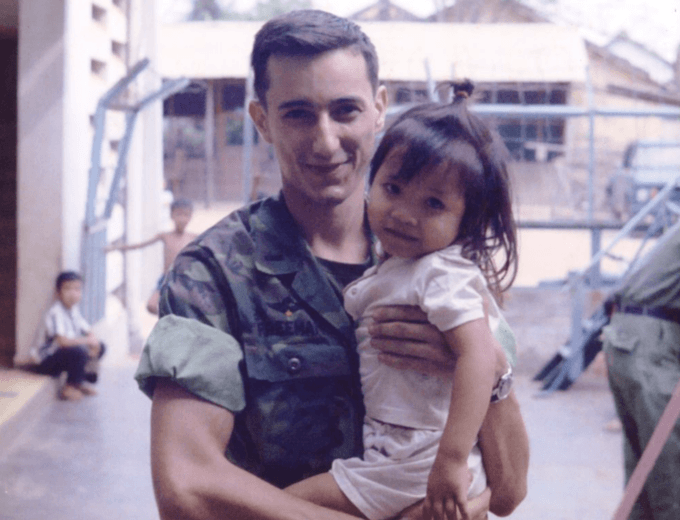

The author with the little girl who loved to have her picture taken. Sai Gon, 1970.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is horrendous. We have witnessed cities bombed into rubble. Children are grieving the loss of their parents; or have been maimed or killed themselves. The sight of these children has taken me back in time to an orphanage in Sai Gon.

Though opposed to the Viet Nam war, I went through ROTC in college. Between our junior and senior years, cadets filled out a “dream sheet” to request our branch of service, any special training we wanted, and where we would like to be assigned. Long tours were 2 or more years, and short tours were 12 months. At that time there were only 2 short tours—South Korea and Viet Nam. I requested Infantry, Airborne and Ranger training. For both my long and short tour, I listed Viet Nam. My reasoning, in part, was I owed a debt to my nation even if I didn’tbelieve in the war. Also, fighting in it was the best way to determine whether it was right or wrong. When I returned and spoke against the war, my time in combat gave me a certain moral authority the war mongers could not challenge by accusing me of cowardice.

Upon completion of my training, I was assigned for a few months to the 82nd Airborne at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, and then went to Viet Nam where I had the honor of serving as an advisor to an infantry company of the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Viet Nam) Airborne Division. At the time I was there (1969-1970), the ARVN Airborne Division was on a joint mission with the U.S. First Cavalry Division, one of the better U.S. divisions in the Nam. We operated northwest of Sai Gon near the Cambodian border, seeking out North Viet Namese units crossing into South Viet Nam through Cambodia.

The Viet Namese Airborne Division, along with the ARVN Marines and Rangers, were considered the three best units in the South Viet Namese army. I believe the ARVN Airborne was on par with any U.S. division in the Nam. In combat, the soldiers I advised were superb. In fire fights, “Charlie”, as we called the enemy, always paid a higher price than my men.

Aside from the pounding heat and constant thirst, most days our patrols in triple canopy jungle were uneventful. But when we found Charlie, or he found us, the firefights were furious, but generally ended relatively quickly. There were few pitched battles.

My job as advisor was to coordinate with First Cav choppers for combat assaults, medevacs, resupply, and extractions. During firefights, I directed Cobra gunships, and if needed, U.S. artillery. That was rare, as we had excellent ARVN Airborne artillery support.

Division headquarters (HQ) were at Ton Son Nhut Airbase in Sai Gon. Whenever companies came out of the field, that’s where we went. I wasn’t in Sai Gon much, but I did make a few HQ cade friends.

Every Sunday, members of the headquarters cadre, and some of the advisors in from the field, went to a nearby orphanage. We spent time with the children, and helped the orphanage staff with things they needed. We jokingly referred to these trips as military operations, first raiding mess halls for two or three pans of cake and at least one 5 gallon tub of ice cream. The mess sergeants were happy to help out.

On the preceding Friday or Saturday we would go to a PX for baby powder, baby oil, and anything else the children needed that we could buy. (I say “we”, though I was able to visit the orphanage only twice.) Occasionally, when the orphanage needed repairs we’d try to scrounge materials from construction sites at Ton Son Nhut, or buy them in Sai Gon.

Every Sunday the kids knew we were coming; and there they were, huddled close to the entrance, and gleeful when we arrived. Always, several children would rush toward us, and we knelt with open arms to hug two or three at a time. Our anticipation of seeing them, if only briefly, was as great as theirs. These were wonderful moments, and for my brother advisors who had kids back home, the visits were especially poignant. If they could not hug their own children, they at least could hold these kids, who we loved as much as they loved us.

But these children were casualties of war. They had lost their mothers and fathers, their homes, their family members. The infants could not comprehend what they had endured, but the older children knew, and a deep sorrow was etched on some of their faces.

We visited the orphanage for many reasons. Mostly it was the joy of improving lives rather than taking lives in combat. The irony of joyful afternoons, compared to jungle patrols and sudden death, was not lost on us. Most of the kids had been orphaned by U.S. air and artillery strikes on their villages—they were “collateral damage”, the Army’s polite term for innocent civilians caught up in the slaughter.

There were many sad stories about the orphanage children. Some were blinded, or had lost arms or legs. Or both. A few were scarred by napalm. I suspect and hope most of us have seen Nick Ut’s photo “The Terror of War,” and especially the video, of heroic 9 year old Kim Phúc, running down the road naked, her burning clothes ripped off, her left side covered in burns. If you have seen the film, you can see how truly heroic she was to stand there, stoically drinking water, as soldiers tried to treat her wounds.

Yes, our visits on those few Sundays were joyful, but seeing children scarred by American napalm ripped my heart out. I am not sure which was worse; the sight of child burn victims or youngsters who had lost limbs to U.S. artillery and aerial bombs.

Located in the orphanage was a long narrow space—“the limb room” we called it—about 35 x 12 feet, with windows looking into the orphanage along the front wall. To the left of the door, placed end to end, were two cafeteria tables. Down the center were two rows of three tables, with three tables along the back wall, and two tables at the far end. These thirteen tables were covered with artificial arms and legs for children. Peg boards were mounted across the wall opposite the windows, and also the wall at the far end. A vast array of artificial arms and legs, as if plucked from an army of life-like dolls, hung lifeless from those pegs. When a child outgrew an artificial limb a new prosthetic device would be taken and fitted to the amputated stump with the old limb stored in the limb room.

I have no idea how many child-sized body parts it held, but it was well over one hundred. From one orphanage, of the many throughout Viet Nam.

On the brighter side, after our joyous greetings, the children made a bee line to the cafeteria for their ice cream and cake. A beautiful little girl, about seven or eight years old—unfortunately, I do not have a picture of her—acted as the guardian of a small boy about five. He was legless and blind from a bombing attack that killed both his parents. The little girl would sit with this boy and help him eat. When he had finished his ice cream and cake, she would feed him hers. We knew she wanted it for herself, but always, she gave it to him. Her selflessness was astounding. Even now, thinking about her, this little angel, brings me to tears.

There was another little girl, four or five years old. Like most of the children orphaned by an American bombing run that destroyed her village. Miraculously, she had survived unscathed. She was very pretty, and very shy; but she loved to have her picture taken. The first time I went to the orphanage she hung back while the gleeful children rushed toward us. I tried to coax her to come near to me; but nothing doing, until the warrant officer who brought me took my camera and motioned to her to have her picture taken. Suddenly she smiled, ran to me, jumped into my arms, turned and posed for the camera. As soon as the photo was taken, she wanted to be let down. She had gotten what she wanted and kicked me to the curb. It was so funny, so sweet. I cannot express how badly I wanted to bring this child home with me. I sent the picture to my wife, who agreed, yes, if possible, we’ll be her new parents. But that was not to be. I have a mug, made by a friend, with the photo of the girl and I on it. I use it and think of her every day, and pray she has had a good life.

Yes, these children were “collateral damage”. What a cold and heartless term. Adult civilians caught in crossfires or murdered outright. Their children orphaned. Unless it is brought home to us, as the media finally did in Viet Nam, and as it is doing in Ukraine, we cannot realize the full cost of war, or its unspeakable losses. Bombed into ruins, cities can be rebuilt. But the dead are gone. And the wounded and orphaned are forever changed. Their scars, seen and unseen, will last their lifetimes.

Caught in the ravages of war, who suffers most? For me, it is the children. My heart cries for the orphans of Viet Nam. It cries too for the orphans in Ukraine. And for the children in Russia, who will never see their soldier fathers again.