The object of terrorism is terrorism. The object of oppression is oppression. The object of torture is torture. The object of murder is murder. The object of power is power. Now do you begin to understand me?

– George Orwell, 1984

They say that truth is stranger than fiction, but in these relativistic days of post-Truth reality (whatever that means), many of us have taken to writing in its shadow, or in the vacated location of its last known appearance. Creative Non-fiction is big now. It’s very big with the MSM, especially with its Tales of Yankee Power (as the Bard of Duluth would put it) coming from anonymous sources in unnamed highly placed positions, usually the Intelligence Community (IC). It’s John le Carré all the time now. Fiction and truth just aren’t that far apart any more in events that matter. If they ever were — that’s what postmodernism was all about after all: It depends on who controls the narrative.

The reader will probably remember Abbottabad 2011, the bin Laden raid, the showdown. Obama’s Counterterrorism chief, John Brennan, told the press Navy SEALs were in a firefight with UBL, and that “while bin Laden had vowed to go down fighting, in his last moments alive the master terrorist hid behind a woman.” As if anticipating criticism for killing the one guy who might have known about future 9/11s, Brennan added that UBL would have been taken had they been able to. He soon walked these details back. A video feed of the raid was said to have gone awry, leaving the narrative to hearsay accounts, and soon several different versions of what happened at the ‘showdown’ were reported. SEALs reached out to the public, 60 Minutes interviewed raiders, the “journalistic” Zero Dark Thirty was made, with the “cooperation” of the White House. There is even the local Pakistani media coverage that told a different tale. But it’s still uncertain what actually took place that early morning in Abbottabad.

But there’s another version of those events, KBL–Kill Bin Laden: A Novel Based on True Events by novelist JohnWeisman, which maintains close access to SEAL team members and Weisman, a writer praised by Seymour Hersh, has written about them before. Some facts can only be related as fiction rather than fact, and are truer as a result. In KBL, Weisman gives an account of ‘what actually happened’ at Abbottabad that is disturbing and riveting. SEALs coming up the staircase, facing UBL’s slightly ajar door, we get:

One round had hit just above the left eye. His head must have been turned toward the shooter because it exited out behind the right ear, taking a fair amount of skull and brain matter with it. Between the green light and the Ranger’s night-vision equipment, the blood and brain goo registered black. But that wasn’t all. The shock and kinetic energy had ballooned the head itself so it looked almost hydrocephalic…

Of course, the MSM is not likely, in their anal-licktickle kowtowance to report such glee. For all the horror of Wikileaks’s depiction of a war crime in “Collateral Murder,” little commentary has addressed the laughter of gunners on board the shooting choppers.

Weisman is even self-conscious, seemingly taking the mickey out of the Press for what it leaves out. Here, Weisman continues with the ‘showdown’ and comments, journalistically, on its eventual perception:

Whoa, Crankshaft’d [bin Laden had] taken a wholesome burst dead-center mass. Four, maybe five, maybe more rounds. Turned most of his chest cavity into squishy, bloody colored jelly. Faint fecal scent told the Ranger maybe they’d even nicked the colon. No way Washington was going to admit to any of that. The Ranger made himself a bet that the official report would read something to the effect of one round to the chest and one round to the head.

This is exactly how it was reported, early on, in the MSM. The same ABC report citing Brennan above added: “Bin Laden was shot twice, once in the head and once in the chest, a senior administration official told ABC News.” Oy.

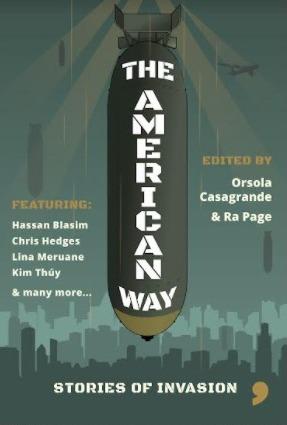

In The American Way: Stories of Invasion (Comma Press, 2021) edited by Ra Page and Orsola Casagrande, the narrative of ‘what really happened’ is explored by presenting 20 known US military incursions into the sovereignty of other nations — first, in the form of fictional stories, followed by an Afterword for each story that are more traditionally journalistic and politically analytical. The stories are conveniently presented in chronological order: Iran, 1953; Congo, 1961; Cuba, 1961; South Africa, 1962; Canada, 1963; Vietnam, 1967; Italy, 1969; Turkey, 1971; Chile, 1973; El Salvador, 1981; Guatemala, 1982; Grenada, 1983; Nicaragua, 1986; Kurdistan, 1999; Afghanistan, 2001-2021; Colombia, 2002; Iraq, 2004; Gaza, 2007; Libya, 2011; and, Pakistan, 2008-16. We’re reminded that this list is the tip of the iceberg, but, even so, demonstrates a level of bellicosity toward the world, a posture of conditioned and doctrinary privilege, that has taken up some 75 years of post-WW2 threat. What do “we” have to show for it?

In the introduction to The American Way, the editors seek to have the reader consider the tales to follow in the light of the shiftiness of language. This is a phenomenon that is both the proverbial curse and the blessing of meaning. I recall T.S. Eliot complaining (as if, right?) about its imprecision:

Words strain,

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,

Will not stay still.

The point here is that language, even for ourselves, when we can call ourselves masters of it, struggle to get it right. It’s a total mess when it comes to others (and their struggles), and the theatre of politics and of public discourse. This natural quandary built into consciousness also allows for flexibility. With it a lame excuse for war can become a Noble Cause. LBJ, on the other hand, simply pulled down his zipper, flashed his cyclops, and said, “That’s why we war.”

But the editors are over Eliot; he’s so tse-tse. They bring in Harold Pinter for the heavy lifting. And in an age when we must daily endure the dreadful bloviations of the MSM about conspiracy theories, while we watch as they hide from view ‘anonymous’ sources playing them with the politically motivated leaks designed to con us. Ra Page and Orsola Casagrande like what the Nobel Prize winner says:

Pinter seemed to place the blame for this distortion not on the parroting media, but on language itself. There is a ‘disease at the very centre of language,’ he wrote, ‘language becomes a permanent masquerade; a tapestry of lies.’

This sounds uncomfortably like Turd Blossom’s modus o as he attacks “reality-based thinking,” the major difference being that Karl Rove (i.e., TB) sees the ‘disease’ as an opportunity to manipulate and take control of a narrative and the reality it’s supposed to underpin. Some of us also remember the dressing down Pinter gave the Yanks with his 2005 Nobel Prize for Lit speech that attacked American foreign policy. Come to think of it, Pinter’s speech was like the opposite of Obama’s 2009 Peace Prize speech where he licked the war-flavored ice cream cone until only bone was left.

The editors remind the reader that the US sense of expansionary mission goes back to the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which proclaimed the right to intervene in Latin America. The presumptuous posture is carried on through so-called Manifest Destiny and the Pax Americana. But the editors see it all as neo-colonialism and the defilement of language. They posit, “Central to the US’s domestic PR strategy was the weaponization of ‘values’ in the

cause of empire – Pinter’s ‘disease of the language’ writ large.” How do they get away with it? Again, language. The editors suggest that the MIC control the narrative and feed ignorance:

But how is this domestic doublespeak, this mendacity back home allowed to take root? A primary vector for Pinter’s ‘disease of language’ must surely be simple ignorance. Many of the interventions featured in this book remain relatively unheard of, even in the countries where they took place, let alone back in the States.

(Liberal) Education is the key, Chomsky tells us, and we tell ourselves that it is the mission of the MSM to keep our democracy well-informed. A little Socrates or a lot of hemlock: You choose.

Ra Page and Orsola Casagrande are both former journalists. Page is the CEO and co-founder of Comma Press, a small press publisher specializing in human rights. He has edited over 20 anthologies, most recently Resist: Stories of Uprising (2019). Casagrande worked for 25 years for the Italian daily newspaper il manifesto, and is currently co-editor of the web magazine Global Rights. The two write of their motivation for putting together this collection:

By commissioning a series of short stories and essays on the history of US interventionism, this book hopes, in some small way, to redress this corruption of language. To begin with, it rejects the assumption that we live in a post-colonial age; the centres of empire have merely shifted, not gone away…[We need] to genuinely inoculate against the disease of language that infects those who benefit from empire, we have to turn our ears solely to those on the wrong end of it; the colonised. ‘

The stories are essentially works of creative nonfiction, as if, say, the pieces in many a Counterpunch issue had an accompanying fictional tale built around.

The book of stories and commentary features IPAF shortlisted Libyan author Najwa Bin Shatwan and Jhalak Prize winner Jacob Ross, and includes Payam Nasser, Fiston Mwanza Mujila, Ahmel Echevarría, Peré, Paige Cooper, Kim Thúy, Huseyin Karabey, Lina Meruane, Gianfranco Bettin, Carol Zardetto, Jacob Ross, Gioconda Belli, Wilfredo Mármol Amaya, Gabriel Angel, Hassan Blasim, Fariba Nawa, Talal Abu Shawish, Lidudumalingani Mqombothi, Bina Shah, A Halûk Ünal.

There are myriad approaches to sampling such a collection: You can  dive right in anywhere; go regional; select familiar authors, etc. I’ve decided to look at four stories and commentaries most Americans are familiar with through the accounts of the MSM — Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan — as well as a brief glimpse into lesser known “invasions” in Canada and Italy.

dive right in anywhere; go regional; select familiar authors, etc. I’ve decided to look at four stories and commentaries most Americans are familiar with through the accounts of the MSM — Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan — as well as a brief glimpse into lesser known “invasions” in Canada and Italy.

The first entry in the collection is Iran (1953) and begins with the short story “Runner in White” by Payam Nasser, followed by the Afterword, “Black Gold, Red Fear ” by Olmo Gölz. Nasser’s story tells of the rise of the populist Mohammad Mosaddeq and the Anglo-American conspiracy to topple his government and restore the Shah to power. That was the plan anyway. “Runner” is told through the eyes of Parsava Amini, a little girl raised among principals involved in the rise and fall of Mosaddeq. Rouzbeh and Mehrangiz, her father and mother, are separated at the time of her birth, as Rouzbeh, a military scribe, is exiled after blowing the whistle on corruption at the academy. Parsava’s mother dies after giving birth to her, closing her life out with the words, “It is white everywhere!” This takes on mystical qualities in the story, as Parsava, too, sees Sufi-like visions of white that dervish their way through the tale as a backdrop to the political intrigue afoot.

In exile, Rouzbeh, a lyrically literate man, establishes a correspondence with Mosaddeq, which leads to further troubles with the competing forces of power at the time. He tells seven year old Parsava talent is a way of flying, and that people need to put their “talents into use” or they lose them:

He said most people are never allowed to fly, are never allowed to show their abilities. Most people are like hens that only lay eggs for those who wield power, and if they refuse, they get their heads cut off.

Call it a parable. And remember what Dylan said about thought-dreams being seen, and duck.

One day, while she wanders off to find pieces to complete a snowman, she witnesses her Dad, a Tudeh Party (communist) member, being chased by two hostile political agents, and has a collapse:

Parsava fell face-up on the ground. Her eyes half open, she could see the sky and the large snowflakes settling on her face. Then everything went black, and then all white. But this white was not the whiteness of snow. She felt her body floating in the air like a dandelion in a breeze…What she was experiencing dated back to antiquity, an ancient, forgotten reverie. Parsava was drowned in wonder. She looked around. She saw nothing but white.

It’s as if she’s swooned into a dervish dream. But lest we get caught up in magical swoons, Nasser tells us, “Parsava had an atrial septal defect of the heart that affects the blood flow to the lungs.” She takes after her mother, we’re told.

After her father gets out of jail and returns home, maimed from interrogations, he continues to write inflammatory prose, including The Midas Syndrome, which Nasser describes as a reverse tale where “Everything he touches turns into faeces.” The Shah’s henchmen are defensively unamused and he’s taken again. In the meantime, “Mosaddeq was gaining

more power by the day and gathering his supporters around him from every corner of the country.” This spells trouble for the Shah, who is driven out, but then Mosaddeq gets himself in trouble with the Brits when they learn of the possibility that “in less than a year parliament would pass legislation to nationalise the country’s oil industry.” No way, Jose. And M’s goose is soon cooked. Parsava soon fades to white, like Mom.

In the Afterword, Olmo Gölz pretty much expresses it all with his title, “Black Gold, Red Fear” — oil and communism. Over my dead imperial body, say the Brits. And the CIA (Operation Ajax). Enter the dracon: the Islamic Revolution of 1979. This led to an underreported border incident that Daniel Ellsberg discovers was as consequential the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Carter White House feared that the Soviets might invade Iran. Ellsberg cites an NBC report, which states, in part,

‘…The case was then, as it is to a large extent now, that if the Soviets decided to move in a major offensive into that region [as the White House feared at that moment, eight months after the Carter doctrine had been announced] then you would probably have to consider the use of nuclear weapons to stop them, Jody Powell, Carter’s press secretary at the time, told NBC.’

As the editors of the volume suggest, just because the Afghan occupation is over doesn’t mean new Hells aren’t ahead — Syria? Iran? Russia? China? Venezuela?

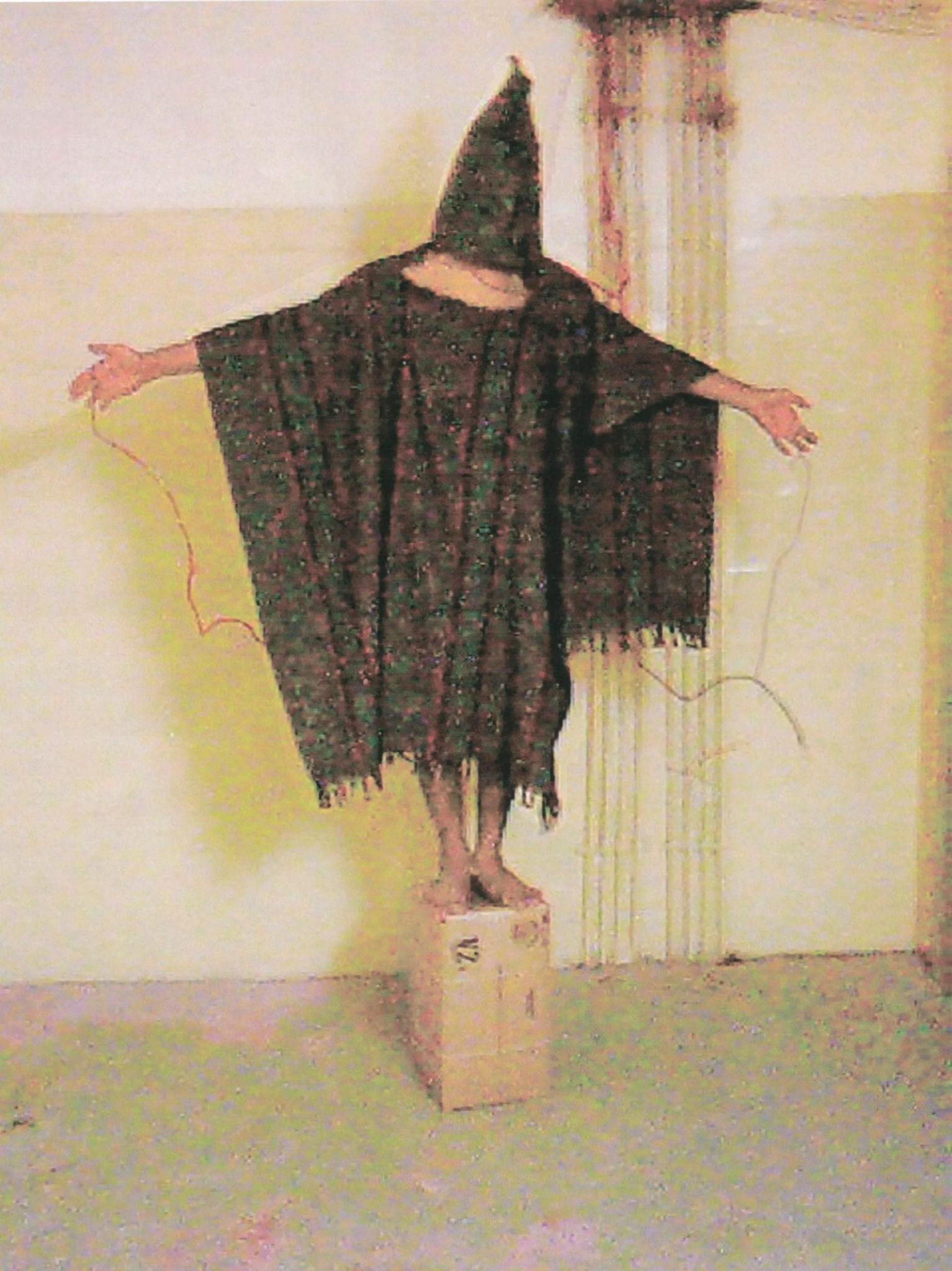

By now the story of how we invaded Iraq is widely disseminated, few seemingly disturbed, that the invasion was criminal in intention, and not at all about freedom fighting. “We” just rubbled Babylon, producing the film Three Kings to snarkily tell us what it was all about. In The American Way, the editors dish up the fictional story, “Babylon” by Hassan Blasim. It’s an almost-glib first person tale of two former prisoners of Abu Ghraib, under different regimes, to compare torture notes. We get a human portrait of the “torture celebrity” Khaled Ali — you know, the one on the chair with the black hood. Blasim’s first-person narrator, Adnan, further describes his poster boy status:

There was hardly a Western or Arab media organisation that hadn’t interviewed this ‘torture celebrity’ called Khaled Ali. I knew his story by heart. The Americans had chained him to the bars of his cell for days, beaten him, threatened him, humiliated him, stripped him naked, sexually abused him, taken pictures of him, tortured him with music and waterboarding, and terrorised him with dogs. He still had pains in one shoulder, his ribs and his left leg.

Otherwise, as our unnamed narrator tells us, Khaled’s a nice guy.

By chance, Adnan, a refugee living in swank and swinging Kreuzberg, Germany, looks up from his laptop in a cafe and sees his poster hero live and kicking. They hook up in conversation. Adnan introduces himself, Khaled carefully sizing up his merry interloper, and calls him a colleague. Their exchange goes,

‘How do you mean? Colleagues? I don’t understand,’ he said.

‘I was in Abu Ghraib prison too, but you’re a star and I’m a nobody, like an extra in a film.’

Adnan tells of his treatment at Abu Ghraib under Saddam Hussein’s Baath torturers, while Khaled walks him through the brutality he enjoyed at the hands of sadistic Yanks, as described above. (For a moment, I can relate to Adnan’s enthusiasm for hooking up with Khaled. I’d been a commando extra in Raid on Entebbe and got to meet Charles Bronson, star of The Mechanic, in a two-take scene where he explained the mission’s importance to Israel, and it was like meeting Moshe Dayan and the thrill of mowing lawns. Lots of golf courses in Palestine. Know what I mean?) End parenthesis.

Adnan and Khaled continue exchanging brutal remembrances of things past. Back in the day, Adnan tells Khaled:

The 49 days I spent in that cell awaiting execution was the harshest and most terrifying time in my life. The room was like a grave and we were crammed into it – communists, Islamists and Kurds. You can imagine what it’s like to be waiting for death in a miserable cell like that. We took turns to sleep, with some of us standing while the others lay on the ground because the room was so small. We shat in a bucket and the food was atrocious. Whenever someone was executed they would bring someone else to the cell.

Soon they blood buddy up and become larrikins addicted to cocaine and alcohol, talking of lighter topics — performing a skittish Hamlet while waiting for execution (Adnan was Ophelia); the book Papillon, the film with Dustin Hoffman and Steve McQueen; “I played some Nick Cave from my laptop, and he looked uncomfortable”; they “put his head between

loudspeakers and [would] play heavy metal” — and, afterward, a fit of laughter about their human-all-too-human condition.

Khaled recalls the song “Babylon” by Dave Gray, a nothing-special song that begins, “Friday night, I’m going nowhere /All the lights are changing green to red…” To Adnan’s confusion Khaled explains that the song was played one time between the heavy metal sonic bombardments and it changed him somehow. And since his release from Abu Ghraib he’s been on a mission to find Dave Gray, who he finally contacts — telling him he’s the guy at Abu Ghraib under a hood on a chair connected to electrodes.

Dave’s a bit taken back. Khaled goes,

‘I liked your song.’

‘Thanks, sorry, you know…’

‘No need to be sorry. I’ll never forget your song. I should be thanking you.’

‘Oh man, thanks, you know.’

Jeesh, Abu is probably rolling over in his shallow Ghraib at this conversation.

Blasim’s Adnan has a healthy handle on the absurdity of Empire involved, summing up it all up with, “The barbarity and hypocrisy of the world hasn’t changed since ancient times. It’s only the slogans and the justifications that have changed.” But for the intellectualized perpesctive, he brings in muscle man Chris Hedges for the Afterword, “The Invisible Government,” which is an overview of America’s Depp State and its history of torture and the subversion of governments that won’t kowtow to da bully. The CIA’s Sydney Gottlieb features in the dark programmatics of henched democracies. (See my review of Stephen Kinzer’s Poisoner in Chief: Sidney Gottlieb and the CIA Search for Mind Control.) The editors remind us that, though the book is called The American Way, the means, methods and modes presented in the book apply to any empire.

In Afghanistan (2001-21) the editors bring us into the new world of military reliance on contractors and prefabricated order to not only rebuild a nation “we’ve” attacked (Be the Chaos. Be the Solution.™), but to keep it stable with the introduction of contract killers to keep the piece — an old American Clintwood West fave, with tiny men and lots of no-accountability. “Surkhi” by Fariba Nawa presents the reader with an Afghanistan over-run with Afghan-Americans from Queens (refugees from the Taliban takeover) who’ve come back Home to save her by flaunting their Western corruption (material, emotional) and to fall in love with other like-cultured paramours. Raha and Sekander, American “feminist” and old world conservative male, having had a look-see of each other back “home,” have returned as contractors to help fix a broken Afghanistan.

Roha tells the reader: “I’m still a consultant. I was a lecturer in New York and came here to teach teachers about creative learning. The Americans still pay my salary.” Sekander works for a nebulous consulting company. But the locals have them both pegged and tell them so:

‘O sag shoi, is that what you were doing before America came to Afghanistan? You think you’re better than us, but you were just a dog washer in America and you get to be queen here. Take off those glasses so I can look at you,’ he sneered and spat on the ground, then rode away.

Roha and Sekander are seemingly semi-engaged, but, like men everywhere (remember that exchange between Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan in When Harry Met Sally ?), Sekander’s just “using” her as whored oeuvres before marrying the Pakistani woman his parents, back in America, have assigned him. Meantime, while Roha teaches creative learning, perhaps a euphemism for poor man’s Democracy with benefits, she not only risks being spat at as a “dog washer” but murdered by a primitive-thinking local with a Taliban-reinforced ethos about the place of women in society (even Afghan refugees in America, we’re told, expect old world values to be upheld). The Green Zone can be seen as a kind of USO development, an oasis in the midst of the horror, the horror, but still only temporary. Once the ‘titty girls’ are gone it’s back to greasing on the slippery slopes of war without any apparent reason.

In the Afterword, “Empire Privatised,” Dr. Neil Faulkner eschews the comedy-absurdity delivered by the fiction to provide a sober, though trenchant report on the privatisation of war that the Afghan theatre actually presents. All that deep dark chocolate money the US Gov doesn’t want to account for goes to contractors whose bodies go uncounted by the Press and whose unknown deeds are invisible. Lest we think that there is no point in Western troops being there in Central Asia except for the plunder of oil and rare minerals, Faulkner gives us the clarion call of Noble Cause rhetoric. We ask our exceptional selves:

What forces have conjured a world in which men believe they do God’s work in blowing up schoolchildren?

Where’s my Johnny 7? Sign me up! Forget about Sandy Hook. Waco. Oklahoma City. Value meals? But that’s exactly the shituation we left behind in our haste to get traditional troops out of Afghanistan and leave the T-bone steak for career contractors, lifelong subscribers to Hustler and Soldier of Fortune. Ten-hut! Pull my trigger.

But, Faulkner reminds, “our” rhetoric was never more than the bluffernutter sandwiches served up to an enabling MSM. In the late 70s, as far back as the Carter administration, when rural elders nixed much-needed reforms to inch their society toward, er, modernity, Afghanistan was doomed to endure first the hegemony of the Evil Empire, then the lesser of two evil empires, America:

And it was this, the reactionary resistance of the old rural Afghanistan, that triggered the Soviet invasion in December 1979. Then it was hopeless. The resistance turned into a conflagration – a guerrilla insurgency of Islamic mujahideen that transformed Afghanistan into Russia’s Vietnam.

To get the Russians out, with their tails between their dogma legs, the CIA worked with Pakistani provocateurs and set up the eventual al Qaeda, according to Richard Clarke, consigliore of multiple administrations. And then when the Soviet Empire collapsed, their dumpling done, they gave us back our Vietnam. Doh. Faulkner, all sound and fury, damn.

As we watch the friction heat up between China and America over the new “aggression that will not stand” (that’s why they make chaise lounges) at the hotpoint Taiwan that the Chinese see as a more offshore Hong Kong artificially protected by Yankee Doodle Dandy, Faulkner sums up all our fears:

The US is the single greatest threat to peace in the world today. This is because the US is in decline economically, yet remains dominant militarily.

It has a Crips and Bloods feel to it. Expect lots of drive-bys (maybe even through drive-ins)in the years ahead. Or the Big One. Ex-Nato Commander Admiral James Stavridis has written a trilogy of novels that moves us toward welcome wars with Russia (in the Arctic, oil) and, to start End Times off with a bang, a nuclear conflict with China during a sword-rattling exercise in the Taiwan Straits. So, no need to cut the military budget much before 2074, when, says the admirable Stavridis, “climate change comes home to roost.” (See my review of his recently released loony novel, 2034.) Until then, we LBJ the opposition. It’s depressing after a while, the history of hegemonic one upmanship.

This piece opened with a reference to the events of May Day 2011 and the raid in Abbottabad, Pakistan, to take out bin Laden (no forensics of his demise have been released, nor promised photos of his burial at sea, but “his” porn stash made the rounds and, apparently, UBL was not a MILF man). And Pakistan (2008-16) is as good a place as any for the editors to end the volume. In that time period, America has stepped up its drone strikes in North Waziristan, no longer worried about IDing specific “unlawful enemy combatants” but firing missiles at algorithmically determined suspects compiled in a disposition matrix — a kind of Minority Report fixation. Pre-cogs.

In “A Bird with one Wing” by Bina Shah, a family of 40 are on a bus on their way to a wedding in a village in Waziristan, a tribal nomansland and suspected refuge for “unlawful enemy combatants.” Zarghuna is relieved when the bus driver successfully maneuvers a notorious hairpin turn on a pass, when — “dum dum”– a drone wipes out part of the village below and hits the bus. Shah relates,

Broken glass crunched under her feet as she walked by the remains of her husband, her brother-in-law, her cousins. Some were intact, lolling backwards, others were taken apart, like butchered goats.

Zarghuna and her family were unlucky victims of disposition matrix:

Her family had thought it safe to go to the wedding, since it had been a long while since the last drone strike. That calculation had been their last mistake. And now forty of them had met God, but not her. And not her son, her bird with one wing.

Luckily, there is no report here of a ‘double-tap’ — taking out Zarghuna, when she attends the funeral of those killed on the bus, the logic being “we’ve” made an enemy of her with the first droning.

Zarghuna, crawling through the wreckage and carnage, man and machine mangled together, loved ones maimed and butchered by a robot overhead, vows: “Tomorrow the mourning would start, and perhaps in a hundred years there would be revenge.” This gets to the heart of Ian Shaw’s Afterword, “The Forever War.” A ‘cynic’ could argue that knowingly creating enemies this way guarantees a need to keep the US military ‘strong and vigilant’. Strange logic, indeed. As if Colonel Jessup from A Few Good Men code-redded a soldier and used the revenge-seeking actions of the victim’s survivors to justify more code reds. Can you handle that truth as a ‘national security’ foreign policy? It’s a bit psycho, like the time the CIA’s Duane Clarridge, former head of the Counterrorism Center under Reagan, after telling investigative John Pilger that he was happy to have participated in the overthrow of “What His Name” (Allende) in Chile, added that America would intervene “whenever it was in their national security interest to do so” and if the world didn’t like, it could “lump it.” US foreign policy in a nutshell.

The American Way: Stories of Invasion is chock full of lump-it stories. Not only the well-known atrocities Americans have had so little say over for decades, but even in surprising places like Canada (1963) and Italy (1969). You go, huh? Gianfranco Bettin’s “An American Hero” combined with Maurizio Dianese’s Afterword, “Scars and Stripes,” which work together to tell the story of the CIA’s intervention to suppress the commies:

Like Frankenstein’s monster, the project set up by the Americans to prevent Italy from ‘shifting’ leftwards and getting closer to the Soviet Union, got out of hand, even though they had complete control over key men of the project….

And, similarly, in Canada in 1963. more intrigue raises its ugly foot. Paige Cooper with “Condition,” and David Harper in his Afterword, “Dr. Ewen Cameron, De-Patterning and MKUltra,” re-tells the now oft-told beginnings of the CIA’s mind control experiments that began at a McGill University that included drug-induced comas, depatterning, and psychic-driving. The brainwashing technique is cinematically summed up in the montage scene from the film The Parallax View:

After viewing the excerpt, wait by the phone for further instructions.

The American Way is a depressing but necessary read. It’s educational in the Chomskian sense of reversing the effects of our generations long consent to murderous world hegemony manufactured by one Lesser-of-Two-Evil administration after another, in collusion with the mainstream media (MSM). The book represents an opportunity to quickly catch up on the nightmare doings resulting from “our” foreign policy decisions. I strongly recommend this book.

The American Way is available from Comma Press.