I don’t remember exactly how I came to be in possession of a couple of issues of Warren Hinckle’s Scanlan’s Monthly magazine in the summer of 1970. Maybe it was through a friend back from a visit to the States or maybe I actually bought it at one of the newsstands in downtown Frankfurt am Main that carried English language magazines and newspapers from the Herald Tribune to the Berkeley Barb. However,I do remember reading every word of both those issues. The information was right up the alley I was looking to find. Radical politics, mind-bending art, some drugs and fantastical writing. Perhaps the most fantastical article of all was one titled “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved.” Not only was the writing an amphetamine rush with lots of colors, but the accompanying artwork also served to intensify the words splashed wittily and lugubriously across the magazine’s pages. Like many other youthful readers of English, that was my introduction to Hunter S. Thompson and his artist sidekick Ralph Steadman. I was hooked.

The next time I ran into Mr. Thompson and his reporting was when Rolling Stone published Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. I don’t remember if it was every word of the piece that ended up in the book, but it was enough to ensure I did not miss a single episode of Thompson’s coverage of the 1972 US presidential campaign as he spilled it onto the pages of Jan Wenner’s counterculture/music weekly. It’s not that Thompson was as politically radical as the direction I was heading, but his writing was as intoxicating as a Dexedrine pill mixed with a bottle or two of good German beer. It even got psychedelic a fair amount of the time. The truth was that no writer had ever made political campaigning fun to read about while simultaneously exposing the vacuity and sheer piggishness of certain candidates and press people. Sure, there were some good examinations of the process—most recently Joe McGinniss’s The Selling of the President 1968—but nothing so raw and to the point written in real-time like Thompson’s coverage that year.

After the campaign ended with Richard Nixon back in the White House and ready to continue his race towards fascism, Thompson’s writing ended up being overtaken by the persona he had assumed. That persona, which involved exorbitant and often excessive drug taking and drinking plus a lot of hyperbolic posturing, not only defined him, it also limited his ability to change to something else. I am reminded of the Italian fiction collective which calls itself Wu Ming. This group of writers, who began writing under the name Luther Blissett, intentionally obscure their identities, insisting that it is the writing not the writer that matters. Of course, a personality-obsessed culture like that of the US depends on personalities to sell things. In Thompson’s case—given the time and the intended audience—the more outrageous the better.

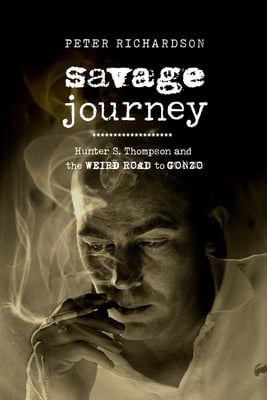

In his new book discussing Hunter S. Thompson and his work titled Savage Journey: The Weird Road to Gonzo, author Peter Richardson examines the interplay between the writer, his persona and his work. In doing so, he acknowledges Jack Kerouac and Tom Wolfe, both writers alive during parts of Thompson’s life. Richardson also places Thompson’s work in a lineage that includes Mark Twain and Ambrose Bierce. Both of these men also considered San Francisco their spiritual and emotional home—although neither they or Thompson would be considered spiritual by any conventional understanding of the term. Also like Thompson, they were quite popular for a time but had a few well-placed detractors. In other words, they ticked off the right people. In a chapter discussing Thompson’s legacy, Richardson quotes writer David Weir, who places Thompson’s work with the writing of many of America’s best-known muckrakers: “The kind of stories Thompson did were much like those of the early 20th-century writers Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Stevens or Ida Tarbell (or even further back, Mark Twain.” (211) The stories were about things the mainstream either avoided or judged negatively based on its prejudices. Furthermore, Thompson’s brash, occasionally abrasive and always-entertaining style was part of the message being transmitted. In its own way, his writing style and his persona gave a certain type of witness to the truth of Marshall McLuhan’s thesis that the media is part of the message, whether it wants to be or not. Richardson and other Thompson biographers make it clear that Hunter S. Thompson wanted to be; hence his hyper and hyperbolic public persona.

I’ve read every biography of Hunter S. Thompson published in English. I was slightly skeptical that Richardson, who is also the author of an excellent book about the liberal-Catholic-turned-radical-left magazine Ramparts and cultural history of the Grateful Dead, would be able to present Thompson and his work in a different light from the rest. Naturally, there are places where the story overlaps, but never is it stagnant or redundant. Richardson’s decision to look at Thompson through a literary lens not only works, it truly succeeds in adding a new level of comprehension and context to Thompson’s writing. A most deserving one, I might add.