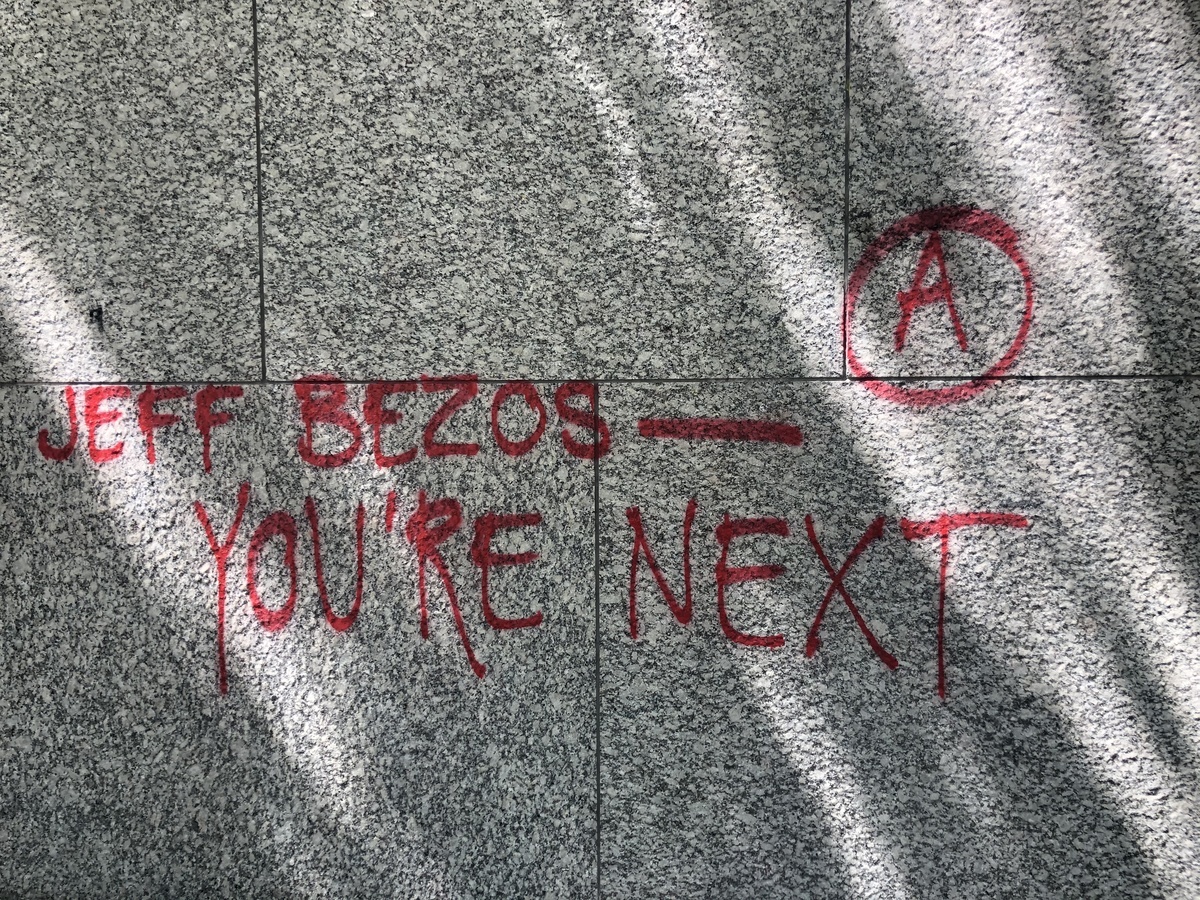

Graffiti in Portland. Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair.

On Friday, April 9, the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union was defeated in its effort to organize Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, AL. The union accuses Amazon of unfairly interfering with the vote and plans to appeal.

However disappointing is the Amazon defeat, it signals something more telling. During the fin de siècle and the early-20th century, large corporations cornered whole segments of America’s economy using predatory pricing, exclusivity deals and other anti-competitive practices to undercut smaller local businesses. And numerous strikes were defeated, often leading striking workers injured, arrested or killed.

After the economic panic of 1893, a growing number of Americans questioned the capitalist system. Between 1897 and 1904, a total of 4,227 firms merged to form 257 corporations. The largest merger combined nine steel companies to create U.S. Steel. By 1904, some 318 companies controlled nearly 40 percent of the nation’s manufacturing output. A single firm produced over half the output in 78 industries. These corporations became known as “trusts” – and they have returned with a vengeance.

***

U.S. capitalism has come full cycle over the last century. The earlier development of the trust-dominated economy fueled the rise of the Progressive era and what Teddy Roosevelt dubbed “muck-rakers,” journalist who investigated and publicized social and economic injustices. They included Jacob Riis, Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell and Ida B. Wells. Progressives sought to elimination of government corruption, supported women’s suffrage, championed social welfare, prison reform, civil liberties and prohibition. Some supported civil rights, even backing the formation of the National Association for the Advancement for Colored People (NAACP).

In particular, many Progressives feared that concentrated, uncontrolled, corporate power threatened democratic government. They argued that large corporations could impose monopolistic prices to cheat consumers and squash small independent companies. And these trusts could control both federal and state governments.

This furor led to adoption of the Sherman Act of 1890. It outlawed “every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy in restraint of trade.” The Sherman Act also made it a crime “to combine or conspire . . . to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several states.” While of limited effect, it did establish the federal government’s ability to control corporate consolidation and power.

On a second front, between 1909-1913, 28 states established regulatory commissions or gave existing railroad commissions jurisdiction over telephone companies. In addition, 1907-1913; in addition, between 1907-1913, 26 staters passed laws authorizing some form of compulsory physical connection between telephone companies. In 1910 the Interstate Commerce Commission was given the authority to regulate telephone companies as common carriers.

***

Teddy Roosevelt distinguished between “good trusts” and “bad trusts,” with “bad” defined by irresponsible corporate practices. He championed the regulation of “bad” corporations in the public interest by means of government commissions.

During the early 20th century, there was much debate as to the difference between a “trust” and a “cartel.” In 1910, the Marxist economist Rudolf Hilferding published Finance Capital that offers the following distinction:

The trust has an advantage over the cartel in fixing prices. The cartel is obliged to base its fixed price on the price of production of the most expensive producer among its member firms, whereas for the trust there is only one uniform price of production in which the costs of the more efficient and less efficient concerns are averaged out. The trust can set a price which allows it to maximize its output and make up for its small profit per unit by the volume of its turnover. Furthermore, the trust can close down the less profitable concerns much more easily than can the cartel.

However, he notes, “the cartel form of organization can limit the independence of the participating enterprises to such a degree that it becomes practically indistinguishable from a trust.”

Standard Oil had, by 1880, acquired about 100 independent oil refineries, thus controlling about 90 percent of the U.S. oil business. In 1882, Rockefeller formed the Standard Oil Trust as a way to conceal Standard Oil as a monopoly. Railroad companies, cigarette makers and sugar refineries, among others, followed suit and organized their own trusts.

Roosevelt’s Justice Department launched 44 anti-trust suits, prosecuting railroad, beef, oil and tobacco trusts. Henry Clay Frick, the steel baron complained, “We bought the son of a bitch and then he didn’t stay bought.”

In 1902, the nationwide call for “trustbusting” led TR’s Justice Dept. to file suit under the Sherman Act against the biggest railroad trust in the country, J.P. Morgan’s Northern Securities Company.

In 1904, the Supreme Court ruled against Northern. In a stunning opinion, Justice John Marshall Harlan declared that “every combination” (aka trust) that eliminates interstate competition was illegal. The court included combinations of manufacturing companies and railroads. The Court found that all monopolies tended to restrain trade and “to deprive the public of the advantages that flow from free competition.” The Court ordered the breakup of the Northern Securities into independent competitive railroads.

The most famous anti-trust suit was filed in 1907 against Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company because it – and its subsidiaries — controlled 85 percent of the market. Justice Department investigators uncovered secret rebates the company received from railroads and concluded that Standard Oil held “monopolistic control . . . from the well of the producer to the door step of the consumer.” It took the government five years to win the case in the Supreme Court and, in the end, Standard Oil was broken into 34 separate companies; among the new companies were Chevron, ConocoPhillips and Exxon Mobil.

The following year, the federal government filed a Sherman antitrust suit against the American Tobacco Company that controlled almost 90 percent of U.S. cigarette, snuff, chewing and pipe tobacco sales. Like Standard Oil, American Tobacco had acquired over 200 competitors, often selling cigarettes below cost in order to bankrupt competitors.

The trusts led to innumerable mergers and eliminated competition among their members. They also concentrated control of national wealth in the hands of a few robber barons, millionaires like Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Henry Ford and Andrew Carnegie.

***

When the Standard Oil Trust was formed in 1882, it produced most of the world’s lamp kerosene, owned 4,000 miles of pipelines and employed 100,000 workers. Rockefeller owned one-third of Standard Oil’s stock worth about $20 million (the equivalent of $557 million in 2021 dollars) and – like some robber barons today — often paid above-average wages to his employees, but he strongly opposed any attempt by them to join labor unions.

The era of the trusts, of Progressive politics and journalism, was also an era of many – and often very violent – strikes and labor protest, most of which the workers and activists lost. Among some of the most noteworthy strikes of the pre-WW-I era are:

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 – precipitated because wages to the B&O railroad workers were severely cut; workers shut down railroads in Pennsylvania and West Virginia for a week.

Haymarket Riot of 1886 – occurred amidst a Chicago labor rally when someone threw an explosive at the police, sparking a riot that led to the deaths of eight people; a subsequent trial led to the seven labor activists sentenced to death and one to a term of 15 years in prison.

Homestead Strike of 1892 – workers at this Carnegie steel plant revolted over harsh conditions and poor pay, and the company brought in strikebreaker and Pinkerton agents to suppress it; a gun battle resulted with the deaths of a number of strikers and agents.

Pullman Strike of 1894 – Pullman railroad workers struck during a severe economic depression that disrupted rail traffic in the Midwest; it marked the first time a federal government injunction was used to break astrike.

Coal Strike of 1902 – 145,000 United Mine Workers of America in the anthracite coalfields of eastern Pennsylvania struck for about 5 months for higher wages, shorter workdays and union representation; the miners won, receiving a 10 per wage increase and reduced workdays from ten to nine hours.

Bread and Roses strike of 1912 – after a new state law had reduced the maximum workweek from 56 to 54 hours, factory owners responded by speeding up production and cutting workers’ pay; 10,000 immigrant mill workers struck – backed by the IWW — and, following public Congressional hearings, the workers won, getting 15-percent wage hike, an increase in overtime pay a promise not to retaliated against.

Paterson Silk Strike of 1913 – 25,000 silk workers shut down the 300 silk mills and dye houses in Paterson, NJ, for almost five months, but were eventually defeated; the workers struck over demands for an 8-hour work day and improved working conditions and, led by the IWW, 1,850 strikers were arrested and jailed.

Ludlow Massacre of 1914 – a organizing campaign of 11,000 coal miners by the United Mine Workers at the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron Company turned violent when the miners were violently attacked by Colorado National Guard and company guards; the attack left 25 people dead, including 11 children.

Bayonne Refinery Strikes of 1915 and 1916 – about 1,200 refinery workers at Standard Oil of New Jersey’s plant and the Tidewater Refinery on Constable Hook, Bayonne, NJ, struck over demands for increased pay and better working conditions; during the two strikes, 4 people were killed and 86 wounded, and the results were mixed with some pay gains in 1915 strike, but nothing was gained in 1916.

A century later, everything and nothing seem to have changed. Trusts are back with a vengeance. A century ago, radicals battled the shameless practices of industrial trusts like Standard Oil, American Tobacco and Northern Securities who have morphed into their corporate descendants, be it Amazon, Facebook, Google or AT&T and Comcast. This time, unfortunately, there is no TR to do battle for the public good.

Yesterday’s millionaires have become today’s billionaires. Rockefeller, Vanderbilt, Ford and Andrew Carnegie have morphed into Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos.

For all the inside the Beltway talk about breaking up the 21st century trust, little is likely to happen – at least for now. Democrats and Republicans — along with a vast infrastructure of lobbyists, front groups, grateful nonprofits and astroturf shills — shamelessly serve the interests of not only big finance, but big healthcare, big energy and big telecom. Political support for consolidation is rationalized as necessary to combat the challenge of globalization and to ensure American competitiveness, fictions waved before the electorate every other year to inflame patriotic zeal.

And workers keep getting screwed – and, like the Amazon workers, union organizing efforts defeated. But like the unexpected outcome of the restructuring of corporate capitalism that came in the wake of the Great Depression and WW-II, the deepening crisis of U.S. and global capitalism may usher in a new era of worker empowerment. One can hope – and organize!