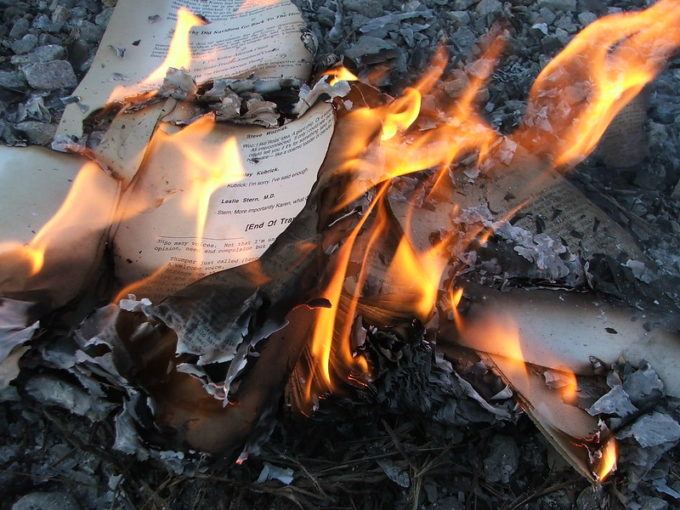

Photograph Source: LearningLark – CC BY 2.0

It was a pleasure to burn.

So begins Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, the story of a fireman named Guy Montag whose job is to burn books. “It’s fine work,” he says. “Monday burn Millay, Wednesday Whitman, Friday Faulkner, burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes. That’s our official slogan.”

Fahrenheit 451 is often found in the science fiction section of bookstores; yet again, its dystopian future is not too far off from America’s outlook. Just on February 2nd, a Tennessee pastor held a book burning, where copies of Harry Potter and Twilight were fed to the flames. Their fight against “demonic influences” was live streamed on Facebook, perfectly literalizing the subtitle of Chris Hedges’ 2009 book: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle.

This book burning, which followed in the footsteps of a Tennessee school board’s unanimous vote to ban the Holocaust graphic novel Maus from the school’s classrooms and library, clearly isn’t an isolated incident. In November 2021, during a school board meeting in Virginia, while discussing the removal of books from the curriculum and library shelves, board members expressed their preference to see the removed books burned. “I think we should throw those books in a fire,” one said. Another added that he wants to “see the books before we burn them so we can identify within our community that we are eradicating this bad stuff.”

Demonic influences. The bad stuff. Burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes.

Though not many school boards actually call for burning of the books, book bans in public schools are spreading like wildfire—Tennessee. Virginia. Missouri. Florida. Pennsylvania. Illinois. New Jersey. Utah. Kansas. Texas.

In the fall of 2021, Republican Texas State Rep. Matt Krause released a list of 850 books which primarily deal with race, gender, and sexuality. He advised school libraries in his state to report whether they had any of the titles compiled in his list of suspects. A school district in San Antonio removed more than 400 books.

Quick with the kerosene! Who’s got a match?

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom reports that in 2020, a total of 273 books were affected by challenges. In September 2021, the number of challenges were 67% higher than in September 2020. Since September, 2021, alone, the Office for Intellectual Freedom has tracked 330 unique censorship incidents.[i]

It only takes a match to start a fire. In an enclosed space at 30 seconds the fire grows rapidly. At one minute, flames intensify and spread, filling the space with smoke. At one and half minutes the fire devours everything in sight; the temperature reaches 190°F. At two and a half minutes, the temperature climbs above 400°F. At three and a half minutes, all that is in the room bursts into flames; the heat reaches 1100°F. At four and half minutes, flames engulf the whole house; rescue is no longer possible. From the initial flame to the smoke to the rapid temperature rise, the fire becomes life-threatening within minutes. Silent, almost undetectable, and yet deadly. The book bans that were kindled started out quietly but are spreading furiously now. The heat and smoke are insufferable; the damage is ever-growing by the second.

Commenting on the organized attempts to ban books in schools, Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the director of the Office for Intellectual Freedom says that during the 20 years she has been with the ALA, she has never seen a volume of challenges as high as it is now. The Office gets four or five reports a day for days on end, sometimes as many as eight. She testifies that many of these book challenges are instigated by social media and conservative organizations which mobilize local members to approach school boards and even show up in meetings to challenge books. “We’re seeing what appears to be a campaign to remove books,” she confirms, “particularly books dealing with LGBTQIA themes and books dealing with racism.”

Explicit. Divisive. Obscene. These are the charges against the books which amplify the voices of marginalized communities—authors, protagonists, readers—and the eclipsed corners of American history and society.

A book is a loaded gun in the house next door. Burn it. Take the shot from the weapon.

It certainly does not end with social media posts or school board discussions. Caldwell-Stone explains, “We’re particularly disheartened that elected officials who do have a duty to uphold the Constitution and the Bill of Rights are pressing forward with efforts to remove these books, as well.” “These challenges are also a violation of First Amendment rights,” she affirms.

PEN America’s extensive and in-depth report titled “Educational Gag Orders” discloses that between January and September 2021, 24 legislatures across the country introduced a total of 54 separate bills which are meant to restrict teaching and training in K-12 schools, public universities, as well as state agencies and institutions. The majority of these bills target discussions of race, racism, gender, and American history. “These bills appear designed to chill academic and educational discussions and impose government dictates on teaching and learning,” the report spells out, “In short: They are educational gag orders.”

The author of another challenged book that deals with race and gender, The 57 Bus, Dashka Slater comments[ii] that there is a double-prong attack here: One is through proposed laws and legislation. The second, covert and possibly more problematic one, is through creating an atmosphere of fear so that the teachers, librarians, school administrators who are caught in the middle of these culture wars, choose self-censorship.

If you don’t want a man unhappy politically, don’t give him two sides to a question to worry him; give him one. Better yet, give him none.

In October 2021, during the National Hispanic American Heritage Month, a parent at New Kent Middle School in Virginia complained that a book that was assigned in her kid’s class was inappropriate. She took to social media: “Our kids’ innocence is being taken away from them earlier and earlier.” The Superintendent immediately pulled the denounced book from the classroom, as well as the school library’s catalog. The book, which they refused to name “to ensure no other student could get to it,” apparently contained material that included abuse and child exploitation. Later the book was identified as the Winner of the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, the Michael L. Printz Award, and the Pura Belpré Award, and a New York Times bestseller The Poet X by Elizabeth Acevedo, a novel-in-verse about a 15-year-old Afro-Latina heroine who discovers slam poetry to express her frustrations, complex emotions, and questions about family, religion, sexuality, love, self-acceptance.

In Minnesota, parents pulled their students out of an English class because they were reading Dear Martin—a novel that takes place in Atlanta, where a black teenager attending a predominantly white preparatory high school on a scholarship gets thrown to the ground and handcuffed by a white police officer. The school did not take the book away but told the concerned parents that their students could read another title if they wish. The alternate title they offered? Fahrenheit 451. Since then, five parents completely pulled their kids from class.

Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, August Wilson’s Fences, Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Jerry Craft’s New Kid and Class Act, Mikki Kendall’s Hood Feminism, George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer, Jonathan Evison’s Lawn Boy, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Kalynn Bayron’s Cinderella Is Dead, Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely’s All American Boys… A list too long to recount. American classics, novels, plays, graphic novels, memoirs, young adult novels…

Texas State Representative Krause, with his 16 page list, justifies his cause by saying the books “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.” Yet is this really about the students’ discomfort, their guilt or anguish? Is it really the students’ innocence at stake here or is it American innocence?

“The innocence. Innocence. And we love it. We want to stay pristine, untouched, ever-new, forward-looking, bright, unwounded,” late psychologist James Hillman had lamented. “As the country crumbles, they say, ‘The best of America is in front of us.’ We want to stay innocent, because if we once woke up, we would see murdered bodies from here back to the first colonists. Buffalo, bison, forests, Indians, Negroes. Dead. So we stay innocent. Innocent is the American form of historical repression.”

For Hillman, an addiction to innocence, “to not knowing life’s darkness and not wanting to know, either” constituted America’s “endemic national disease.” The ongoing attempts to preserve the state of innocence at any cost lead to ignorance and, perhaps more dangerously, an arrogance regarding this adopted posture of ignorance.

In James Baldwin’s words, “It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.”

The innocence that would burn books rather than read them. Burn hundreds and hundreds of books, if necessary, rather than remember, recognize, and reckon. Burn ’em to ashes, then burn the ashes, rather than learn and grow up. So the innocence strikes the match in libraries, classrooms, district to district, state to state, generation to generation, and watches the flames engulf the complex, complicated, conflicted, dark, disturbing, violent truths of this country, past and present.

The smoke detectors have gone off. The temperature keeps rising and rising.

It was a pleasure to burn.