets playing the sweet jazzy soulful, blues sounds of the not-so-happy south. The incident also reminded me of the sorrow I felt in my spirit. In my mind, I thought it was a small sample of suffering and pain of the place we were headed to, the infamous Whitney Plantation of Louisiana.

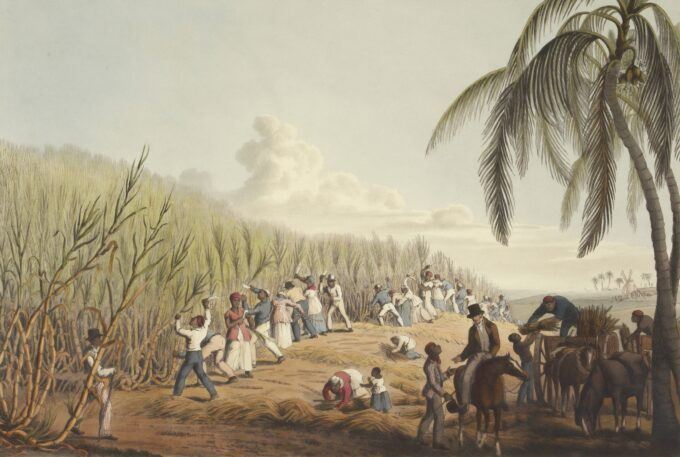

The journey was only a short bus ride away from the cityscapes. It took less than an hour to get there. The luscious foliage and the thick bushy trees along the highway quickly gave way to miles and miles of sugar cane fields and the big antebellum plantation houses that dotted the hillside along the banks of the Mississippi River. This is the same river that Mark Twain and Huck Finn talked about in their adventures, slavery, freedom and about nigger Jim.

The Whitney Plantation is a stone’s throw from the Mississippi River. You can see it in the distance as you stand in front of the slave Master’s house. It is a small house compared to Jefferson’s rambling Monticello estate or even his childhood home at Tuckahoe in Goochland County, Virginia. This Big House, the center of sovereignty, colonization, oppression, and greed, is modest in size and amenities. No fancy columns and ornate brick work like some of the more ostentatious mansions of Virginia and the Carolinas where tobacco was king and the flue cured golden leaf was the mark of the majestic cigars and cigarettes flavored by the sweet aroma of the sugar care imported from the plantations all along the banks of the Mississippi. The Mississippi River is America’s most notorious river where the bodies of thousands of Black women, men and children are interred from Northern Minnesota to the Gulf of Mexico. It is an American trope, a symbol of the slavocracy transporting slaves, cotton, cattle, tobacco and everything else from one plantation to another and to market all over the known world. Follow the Mississippi and you follow the tide of evil and hatred in America. I think of the Riverboat accident in Adventure of Huckleberry Finn when Miss Watson asked if anybody was hurt and the answer was “No. Nobody hurt. Just killed a nigger, That’s all.”

In many ways that type of thinking captures the spirit of white America not only in 1884 but even today nearly 200 years later where Black suffering continues to dominate Black life.

The Whitney Plantation is close to the main road. This surprised me because just a week earlier I had visited the Tuckahoe Plantation in Virginia and it is more than a mile off of River Road sitting on a bluff high above the James River which pales in comparison to rambling, curvaceous the mighty Mississippi. Both rivers have come to signify the means by which the commodification of the Black body was sustained over three hundred years of chattel slavery. When the Atlantic slave trade ended and the Middle Passage dried up, the James and Mississippi Rivers continued to propagate and facilitate the slave trade and the horrors and the torture of the slave auction block.

When I saw the small metal cage used to hold slaves for the auction on the Whitney Plantation, I felt the pain and fear of death. I felt sick to my stomach. I could see it. There was sorrow in my soul and my spirit grieved mightily. And yet, I decided to take a closer look, to step inside the torture chamber, the metal cage where ten bodies would be held in place by chains and shackles.

The day I stepped into the cage was the day I became a slave, transfixed back into 1732. The cage did it. It brought my memory back. It was hot that last day of March and suddenly I was being told what to do as a plantation hand. That was the day that I too had been sold down the river to the owner of a sprawling tobacco plantation. The rows were as long as the eye could see and the fields were thousands of acres large. My name back then was Robert Lee and the slaves all knew me. They were all calling me by name, but I was excited, telling them about my Ferguson, Missouri experience, and about Trayvon Martin and the big rally I had attended down in Sanford, Florida and they all looked as me as if I were crazy. And, I too understood their bewilderment because earlier that morning I had been in a breakfast meeting with a hundred Black professors and students from colleges all over the country. And now I was back on the plantation slopping hogs and working in the fields. My mama and brother were also there. My brother, Luther John, was seldom seen with the rest of us because he was very light skinned and special to Master Breckenridge, but my brother was despised by his wife. He had a real pair of cotton shoes and wore hand woven socks. None of the rest of us had socks and our shoes were made on the plantation by the blacksmith after he had fitted all the mules and horses. For the most part though, we were barefoot from about Easter to past Thanksgiving. We were always allowed to go to church on Sundays because the church was just a few steps from the Big House. We was real happy about that because Sunday was rest day. No picking cotton, no chopping grass, and no plowing the fields. On Sunday the food was also plentiful. It was the only day that we got our bellies full. I was always trying to get more to eat and sometimes we would steal a whole hog and cook it way back in the woods—about two miles from the Big House and then only when the winds was blowing south away from the house and across the river bank. We was not always good at this because the direction of the wind could be tricky (Dr. Harris, in this section you change voice again. If you are affecting dialect language, it is not consistent because one would not improperly use the verb “to be” as in “We was not always” in one space and “plentiful” in another place. Additionally, when the narrator was transported, in his narration, when did he assume a slave’s dialect? It’s subtle in transition, yet it does also seem unnatural.) One day, in late October, it was during the harvest, we had stole a hog and barbequed it and the smells of smoke and meat filled the air. And, for some reason the winds shifted direction without us knowing it. We was dancing and carrying on a plenty when somebody came busting through the trees on his horse. We knew immediately who it was. He always carried his six shot pistol and whip everywhere he went. When he saw us eating, dancing, drinking, and parading around the tree stomps we had made for tables, he began cussing and fuming like a wild beast. “You goddamn niggers are worthless dogs. The wrath of God is upon you this very day,” he said with red blood shot eyes and the fury of Leviathan. It was about twenty of us that day and the overseer Lee Winthrop was determined to find out who stole the hog from the master. It was a crime of high importance and could lead to death. He started with the old women trying to get them to snitch.

“Lucille, you tell me who did this? Who stole Master’s property?”

“Sir, Mr. Winthrop, I don’t know nothing about that. When I got here, we was already picking meat from the belly. The tenderloin, I reckon.”

He slapped her across the face and lashed her with the whip with a power as mighty as the East wind. She screamed so loud as blood splashed from her face and neck. As he flung his arm back to strike her again, her youngest boy, Moses yelled out to the top of his lungs.

“Stop! No. No. I did it. I stole the hog.”

“No you didn’t. Don’t do this son,” She cried and begged.

Overseer Winthrop, known as the evil executioner, hit the boy beside his head with his fist and then kicked him to the ground as everyone stood in fear rather than take the whip and gun from him and tie him to a tree and celebrate. It was enough of ‘em to do it and get away with it. He could have disappeared that day. But it never happened. He took Moses before Master Breckenridge who lectured him on the virtues of hard work, honesty, truth telling, and the love and wrath of God.

“Moses, boy, haven’t I been good and kind to you and the rest of my niggers?

“Yassar Master”

“Don’t I feed you good? You been getting your rations like the others.”

“Yessir, I been…”

“And you know God almighty don’t want you to steal or lie. Is that right, boy?”

“Yessir. The fear of God is the beginning of wisdom.” Moses could read the Bible.

“And, the Bible say thou shall not steal or lie. I teach all my niggers the Bible as God is my witness. You got something to say for yourself, boy?”

“No sir, but Jesus was crucified is all I can say. And sometimes I get real hungry and weak in my knees. We all do. Lord know we do.”

The master ordered all his slaves on the plantation to gather around the big oak tree on the coming Sunday after church and had Overseer Winthrop to lock Moses in the cage until then. On that Sunday, the preacher read from Paul’s letter to the Corinthians “slaves obey your masters. This is the word of God. This is the will of God.” After that, young Moses was stripped naked and tied to the big oak tree and whipped with thirty lashes until blood oozed from every crevice of his lanky, smooth black body. The men, women, and children were all made to watch as Moses’ mother sobbed and begged the Master to stop the beating before killing the boy. While she called on the name of God, Moses was left tied on the tree from high noon until sundown as the flies and ants tormented his bloodless body. He hung onto life until Monday at sunrise as his mother and other relatives prayed and called on God to help him. But, as the rooster crowed and the birds began to welcome the daylight, Moses gave up the ghost and died. He was only seventeen years old and had never left the confines of the plantation. There was little time to grieve as Master Breckenridge set the funeral for eleven o’clock the next day, a Tuesday morning.

The plantation church was full of slaves and the white families of both Master Breckenridge and Overseer Winthrop. The preacher, a short, white man in his fifties had done this ritual many times before because the Whitney Plantation was known to the slaves as the gates of hell, a death camp, a brutal and merciless place where evil was domiciled and the master was Satan, though he thought of himself as God.

I was there in the crowd that horrible day and I was an eye witness to the gruesome murder of my black brother. Moses was my friend and big brother. We was actually just two years apart. I was fifteen and he was seventeen. We would chase rabbits and run after birds and butterflies together and run around the yard near the Big House, but we could never go inside. It was forbidden by the slave laws and customs. Even if Master’s children invited us inside, we could not go in the Big House, that mistake would get you an awful and terrible beating because it was too much like acting like white folks.

One day Miss Salley, Miss Abbey, and Master Sam begged me to come in and play, but Miss Emma, the Big House cook, overheard them and screamed at me.

“Boy, you better stay out there, right there on the porch. Don’t cross into this door, you hear.”

“Yes, ma’am, Miss Emma,” I said.

“Boy, don’t you ever let Massar hear you say ‘yes, ma’am.’ You must always say ‘yessum,’ you hear me talking to you?’

Any child, man or woman slave would be lashed and punished for speaking too much like white folks. Sounding proper or learned was grounds for merciless punishment. Lynching. You had to always keep your learning a secret and never let any whites know that you could read or write. Like stealing food, reading was punishable by death on a cross. It was a high crime and an unforgivable sin.

I learned to read and write on my own. I remember one day when I was about seven or eight years old, I was helping the blacksmith unload some feed for the hogs and cattle and I noticed the letters on the bags. I looked at them and began to read. It said “The Louisiana Feed and Seed Company, Baton Rouge.” It just came to me and I blurted it out.

“Boy you can read? You can read?” said the blacksmith as he hugged me so tight I got scared. He was bubbling over with pride and fear too.

“I guess I can,” I said.

“Don’t you ever let Master know you got the gift of reading, you understand boy? Don’t let none of these white folks see or hear you reading.”

“Yes, sir. I’ll pretend to know nothing.”

“That’s good cause they’ll hurt you, I seen it happen here once,” he said trembling as tears rolled down his face.

“A boy your age, black as the night and more handsome than the gods of Africa slipped up and said ‘yes sir, my mother told me to feed the chickens.’ Do you know they castrated him and cut his tongue out? So that he would never speak again. I don’t want nothing to happen to you like that, you hear?”

“It was all because he sounded like white folk sound, saying, ‘yes sir and mother’ instead of yassa and mammy. Speaking too clearly was against the law and we could never look white folks in their faces. That too was considered acting too familiar for a slave.”

When I awoke from my dream the next morning, I was in a soul food restaurant in Charleston. I noticed that the Black lady’s hands were covered in flour and corn meal, a rich concoction of her special low country batter for anything fried. There were no baked foods on the menu. You could smell the bubbling grease in the parking lot before getting out the car. Martha Lou’s soul food restaurant in Charleston is a little cinder block hole in the wall. The small space is no more than a ten by fourteen foot square area where you can look directly into the kitchen and watch the shelling of peas and the stirring of boiling water saturated with sugar and butter as the rice is slowly dropped into the pot. The day I was there, I was the only black patron, and everybody else was white, garbling up the fried chicken, pork chops, fish, and green lima beans. One white lady who looked like a school superintendent was already over three hundred pounds as she shuffled to a table to place her order of fried chicken and fried okra and sweet tea. The cook was an old black lady with a readymade smile that I noticed as she waited on the young whites. I felt slighted because I was essentially ignored which is the typical way blacks treat other blacks. This is a holdover from slavery and colonialism in America. The white people were delightfully smacking their mouths. One guy said

“These were the best collard greens I ever had”

“Thank you so much”, the heavy black matronly lady replied.

The whole time I was completely ignored. I had to ask twice for a plastic cup to put my Diet Coke in. The can had been dropped on the small table as the waiter scurried to help another white person. The wall was filled with plaques and newspaper articles about the cuisine. A magazine, the Saveur proclaimed the cooks to be the best in the Carolinas. And the fried chicken to be the ultimate in delectability. Well, I was not impressed because the pork chop I had was a part of the leftovers from another day. It was tough and salty and the cornbread tasted like a cake with cups and cups of sugar added. It was sweeter than the iced tea. I didn’t learn that it was the fried chicken they were famous for until it was time to go. Even so, I felt like a stranger in the place. Even a slave maybe.

The next day I went to my undergraduate Alma Mater. It was on a Wednesday. I had to run all over the state to pick up my transcripts. I had no trouble until I got to my first school of higher education. You could smell the aroma of fried chicken. I was transported back in time because the process of getting a copy of the transcript is unreal. I had to fill out a request form in one building and then take that form across the campus to the cashier’s office and pay a five dollar fee and walk that receipt back over to the registrar’s office. They said, “Sir it takes 3 to 5 business days to get your transcripts.”

“Ma’am I’m sorry but I need my transcripts today. I don’t have that time to wait”, I said.

“Those are the rules”, she said.

“I’m sorry to ask you to do this, but it would help me if I could get them today”, I pleaded.

“Ah, ugh, ugh”, she sighed with disgust as I interrupted.

” I drove down here today from Maryland hoping to go back with my transcripts.”

“Have a seat back out there”, she said with alacrity and disdain.

“Thanks. I’ll wait”, I said without any hint of hubris.

Reprinted with permission from Black Suffering: Silent Pain, Hidden Hope by James Henry Harris copyright © 2020 Fortress Press.