Large blazes like the Camp Fire which leveled this McDonald’s in Paradise CA are driven by extreme fire weather, particularly wind. Active forest management including thinning and prescribe fire does nothing to prevent such blazes. Photo George Wuerthner.

Recently California Governor Newsom came out with a proposed fire budget of over a billon dollars. Unfortunately, like so many politicians, his budget emphasizes “active forest management” which includes thinning and prescribe fire to reduce the presumed “excess fuels” on public lands.

One can forgive Governor Newsom for his budget emphasis as he is likely depending on CAL Fire and the US Forest Service for his fire information. These bureaucracies see firefighting and fire “prevention” as a way to justify their existence and grow their budgets.

Most wildfires result in a mosaic pattern of charred and unburned patches as seen here in the 257,000 acre Rim Fire that charred lands near Yosemite NP, CA. An important observation is large areas of the Rim Fire occurred at high-severity fire even in fuels-reduced forests with restored fire regimes. Photo George Wuerthner.

A consistent theme of thinning and prescribed fire advocates is that such “active forest management” will preclude wildfires that are threatening communities. Active forest management including thinning and prescribed burns may make people feel good, but it is largely ineffective in protecting communities.

What drives all large blazes are specific weather conditions that include drought, high temperatures, low humidity, and most importantly, wind. If you do not have such extreme fire weather conditions, you will not get a large fire. Indeed, most of all, wildfires self-extinguish because the weather conditions are not conducive to spread.

That is an important qualifier. The majority of all fires never grow large, no matter how much fuel may be found on the site if the weather conditions are not conducive for fire spread. There is ample evidence that most fires remain small whether they are “suppressed” or not.

Of 235 backcountry blazes in Yellowstone between 1972 and 1987, all went out without suppression. Photo George Wuerthner.

A study in Yellowstone National Park between 1972 and 1987 allowed 235 backcountry fires to burn without suppression. Of these blazes, 222 never got larger than 5 acres, and most were an acre or less. And all 235 self-extinguished without any suppression efforts.

Another review of wildfire in the Rocky Mountains found that between 1980-2003, a total of 56,320 fires burned over 9 million acres. About 98% of these fires (55,220) burned less than 500 acres and accounted for 4% of the total area burned. By contrast, 2% of all fires accounted for 96% of the acreage burned. And 0.1% (50) of blazes were responsible for half of the acres charred.

The 280,000 acre Thomas Fire by Santa Barbara is typical of many blazes in California in that it burned primarily in chaparral which “active forest management” won’t influence. Photo George Wuerthner.

Even in a major fire year such as 2020, where more than 4 million acres burned in California alone, the majority of all acreage charred was due to a few blazes. Only five fire complexes out of over 9,600 fires across California (approximately 0.05%) accounted for nearly 82% of the structures destroyed or damaged across the state that year. Furthermore, about 0.2% of all fires in California last year accounted for about 84% of the total burned acreage in the state.

Such statistics point out the critical point that nearly all wildfires are insignificant. They don’t “destroy” forests or homes. They remain small because without the proper fire weather conditions, ignitions will not spread, and the majority sputter out.

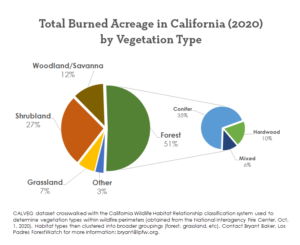

These statistics also demonstrate that thinning/logging is ineffective in controlling the very fires threatening human communities. Moreover, in California, about half of the blazes were in chaparral, savanna woodlands, or grasslands, not in forests where thinning is advocated.

Even in forested stands, the percentage of fires that occurred in forests, blazes in conifer stands accounted for 35% of all acreage.

The 2020 North Fire Complex, California’s largest blaze in 2020, burned 318,000 acres, mainly in a mixed-conifer forest in the northern Sierra. Much of the area was commercial timberland that had been clearcut within the last couple of decades. The rest of the acreage charred was on USFS land in the Plumas National Forest.

The North Fire burned through large areas that had been commercially and non-commercially thinned, burned, or otherwise managed. It also burned through some extensive regions that had experienced fire back in 2008.

California’s largest fires in recent years—including the Creek Fire and August Complex in 2020 and the Camp Fire in 2018—burned through large vegetation management project areas in national forests and on private or state lands.

None of these “fuel reductions” stopped the blazes. And worse for communities, a number of studies have found that “treated” lands burn with higher severity than natural landscapes.

Thinned forest and clearcut (in the background) near Chester, California. Logging or what is termed “active forest management” may make people feel good, but such efforts seldom preclude large blazes that always driven by extreme fire weather. Photo George Wuerthner.

All of this suggests that the emphasis on “active forest management,” whether prescribed burns or thinning, does not work on the very fires we hope to contain. Indeed, there is evidence that logging/thinning can enhance fire spread by opening up the forest to greater drying and wind penetration.

California Governor Newsom’s billion-dollar fire budget priorities are backward. It provides less than 4% of those funds for “community hardening.” An effective fire strategy would include a massive reduction in logging/thinning and a much greater emphasis on creating homes and communities that can survive a fire.