Photo: Friends of the Clearwater.

Clearcutting is an environmentally destructive but economically profitable way to log forests. Clearcutting and its related types of logging—i.e., seed tree and shelterwood cuts—remove most of the trees in an area and create what the Forest Service calls “openings.” This type of intensive logging emits carbon, eliminates carbon storage and carbon sequestration, and heats up our future. Clearcutting also fragments and impairs habitat for many wildlife, including sensitive species like fisher and wolverine, and threatened species like lynx. In sum, clearcutting primarily benefits the logging industry. While the science on clearcutting has evolved over the past four decades, the Forest Service’s culture for clearcutting and the policy intending to limit it has not.

Congress, through the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA), directed the US Forest Service to limit the acres opened from such intensive logging. The Forest Service set regulatory acreage limits depending upon region and tree species. For many places, including the Northern Region and national forests of Montana and northern Idaho, clearcut and related logging is limited to 40 acres per logging unit. NFMA allows exceptions to exceed this opening size, however. For example, a national forest manager may request that the regional office review and authorize logging-unit openings that will exceed NFMA’s limit. For ease of reference, this report calls these larger openings “supersized clearcuts.”

Friends of the Clearwater (FOC) investigated how often the Forest Service invoked this particular exception. Through a Freedom of Information Act request, FOC asked four regional offices (Regions 1, 3, 4, and 6) for requests received from 2013 until March of 2021 (the date of our FOIA request) where national forest managers requested that the regional office grant exceptions for supersized clearcuts. FOC also asked for the regional office’s response. Regions 3, 4, and 6 disclosed that they could not find supersized clearcut requests from national forests within their jurisdiction during this time period and thus did not authorize exceptions. Region 1, the Northern Region, stood out remarkably.

Above graphic: US Forest Service.

Between January of 2013 and March of 2021, the Northern Region disclosed that it received 87 requests from managers of national forests in its jurisdiction for permission to authorize supersized clearcuts. Out of the 87 requests, the Northern Region approved 79. The other eight requests were pending at the regional office at the time of the FOIA request. Notably, the Northern Region did not deny one single request for any supersized clearcut during that time period. Supersized clearcuts were sometimes approved for inventoried roadless areas and old growth, and projects approved with minimal environmental analyses.

This ceremonial, pro forma request-and-approve routine has impacted national forests of the Northern Region on a large scale. From 2013 until March of 2021, the Northern Region has approved 93,056 acres of supersized clearcuts, about twice the size of the District of Columbia. If the acres were arranged contiguously in a square, a person with an average walking speed of three miles per hour would have to walk two full eight-hour days just to traverse its perimeter.

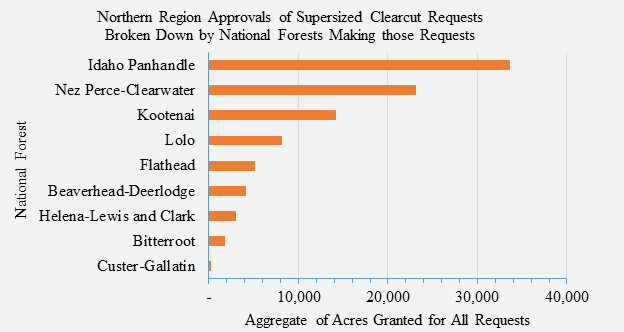

This acreage only represents supersized clearcuts; because many of the same projects planned openings under 40 acres, the landscape impacts from clearcutting and related logging is greater than the acreage presented here. Managers of the Idaho Panhandle National Forests and the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forests in Idaho requested over half of this acreage, at 33,625 and 23,095 aggregate acres. The Kootenai, the Lolo, and the Flathead national forests followed, in that order, for supersized clearcuts requested, which the Northern Region subsequently approved.

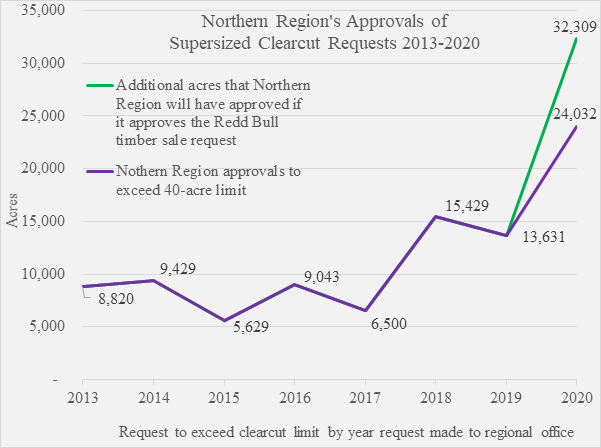

Alarmingly, the national forests managers’ requests for supersized clearcuts and the Northern Region’s rubber-stamp approvals have increased in recent years. From 2013 until 2017, the Northern Region granted requests that totaled between 5,500 and 9,430 acres. From 2018 through 2020, however, supersized requests and approvals in the Northern Region jumped to a new range, between 13,631 and 24,032 acres per year. More timber projects with supersized clearcuts and more supersized clearcuts per project likely accounted for the overall increase.

While the Forest Service has touted that its review process for supersized clearcuts involves the public, public engagement is neither logistically straightforward nor meaningful. Public notice—required for requesting a supersized clearcut—is broken up amongst several public comment periods, the later periods commonly restricting those who may participate and what they may say. Even if a comment is successfully made, it is received by the national forest managers who made the request, not to the higher-level officials reviewing it. This amounts to a “comments welcome” box for public involvement that is effectively a trash bin. Instead, the public’s only recourse to try limiting excessive, supersized clearcuts is with lawsuits brought under environmental laws that might offer a check on such intensive and large-scale logging.

National forest managers’ requests to exceed NFMA limits contained little meaningful justification as to why supersized clearcuts were necessary. We sampled justifications supporting supersized-clearcut requests during this period, justifications were indistinguishable from the general rationale underlying those timber projects. Requests from different projects across various forests often shared the same rationale. The common agency position was that natural disturbances are quite large, so clearcut disturbances should be as well. While convenient for large-scale logging, this is unsound logic.

An aerial view of an irregular shelterwood cut. Photo: Alpha 1.

No natural ecological disturbance exists in the Northern Region where dead trees disappear from the forest. Science demonstrates that biodiversity depends upon standing “snag forests” of dead trees as well as fallen dead trees. These trees provide structural habitat for wildlife—dens and nests—and dead trees are consumed by organisms that become food sources for other organisms. Clearcut trees hauled away, on the other hand, provide none of these ecological services. Also, the location or the genetics of a tree can contribute to survival during a large-scale ecological disturbance and a better, more heterogenous regeneration after a disturbance. While natural ecological disturbances can selectively remove vulnerable trees, clearcuts remove all trees, including those that might have otherwise survived. So, natural ecological disturbances renew forests better than the Forest Service’s clearcut disturbances do.

Ground-level view of the same clearcut, a year later after a prescribed burn. Photo: Friends of the Clearwater.

Despite common belief, there is no effective regulatory limit for clearcuts on the national forests in the US Forest Service’s Northern Region. Our investigation revealed a Forest Service region where especially large clearcuts are no longer the exception—they are the rule. The NFMA limit on supersized clearcuts, once meant to safeguard against on-the-ground misjudgments or excesses of zeal, is so routinely circumvented in the Northern Region that it no longer appears to accomplish either function. We anticipate that this overzealous and now routine circumvention will continue in the Northern Region, and supersized clearcuts will likely continue expanding in the national forests there until the national Forest Service leadership, the Biden Administration, or Congress intervenes.