Industrial agribusiness has been a scourge on our environment and communities. We’ve long and rightly celebrated the immigrants and workers who stood up to the corporations who colonized our richest farmlands throughout the United States.

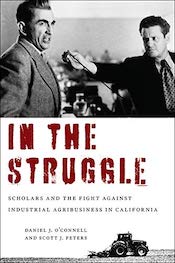

Yet, some of us may be surprised to learn that scholars also have a long history of taking on industrial agribusiness, especially in California. In our new book, In the Struggle: Scholars and the Fight Against Industrial Agribusiness in California, we profile eight scholars who were both researchers and activists and who saw the two as inseparable.”

Their work focused on California’s Central Valley, the site where some of the fiercest battles against corporate encroachment onto the land took place. One of them, Ernesto Galarza, was born on August 15, 1905, and he sets the model for activist scholarship as we continue the fight against land monopolies and economic concentration that threaten all rural communities and our broader democracy.

Born in Mexico in 1905, Galarza moved with his family to the United States when revolution convulsed his homeland. As a child, he worked as a hop picker near Sacramento. At that time, he recalled, “I became a leader of the Mexican community at the age of eight for the simple reason that I knew perhaps two dozen words of English.” He took jobs as a newsboy, cannery and packing shed laborer, social work aide, interpreter, Boys Club organizer, elementary school teacher, co-director of a progressive elementary school and education specialist with the Pan American Union.

Galarza received a B.A. from Occidental College, an M.A. from Stanford University, and a Ph.D. from Columbia University. He taught at a number of prestigious universities, including the John Marshall Schoolof Law, University of Denver, Claremont University, University of Notre Dame, San Jose State University, UC San Diego, UC Santa Cruz, and the Harvard Graduate School of Education. In 1979, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

This journey was long considered, a diligent and earned preparation for public service to his Mexican community in the United States. Galarza’s return to California as a farm labor organizer, after he finished his Ph.D. at Columbia, was the most intense application of that commitment.

Rather than parley his Ivy League degree into an academic career, Galarza set out on this task of resolving the “living and working conditions” of farmworkers by taking a position with the National Farm Labor Union. Between 1947 and 1959, Galarza worked as the  Director of Research and Education for the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU), later re- constituted as the National Agricultural Workers Union (NAWU), both affiliated with the AFL-CIO. This effort to confront and organize farmworkers laboring within California’s system of industrial agriculture arose as an outgrowth from the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU).

Director of Research and Education for the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU), later re- constituted as the National Agricultural Workers Union (NAWU), both affiliated with the AFL-CIO. This effort to confront and organize farmworkers laboring within California’s system of industrial agriculture arose as an outgrowth from the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU).

The STFU were a tough, nonviolent, and bi-racial union that recognized all classes of land workers, including day laborers, tenants, share- croppers, and small farmers. Forged in the crucible of Southern planter reaction, where they faced extreme violence and waves of systematic terror, the STFU were steeled to face California’s agribusinesses. The union, under the banner of the NFLU, entered the fields in 1947.

Galarza led the way, noting later that he participated in “probably twenty strikes,” mostly in California but also in Florida, Texas, and Arizona. From his position in the fields with the workers, he not only led strikes against particular farming operations but studied the broader, strategic issues and policy impediments facing farmworkers in California. His strategy involved attacking the “alliance” between agribusiness and government bureaucracies while introducing innovative approaches to labor organizing in the fields. With only a modicum of union support and financial backing, Galarza battled agribusiness for over a decade.

By standing on the ground and looking up through legal and political structures that hindered the farm labor movement, he identified specific objects for political engagement, most notably the DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation and Public Law 78, the authorizing legislation for the Braceros program. Both were audacious targets. DiGiorgio was the nation’s foremost vertically integrated agribusiness, marshaling enormous political influence, while the Braceros program was a federally supported, international farm labor infrastructure funneling workers to the United States from Mexico. The exploitation of these bi-national laborers subsidized agribusiness profitability versus family farms and undermined farmworker union organizing in California and across the country.

Galarza used his position and role as a scholar to battle the power elite of California. He took it upon himself to map, in fine detail, the industry he was organizing against. His research was enhanced by his close proximity to the problem. Social theories and scientific methods enabled him to see the structures he assaulted.

Books were at the center of Galarza’s politically engaged scholarship and corresponding organizing strategies.

Strangers in Our Fields (1956), more pamphlet than book, had the educational and political purpose of undermining Public Law 78. The book documented this law’s extensive problems by using accessible language, graphic photographs, simple statistics, and direct quotes from the braceros themselves. Its approach was reminiscent of Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor’s book American Exodus, as it had an explicit purpose to influence public policy. Galarza later admitted that the book was purposely provocative: “Presented with the experiences of the braceros in their own language, it was possible that the growers and government agencies would elect to challenge the material and thus bring the issue into the open.” As he was prone to do, Galarza baited his adversaries into overreacting.

As planned, the publication of Strangers in Our Fields instigated intense industry blowback. A resolution by the California State Board of Agriculture made numerous charges that it contained statements that were “derogatory,” “unfounded,” “inaccurate,” “untrue, disparaging, or otherwise damaging,” “erroneous and unjustifiably unfavorable,” and that the report was published “without independent investigation and evaluation of the reliability of the research methods and statements of findings, or of possible motives for bias.” An October 1, 1956 letter from the San Diego County Farmers, Inc. found:

The pamphlet entitled “Strangers in our Fields” by Ernesto Galarza, made possible through a grant-in-aid from The Fund for the Republic (Ford Foundation) contains a vicious group of false insinuations, and accusations. Its author, Ernesto Galarza, is well known in California for his active participation and leadership in creating labor disputes and social unrest. The convictions, and inferences recorded in this publication signify the author’s contempt for the honest efforts of faithful representatives of the U.S. and Mexico governments. It appears to be a biased, prejudiced, one- sided opinion by one whose interest and leanings could be questioned.

Agribusiness representatives tried to impugn Galarza’s integrity and his research. Rarely in his life did he allow such a challenge to go unanswered. Due to this backlash, the Department of Labor refused to publish the report. The U.S. section of the Joint United States-Mexico Trade Union Committee, which did publish it, agreed to investigate any discrepancies within the research. It later found no need for substantial revisions or corrections. Galarza responded in the second edition’s preface:

We remind those who previously denounced “Strangers in our Fields” and attempted to suppress it, that truth thrives on controversy and that mere denunciation never altered a fact. Censorship in a democracy is never called for except by those who fear the truth. On behalf of the trade union movement in both the United States and Mexico we pledge that organized labor will never cease its efforts in this area until abuses and exploitation of these Mexican workers as reported in this pamphlet are ended.

The goal of eliciting a challenge, of baiting agribusiness and its allies, had been successful. The straightforward booklet is a comprehensive, personalized account of the Bracero program’s effects. It situates the voice and perspective of farmworkers out front, while its chapters offer a view into the daily life of the bracero’s bureaucratized lives, smothering counterarguments in a barrage of detailed, first-person stories. Workers’ grievances included dilapidated housing; insufficient wages, or outright theft of wages; over-supplying labor markets, causing depressed wages; overcharging for substandard food; inaccurate record keeping and inappropriate pay deductions; unsafe transportation; health insurance premium deductions for inadequate or non-existent coverage; use of the farm labor padrone system; lax enforcement of program regulations; and poor worker representation at all institutional levels.

The braceros were inherently vulnerable and exploitable within this labor system. One said, “These things have to be tolerated in silence because there is no one to defend our guarantees. In a strange country you feel timid—like a chicken in another rooster’s yard.” Perhaps unknown to these workers, Galarza and his union were attempting to fill this role, starting by compiling documentary evidence and publishing the empirical findings.

A four-month survey enabled Galarza to collect first-hand accounts from braceros. He visited camps and worksites where he conducted interviews. Photographs emphasized his descriptions of housing and living conditions. Strangers in Our Fields begins with a Mexican farmworker saying, “In this camp we have no names. We are called only by numbers.” From this statement, Galarza proceeds to ethnographically document the conditions of the braceros experience in the United States spanning the transborder recruitment and migration from Mexican villages to work conditions in the fields.

The book remains close to its research subjects and readers, who are placed in the fields and work camps through his descriptions. From this first inflammatory account, Galarza followed with increasingly analytic scholarship.

Congress terminated Public Law 78, ending the Bracero program, on May 29, 1963 With subsidized braceros labor (used at times as strikebreakers, negatively affecting overall working conditions) purged from the labor market, the United Farm Workers union found traction and collective bargaining success immediately upon the defeat of Public Law 78, vindicating Galarza’s strategy and objective.

Galarza held no misconceptions of the system’s fairness, nor doubts of his opponent’s strengths. Methodically, he spent years in preparation for battle. As industrial agribusiness continues to lay waste to the economic vitality of rural communities in California and beyond and its hand in the environmental crisis becomes ever clearer, we would do well to remember the man born 117 years ago who may be the model for work still before us—particularly in new battlegrounds across the Sunbelt and Midwestern United States.

Adapted from In the Struggle: Scholars and the Fight Against Industrial Agribusiness in California.