Dream factory. Notes from shop floor.

Is Thomas Jeffrey Hanks a Steely Mogul-Bossman or a Union Loyalist?

Can the Beloved Icon be Both?

Episode 1

Page from the website of one performers’ union political faction, “Unite for Strength.” Screenshot Dave Clennon.

HISTORY AND LEGEND

Once upon a time . . . in Hollywood, of all places … there was a feisty, robust labor union. It had a fighting spirit and it took pride in its achievements. It was made up of an unlikely crew of eccentric drifters and dreamers and passionate idealists from all over America — from the comfortable center of American society, and from its very fringes. This labor union was called the Screen Actors Guild. It could have been called the “Screen Actors Union,” but some of the founders believed “Guild” had a classier ring.

Nevertheless, many members of this union had no illusions about class. They knew quite well they weren’t “artists.” They weren’t “artisans” or even “craftsmen.” They were semi-skilled industrial workers. They were day-laborers, most of them, doing mental and physical work in a manufacturing process mostly less dirty and dangerous, but no more glamorous, than an automobile assembly line or a steel mill, or the orange groves of the San Fernando Valley or the docks of nearby San Pedro harbor.

Because they knew what unions are for, and because they had no illusions about “artistry” or middle-class respectability, these screen-entertainment workers succeeded in changing the Screen Actors Guild into a fighting labor organization, much to the displeasure of their powerful mogul-bosses (as well as some of the more financially successful members of “The Guild” itself). And these militant worker-unionists began to win real labor-struggle victories that improved their lives and the lives of the worker-performers who came after them.

It sounds fanciful, but I believe there have been moments when the Screen Actors Guild was a shining “citadel of labor.”

(For the record, the Screen Actors Guild — S.A.G. — no longer exists. In 2012, a confused and demoralized membership voted overwhelmingly to be absorbed into a larger, alien body, along with another, somewhat less admirable, and markedly less robust, performers’ union, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists — AFTRA. The larger, alien entity was named “SAG-AFTRA.”)

HOW TO BREACH A CITADEL OF LABOR

The Screen Actors Guild was flexing its muscle in a period of militancy. In 1980, the post-War generation of actors had ascended to authority and they were imbued with the spirit of the labor struggles of the 1930s and ’40s. They had already won landmark victories: they had established health and pension funds; employers were compelled to make contributions to those funds; the leadership and and the motivated membership had sacrificed greatly to achieve a huge milestone — royalties, or “residuals,” for previous work whenever television stations broadcast feature films or repeats (“re-runs”) of television programs.

This citadel of labor was strong, maybe impregnable, at least from the outside.

Thomas J. Hanks was an ambitious entrepreneur. He emigrated to Hollywood from Cleveland and tried his luck at the acting game, under the name “Tom Hanks.” His luck was very, very good. And the entrepreneur’s sights were set far above acting stardom.

But just before that incredible run of luck, just as his career was about to take off, he suffered a setback. More about that dark period after we flash-forward to 2021.

THE ELECTION

On September 2, 2021, SAG-AFTRA concluded its biennial election of officers and board members. These elections have serious consequences and some members, including me, felt that this election was tainted, due to violations of election rules and guidelines, as well as federal regulations. We filed protests with our National Election Committee and with our respective Local Election Committees. The National Election Committee, without explanation, claimed jurisdiction over all the complaints, effectively shutting out the relevant Local Election Committees.

We protesters alleged misconduct by a political faction in the union, known as Unite for Strength, and by that faction’s staunchest and most consistent backer, Thomas Jeffrey Hanks, listed in California Department of State corporate filings as Thomas J. Hanks, also known as Tom Hanks.

On October 7, the National Election Committee rendered its decision. They declared there was no wrongdoing by Unite for Strength or Thomas J. Hanks.

To understand the ethical dimension of the alleged wrongdoing by the political faction and its benefactor, it will be helpful to understand the political dynamics inside the citadel.

“WHICH SIDE ARE YOU ON, BOYS?”

There are two factional tendencies within SAG-AFTRA — as there were within both unions before they merged. At present, those factional tendencies, or parties, go by the following names:

(1) Membership First (M1st). The name was chosen, in part, because the partisans in this faction believed that the paid staff of the union had accrued more power, and better compensation, than the members, whose dues financed the staff’s work on the membership’s behalf, as well as paying staff salaries and benefits. The reality, these partisans alleged, was that staff was coming “first,” not the actor-membership. They asserted that they would change that relationship. Membership First was also animated by the combative spirit which had guided the Screen Actors Guild to victory in the past.

(2) Unite for Strength (UFS). This faction chose its title because their original driving issue was to merge (“unite”) SAG with the other screen performers’ union, the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, AFTRA. It was never clear what the “strength” in the party name was to be used for.

The entertainment press have not employed helpful descriptive terms when writing about Membership First and Unite for Strength. The trade papers and the Business and Calendar sections of the LA Times have generally described Membership First (M1) as “militant.” In periods of labor-management tension, the Hollywood media resort to stronger terms — M1st, or its leaders, are “hard line” and, occasionally, “die hard.” UFS is most commonly referred to as “moderate,” with connotations of “reasonable” and “willing to find compromise with management.”

My own belief is that it’s fair and accurate to use the term “militant” to describe Membership First, but the term must be well understood by the writer and the reader. “Militant” should not suggest “fanatical” or “irrational,” or “willfully stubborn” as many entertainment reporters imply when they speak of “militancy.” I mean “militant” in the traditional, historical, labor-movement sense of “willing to do what is necessary” to achieve fair wages, benefits and working conditions for the members of the union — with the democratic backing of the membership.

Further, my belief is that the faction known as Unite for Strength would be more accurately described, not as “moderate,” but as “non-militant,” implying a preference for “collegial” relations with management, avoiding “antagonism” or “confrontational postures.” (At times, I think, the term “anti-militant” would be more accurate.)

My attempt at semantic rigor about terminology comes down to a very basic question — to strike or not to strike.

And the attitude of the corporate show-business press is not forthright or neutral on that question. Which might explain the insinuations of irrationality and fanaticism applied to Membership First.

The “militants” are very clear that the only meaningful weapon any work force (including screen performers) has is to withhold its labor from the industry owned and managed by the members’ employers. The “non-militant” Unite for Strength seems to believe in the power of persuasion, in appeals to their employers’ sense of fair play. They believe in trying to reach a thorough understanding of the “legitimate” needs of their economic antagonists, who should not be seen as antagonists, but as “negotiating partners.”

If the non-militants can grasp the elements of their employers’ “business model,” if they can inhabit the employers’ mindset, they will better understand what their employers can comfortably grant in negotiations. And Unite for Strength will tailor their bargaining demands accordingly.

Viewing the factional differences from a different angle, from a class perspective, I would say that Unite for Strength’s most important and reliable constituency consists of the top 3% of wage earners in SAG-AFTRA. I believe they are also supported by some lower-wage earners who have confidence that they will someday join the ranks of the 3%.

In most SAG-AFTRA elections the turnout is well under 25% of eligible voters. Unite for Strength’s supporters know that their interests lie in maintaining the status quo. A strike would disrupt their income stream. They know where their interests lie and they can be counted on to return their ballots.

The successful character actor James Cromwell once told me, with striking candor, “We’re the one percent, David. We’re the ones who have the most to lose.” At that time, he clearly thought that I was among the “we.”

My personal assessment is that the individuals I know in Unite for Strength feel that they belong to an elite core of actors whose interests should take precedence over other actors whose talent and training, whose discipline and commitment, to “the craft,” are inferior. SAG-AFTRA’s resources should be used to serve, not all members, but those most deserving.

Unite for Strength versus Membership First. With these factional differences in mind, let’s look at the factual basis underlying the protests regarding the latest elections within SAG-AFTRA.

BUT FIRST: A WORD ABOUT VIOLATING THE TABOO

The man accused of election violations, Thomas Jeffrey Hanks, is held in the popular imagination as a beloved cultural icon; a treasured all-American banner-image, the embodiment of kindness and decency. When we think of Thomas J. Hanks, we think of “Tom,” the quintessentially nice guy.

There is a taboo, especially in the world-encompassing city-state of Hollywood, against disrespecting beloved icons. If the iconic individual also happens to be one of the most powerful corporate players in the industry, one should be especially wary. When you allege wrong-doing by such an imposing icon, you had better have a very strong case.

It’s dangerous to say it; it’s sacrilegious, almost blasphemous, but I believe something is amiss in the interactions of Thomas J. Hanks and the union party known as Unite for Strength.

This particular icon’s behavior seems incongruous, given his sterling imprint on the American mind. What seems even more surprising is that his conduct has been evident for many years. There is nothing controversial in the facts of the case. Those facts are not in dispute. The evidence is not hidden. In the case of Thomas J. Hanks, it has simply been overlooked, or purposefully ignored.

We’ll investigate, but we’ll tread carefully.

Front page of Unite for Strength election brochure/mailer. Scan Dave Clennon.

FAME, POPULARITY AND THE POWER OF THE ICON’S ENDORSEMENT

Labor unions are structured as democracies. Card-holding, dues-paying members vote for officers to lead their organization between elections.

A handful of candidates may run as independents in the biennial SAG-AFTRA elections, but most run on one or the other of two opposing slates chosen by Membership First and Unite for Strength.

Like most voters in most democratic elections, few members of SAG-AFTRA follow the week-to-week deliberations and decisions of their elected leaders. Very few members know every detail of every contract under which they work, or how those details were agreed upon in negotiations between their elected officials and their bosses. It’s difficult for the average voter to know which candidate or party best represents her values and her interests.

So, as in many other elections, most voters either abstain from voting or they rely upon the advice of other members.

We consult with friends of ours who are more engaged in our internal politics: Which candidate will do the best for us? Should I vote a straight ticket, or can I vote for somebody I like, on the other slate? Which slate of candidates will do the most for me and actors like me? Should I vote for this strike authorization? Should I vote to ratify this contract?

Should I vote to merge our union with that other performers’ union?

In addition to our friends, we put our trust in the advice of high-profile formal endorsers. Famous and very successful individuals like Thomas J. (“Tom”) Hanks.

Since I joined the Screen Actors Guild in 1972, I have never seen a celebrity endorsement in a union election that could match the value, the sheer weight, of an endorsement from Tom Hanks.

And the evidence is clear that Thomas J. Hanks wanted every voting member of SAG-AFTRA to see his photograph and to read his unequivocal endorsement of his political slate in 2021.

Since at least 2008, Tom Hanks has given his public endorsement in every union election. And he has never failed to endorse one specific party, Unite for Strength.

That is unethical. Why?

First let me be clear: I support Membership First. This year I ran, on the M1st slate, for the position of one of 129 L.A. delegates to the SAG-AFTRA biennial National Convention. Suppose Thomas J. Hanks had given his endorsement to me? I don’t think any observer would doubt that, instead of losing, by less than two-thirds of one percent of 13,732 votes, I would have strolled to an easy victory.

But it would have been unethical for Mr. Hanks to have given me his endorsement, and it would have been shamefully unethical for me to accept it. Why?

Because Mr. Hanks is an icon with a dual nature.

Yes, “Tom Hanks” holds membership in our union. But the man behind the man represented in the icon is one Thomas J. Hanks, known to the Secretary of State of California as the C.E.O., the Secretary, and a Member of the Board of Directors of PLAYTONE Company. Mr. Hanks co-founded PLAYTONE on January 23, 1998, in Santa Monica, CA, and he has grown it into one of the largest independent manufacturers of screen entertainment in our industry. Since its founding PLAYTONE has employed thousands, (probably tens of thousands) of actors. And PLAYTONE continues to employ actors to this day.

Thomas J. (“Tom”) Hanks is the very employer of the worker-voters he seeks to sway in an election that will have consequences for him and for the production company which he heads. Thomas J. Hanks, the producer-employer, weighs far more, economically, than Tom Hanks the beloved actor-icon.

The facts are not in dispute. Mr. Hanks has used his fame and his popularity to influence elections within the walls of the SAG citadel for at least thirteen years. There are rules and regulations and statutes and laws that seem to forbid the behavior Mr. Hanks has been engaging in all those years. The year 2021 was no exception.

The Election Committee which just ruled in his favor is dominated by Mr. Hanks’s party, Unite for Strength.

Since the Committee dismissed our complaint, we will have to ask the DOL’s Office of Labor-Management Standards to investigate the conduct of Mr. Hanks and of Unite for Strength.

As we prepare to take our case to the Department of Labor, let’s flash back to 2008, when I first became aware of Thomas J. Hanks as one of the designers and engineers of the Trojan Horse. From that vantage point I hope to establish motive, and to suggest the outlines of intent, knowledge, preparation, opportunity and execution on the part of Mr. Hanks and his associates.

MR. HANKS HAS A HISTORY — 2008

2021 was not the first time Mr. Hanks intervened in the internal politics of his union.

On November 5, 2007, the Writers’ Guild of America (WGA) voted to go out on strike. The most urgent issue was what were then called “New Media.” The writers saw clearly that the old gold mines of VHS tapes and DVDs would soon be abandoned for the new gold mine of Video-on-Demand, that mysterious, miraculous technology called “streaming.”

The industry owners and bosses wouldn’t even admit that there would very likely be huge veins of gold in that fresh mine.

The bosses were represented by the AMPTP, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, the entertainment industry’s official collective bargaining agency. The AMPTP has over 350 members, including studios and networks and independent producers. It is staffed by lawyers and accountants and it is built to research all the financial labyrinths of the industry. One of its key missions is to predict, privately, what future streams of revenue will bring into industry coffers. Future streams like “streaming.” It would be naive to believe the AMPTP when it declares, “We just don’t know what fruit these new technologies will bear — if any!”

The Writers’ Strike was — as most strikes are — a serious disruption in the lives of the Hollywood “community,” with plenty of reverberations throughout greater Los Angeles. But most writers were willing to make the sacrifice — and to take the heat and the fierce hostility of some in the industry — in order to win their demands for a share of the studios’ and distributors’ and producers’ New Media wealth.

In 2007, the elected leadership of the Screen Actors Guild had the old-time labor-solidarity spirit. The SAG leaders were comrades in the militant Membership First party. They knew that the Writers’ Guild’s fight for a share of New Media wealth was their struggle, too. President Alan Rosenberg and his allies were fiercely supportive of the writers. At just about every picket site, we actors could find signs on sticks — “Screen Actors Guild in Solidarity with Writers.”

The writers stayed on the line. The AMPTP stonewalled. The strike continued. Negotiations dragged on, through Christmas and past New Year’s of 2008. The Screen Actors Guild continued its vehement support of the writers.

Then, as the writers continued to walk the line, SAG began its own deliberations on what its members should demand in their own negotiations with the mogul-bosses, due to begin in six months. The most important deliberating body at that moment was the Wages and Working Conditions Committee, the W&W. That combination of volunteers and elected officials would discuss, debate, vote and, eventually, make recommendations to the National Board, which would then appoint a Negotiating Committee, and formulate a list of demands — carefully and strategically, without tipping its hand to the bosses.

During the early days of SAG’s W&W deliberations, on February 12, 2008, the Writers’ Guild strike ended — with small, but precedent-setting victories for the rank-and-file.

Two days later, Valentine’s Day, 2008, a strange thing happened.

Here’s an account from the New York Times, February 15, 2008:

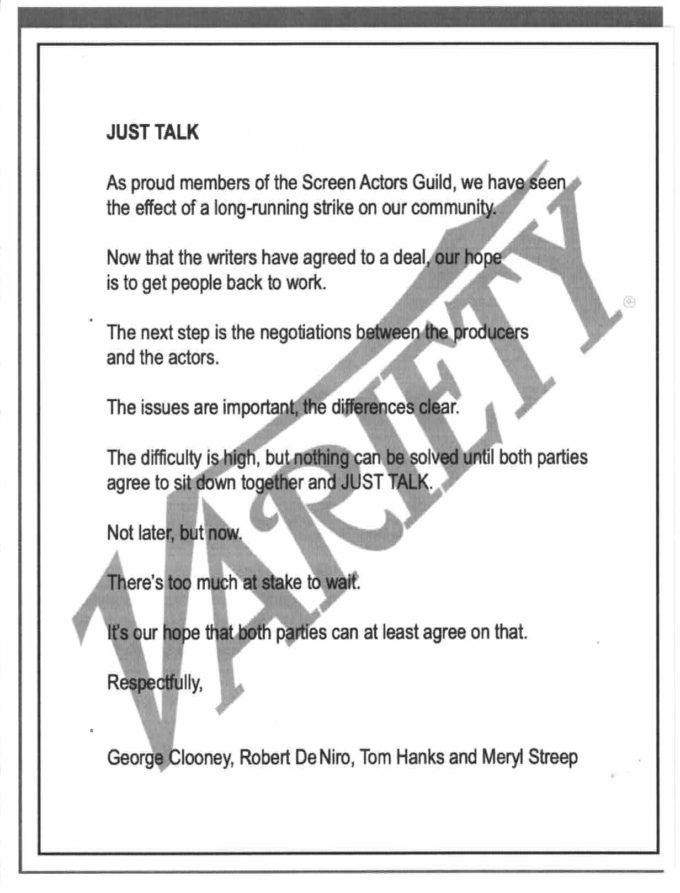

Apparently many in Hollywood have had their fill of labor discord. On Friday, Tom Hanks, George Clooney, Meryl Streep and Robert De Niro took out a full-page advertisement in Daily Variety, the industry trade paper, urging production companies and the actors organizations to “Just Talk.” “Not later, but now,” the ad read in part. “There’s too much at stake to wait.”

The actors’ contract expires on June 30, and to help avert a walkout, those boldface names want negotiators to begin their talks long before that deadline and not to wait, as had been expected.

“JUST TALK.” To an outsider, this request, from Thomas J. Hanks, and two of his fellow movie-star-producers, and from the grande dame of American cinema, must have seemed innocent. On its face, it was addressed to both of the antagonists in the coming (June 30) labor negotiations: SAG, the Screen Actors Guild, and the AMPTP, representing the actors’ bosses.

By choosing not to quote the headline of the ad in its original all-upper-case form — “JUST TALK” — the New York Times missed some nuance. Observers of the Hollywood labor scene would have known instantly that the rhetorical request was actually a command. A command from Hollywood royalty. The command was, in fact, addressed to only one of the antagonists, the union representing screen actors. Actually, the command was even more pointed: it was directed at Alan Rosenberg and

Doug Allen, the President and the National Executive Director of the union; it was also intended to be heard by the militant majority of the Screen Actors Guild’s National Board, which has the ultimate responsibility of approving contract agreements to be ratified by the membership.

Full-page ads in Variety are expensive. But the price (as much as $10,000) is pocket change for someone like Thomas J. Hanks.

That pricey ad was followed, ominously, the next day, by a free, prominently placed Letter to the Editor in another important show-business outlet, the Los Angeles Times. That message was signed by Thomas J. Hanks, using the pen name Tom Hanks, and by George Clooney, and it appeared on the Times’s prestigious Op-Ed page.

The two movie-star-producers delivered a message similar to “JUST TALK,” but with more rhetorical leisure and at no expense whatsoever to themselves.

Mr. Hanks and Mr. Clooney’s second gut-punch to their union, opportunity courtesy of LA Times op-ed page editor, Nicholas Goldberg.

Variety and the LA Times — that is a public relations double-whammy in Hollywood.

Those two media blasts were a one-two gut punch to the Screen Actors Guild.

Thomas J. Hanks and his associates knew exactly what they were doing. They were sabotaging the union’s lengthy, and democratic, process of preparing for negotiations, which were not supposed to begin for four and a half months. SAG’s Wages and Working Conditions Committee had barely begun its deliberations.

I posted a complaint on an unofficial actors’ bulletin board at a small online site, operated, without compensation, by actor Brian Hamilton. In my post, I scolded Hanks, Clooney, DeNiro and Streep for their disloyalty to the union. I was angry that this elite quartet would go over the heads of the members of their own union and publicly bully their elected leaders.

The next several months were consumed with political struggle and a series of defeats for SAG militants, including a grossly inadequate contract for the members (one which represented no improvement whatsoever upon the small advances in the Writers’ Guild contract).

I believed that much of the credit for the employers’ victory belonged to Thomas J. Hanks. Mr. Hanks, and his lieutenant, Mr. Clooney, had forced their own union, and its key leaders, Alan Rosenberg and Executive Director Doug Allen, into a defensive posture, vis-a-vis management, from which they never recovered.

In December of 2008, Mr. Hanks sent me a letter. (I’ll say more about the motivation for his letter in Episode 2.) In that letter, and in subsequent exchanges, Hanks revealed what I believe to be a key motive for his behavior toward our union. Here is an excerpt from his first letter (December 12, 2008):

***

You and I have been lucky actors–and I know full well I have been the luckier. I became an actor by being in the right place at the right time (Cleveland, Ohio — 1977) and gambled that I could make a living as a professional. In 1980 I was employed by one of the three existing networks for $5000 a week. [Mr. Hanks was hired to co-star in “Bosom Buddies” on ABC.]

You recall the Actors strike of 1980, which began before my job started. During that strike, my savings disappeared, my wife and kid returned to our hometown to live with family, and I took on $10,000 of debt. Though I did not understand the parameters of that strike, I was a SAG member and never considered crossing a line nor questioned Guild leadership. The WGA walked out the following year. Remember that?

(Preliminary comment: Mr Hanks has no legitimate claim of “confidentiality” over his correspondence with me. He did not approach me in good faith, and the public interest trumps whatever excuse he might claim for maintaining secrecy.)

Comment: “parameters” is a strange word choice (“I did not understand the parameters of that strike.…”) Does Mr. Hanks mean “union demands”? In any case, Mr. Hanks claims he went through considerable hardship because of the SAG strike. He does not explain why he never bothered to investigate, discuss, and try to “understand the parameters of that strike.” He simply asserts a pro forma loyalty to the Guild.

The 1980 actors’ strike (96 days) won all-important concessions from the moguls on home video (VHS tape) and cable TV residuals (royalties). Actors less fortunate than Mr. Hanks depend on that income to survive through the periods between jobs, periods that can last weeks or months. That is a brief sketch of “the parameters” of which Thomas J. Hanks professes ignorance.

Comment: When the strike ended, Mr. Hanks began to work, at wages of “$5,000 a week.” After taxes, and agents’ commissions (10%), and 1980-living expenses, how long would it take to repay a $10,000 debt? Ten weeks? Twenty?

From the beginning of his acting career, Mr. Hanks seems to have lacked an appreciation for the life experience of the average, working, non-starring actor. When his entrepreneurial drive took him to the next stage — movie and TV producer — did Thomas J. Hanks’s capacity for empathy grow or shrivel?

Comment: I may be alone, but I think I hear a note of resentful bitterness in Mr. Hanks’s words, “Remember that?” I believe Mr. Hanks has harbored rancor towards the Screen Actors Guild and the Writers Guild of America ever since his slightly bumpy career take-off in 1980-81. What I do not hear in Mr. Hanks’s rhetorical, “Remember that?” is the slightest bit of rancor towards the members of the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers. Did the greed and the intransigence of the AMPTP screen moguls have nothing to do with the actors’ and the writers’ decisions to go on strike? Did the moguls’ relentless stonewalling not help to prolong the work stoppages, which both lasted more than three months?

***

Excerpts from later letters from Mr. Hanks, I believe, give further indications of motive:

January 15, 2009 —

You [Clennon] said That I have literally, if unintentionally done harm to SAG members, their wives, husbands, and children. I feel it must be said that the SAG Commercial strike of 2000 did irreparable harm to those same actors and their families. The WGA strike of last year [2007-08] did even more. The improvements in those contracts came nowhere near balancing the losses wrought … by those strikes.

***

Again, I hear bitterness and resentment toward the actors’ and writers’ unions. In his letter to me of March 17, 2009, the sense of injury came into much sharper focus, as he recalled the SAG commercials strike of 2000:

My brother, [____], once made his living in commercials – among other gigs, he was the voice of Geoffrey the Giraffe for Toys R’ Us. . . .

My brother [____]’s career was wiped out during the strike and the fallout afterwards. Production Houses and agents he had done business with went bust. Accounts disappeared and were never replaced…. You suggest, “lost production was, gradually, made up.” Not according to my brother and literally all his friends who can no longer find work in commercials. (Not that the industry does not still exist. My youngest son threw a snowball in a commercial for Goodyear and now has money in the bank because of it.)

What are the motives for Mr. Hanks’s conduct in 2008 and in the 2021 SAG-AFTRA elections? (And all the years between — Episode 2). How to characterize the motive exposed in these excerpts (1980 & 2000)?

One human response to injury is to assign blame, and then to seek vengeance.

“Vengeance” may be too strong a word here. “Payback” is a better fit, I think. With these formative events in the life of Thomas J. Hanks, he seems to have been driven by a desire — not to “bust” his union — but to weaken it, to cripple it, to bring it under the control of reasonable men such as he. (Meanwhile, Mr. Hanks assigns no blame to the corporate moguls on his side of the negotiating table.)

Motives: payback and pre-emptive control.

With Tom Hanks’s invaluable endorsements, Unite for Strength won control of the Guild, and has maintained control, during the merger with AFTRA (2012), and up to the present day. As long as Mr. Hanks and his party rule SAG-AFTRA, the old-time militant spirit will be in deep freeze, if not dead.

And Thomas J. Hanks’s corporate agenda, his multi-million-dollar slates of films and TV shows, will never again be disrupted, as it was by the Writers’ Guild strike of 2007-08.

This is not a good time to write objectively about Thomas J. Hanks or his alter-ego, Tom. On August 29th, Ed Asner died in Tarzana, California.

Millions of fans are saddened by the loss of a beloved performer. But I am one of tens of thousands grieving the loss of the man, the political being, the dynamic agitator. Ed was my friend, my comrade. He was a knight, in battered, and very rusty, armor. He would have been offended, outraged, if you ever called him a Hollywood Liberal. Ed Asner was an American radical mensch. And he was deeply committed to advancing the labor movement.

To hold thoughts of Thomas J. Hanks and Ed Asner in the same moment puts Mr. Hanks at a definite disadvantage.

To be charitable, let’s say there are two versions of the Tom Hanks phenomenon. First, there is Tom, the kindly, unassuming, generous character you see on movie screens and in magazines and on talk shows. Then there is Thomas J. Hanks, Chief Executive Officer, Secretary and Director of PLAYTONE Company, State of California Corporate Number C2037162. That version of the Tom Hanks phenomenon is a mogul-boss, a man with little apparent sense of worker solidarity, a man of business with, seemingly, a vaporous ethical core. Thomas J. Hanks has functioned very efficiently behind the curtain of “Tom Hanks.” Who knows? Maybe Tom Hanks believes that he truly is that kindly, unassuming, generous character you see in the movies, or on your TV screens — on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, for example, celebrating President-elect Barack Obama, before his first Inauguration, in January 2009.

Ed Asner was one of the very last of a generation of actor-unionists who changed the Guild from a somewhat exclusive social club (“the Guild”) into a real labor union, one that didn’t just represent the highly successful one percent, but fought for all the members. Ed’s generation includes Sumi Haru, Bernie Casey, Yale Summers, Paul Napier, George Coe, Patty Duke Astin, Scott Wilson and Kent McCord, among many. Ed’s contemporaries had the courage, and the willingness to sacrifice, to win better contracts for all the members, present and future.

This article is accompanied by a photograph of Ed Asner at a SAG militants’ rally at Fox Studios in 2008. The picket sign Ed holds spells out a simple four-word message, “TOM HANKS UNION BUSTER.” In moral terms, that statement is true, but it lacks subtlety.

Thomas J. Hanks didn’t bust the Screen Actors Guild, in the sense of destroying it. He didn’t have to.

Mr. Hanks and his surgical team simply eviscerated our union. And they stitched up the wound and left the mummified exterior form, body standing up, skin still intact.

There is nothing controversial in the facts of this case. It could be seen as a sad sign of the endemic corruption inside the dream factory that no one has ever remarked upon it.* None of the trade papers, and definitely not the Los Angeles Times. The beloved icon has been engaging in his shady behavior in broad daylight. He may remind you of Jimmy Stewart in “It’s a Wonderful Life,” but you might also see strobe-flashes of Lionel Barrymore’s ruthless robber baron, Mr. Henry F. Potter.

BW0R95 SAG Activist Actors Protest Against FOX for Residuals from Online Reruns Ed Asner, with Sally Kirkland, Fox Studios, March 4, 2009. Photo credit: Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo. Provided to CounterPunch by Dave Clennon.

* The only accounts of this performers’ union corruption I’m aware of were two articles in CounterPunch, in 2011 and 2012, both by labor reporter David Macaray.