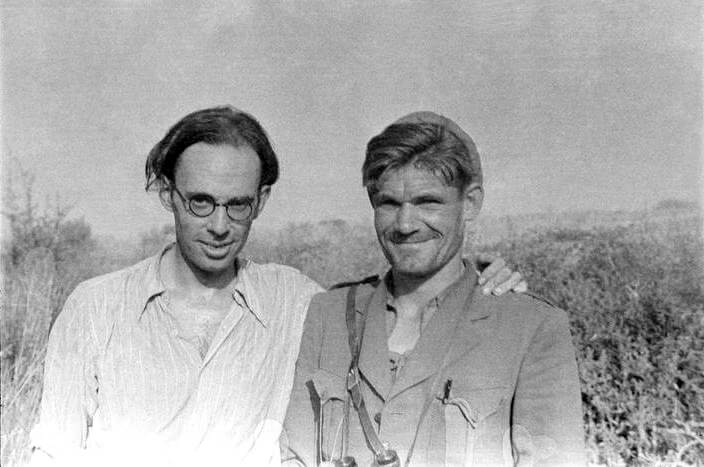

Claud Cockburn on the left. Unknown author. Public Domain.

Claud Cockburn —father of Alexander, Andrew, and Patrick, three brilliant journalists— was the original model. In 1967 his three volumes of autobiography were consolidated and published by Penguin as I, Claud… It’s hard to find a copy these days, so I’ll quote up to the legal limit.

Claud Cockburn was born in Peking (now Beijing) in 1904. His father, “a younger son of Lord Cockburn, the great Scottish advocate and judge who shone so brightly in the golden age of Edinburgh society,” had passed the necessary exam at age 19 and become British Vice-Consul in “the then-remote city of Chungking…

At the time it was forbidden for foreigners to reside in or even visit that part of Chungking on the right bank of the Yangtze. Righty, the Chinese believe that if you give the foreigners an inch they will take an ell. Once a month my father —designing to establish precedents and break down this ban— used to send a formal notification to the governor, who resided on the right bank, that the British Vice-Consul proposed to call on him on a certain date. The governor, not wishing to make a formal breach of relations, always acceded. On the day fixed, my father was transported across the river, and was met on the opposite bank by the governor’s litter, with a heavy guard of soldiers. The steep street to the governor’s residence were lined with furiously hostile crowds their natural hatred of the intruder encouraged and stimulated when necessary by agents of the governor. They pelted the litter with stones. Every couple of hundred yards the litter was halted while the soldiers battled with the populace.

At the governor’s residence the governor entertained the vice-consul and they talked for a couple of hours. At some point during the conversation, the vice-consul took occasion to remark with satisfaction that it was now evidently the policy of the Imperial Government to permit an Englishman to visit the right bank of the river at Chungking. At some other point the governor would take occasion to express his satisfaction that in this single instance it had been possible for the Imperial authorities to suspend for a few hours the inviolable rule against the presence of foreigners on the right back, and that the efficiency of the troops had sufficed to curb, on this particular day, the profound indignation of the people.

The parting ceremony was also a somewhat elaborate maneuver, it being necessary for the vice-consul to take his leave in words carrying the general sense of au revoir, whereas the governor must give to his courteous parting remarks the unmistakable nuance of an adieu. Then came the progress back to the river, with stoning, battles, and occasional bloodshed.

Claud was educated in England with an interlude in Budapest, where his father was posted for three years. “The valley of the Danube was the first area in which I ever felt immediately and completely at home,” he writes. “Since then I have twice experienced the same sense of being immediately at home in an entirely strange place —once in New York and once in Oklahoma City.”

He won a scholarship to Oxford, then a fellowship that would support him for two years. Journalism, deemed unclassy in Academe, was his chosen profession. He headed for Berlin with a letter of introduction to the Times of London bureau chief. His supposed connection was gone, but the new chief, Norman Ebbutt, was short-handed, put Cockburn to work, and introduced him to his sources. “Norman Ebbutt was intelligent and courageous,” Cockburn writes, “and he needed to be, for he was a man of goodwill… Politically he was, I suppose, what could be described as a Left Wing Liberal, which meant, at any rate in his case, that he hoped for the best in everyone.”

For a while Cockburn wrote articles that the Times ran but wouldn’t pay for. Then they paid him as a free-lancer. Then, at Ebbutt’s urging, the London office offered to hire Cockburn; but this would have entailed moving up a career ladder in England before he could be a foreign correspondent —the job he wanted and already had— so he declined. People at the Times’ London office were reportedly, “shocked but rather pleased. For years nobody had actually refused a job on the Times: they thought this showed originality.”

Then Cockburn broke a big story. “Towards the end of a blazing afternoon,” he recounts, “tornadoes of rain rushed suddenly down on Berlin, and there were reports of a cloudburst on the borders of southern Saxony. The reports in the evening papers had that curious smell about them which suggests immediately that somebody somewhere is trying to conceal something.”

Cockburn caught a train “At my own expense —an alarming speculation. I got there at dawn, observed with satisfaction that there were no other journalists about, and found that, in one of the strangest small-scale catastrophes of the decade, the cloudburst had poured unheard of quantities of water into little mountain streams, which tore down trees formerly  far above their beds, jammed the broken trees against the bridges until they formed high timber dams, and, pushed harder than ever by the dams, rose and rushed along the streets of sleeping villages on the valley side, peeling off the front of houses like wet cardboard, and killing more than 100 people in a few minutes. Half a mile of that little valley smelled of death. There were corpses in the mud and in one house the table in an upper back room had been late for breakfast. In several other houses canaries were singing or moping in their cages.”

far above their beds, jammed the broken trees against the bridges until they formed high timber dams, and, pushed harder than ever by the dams, rose and rushed along the streets of sleeping villages on the valley side, peeling off the front of houses like wet cardboard, and killing more than 100 people in a few minutes. Half a mile of that little valley smelled of death. There were corpses in the mud and in one house the table in an upper back room had been late for breakfast. In several other houses canaries were singing or moping in their cages.”

After his major scoop the Times offered Cockburn a quicker path to his goal, skipping two lower rungs of the career ladder and moving directly to an editorial job in the Foreign Room, readying correspondents’ dispatches for print. He declined again. Then he realized that he had already received and spent the last installment of his fellowship payment, so he accepted the position, moved to London, and yearned for reassignment.

One day, irked by a story by a journalist named Pugge that glorified the forces of law-and-order in Berlin, Cockburn drafted and put on Pugge’s desk “the dispatch which I conceived Pugge would have written — From Our Own Correspondent in Jerusalem — had he been covering events there approximately 2,000 years ago. It was a level-headed estimate studded with well-tried Times phrases. ‘Small disposition here,’ cabled this correspondent, ‘quote attached undue importance protest raised certain quarters result recent arrest and trial leading revolutionary agitator followed by what is known locally as ‘the Calvary incident.’ The dispatch was obviously based on an off-the-record interview with Pontius Pilate. It took the view that, so far from acting harshly, the government had behaved with what in some quarters was criticized as undo clemency.’ It pointed out that firm government action had definitely eliminated the small band of extremists, whose doctrines might otherwise have represented a serious threat for the future.”

Pugge glanced at Cockburn’s draft, saw the familiar cliches, and passed it on along with his report from Berlin. The prank was discovered, Pugge was outraged, but Cockburn’s career was not derailed. His Uncle Frank, a Canadian banker “who looked upon Europe as a little more than a fascinating museum in which it was good for people on holiday to pass a certain amount of time each year,” had a friend on the Times board of directors. The friend saw to it that Cockburn would get assigned to New York if he he was approved by the current Wall Street correspondent, Louis Hinrichs. After a trip by Hinrichs to London in 1929, he got the go-ahead.

Becoming a Communist

In 1927, surveying the crowd at a party given by a Viennese Baroness, Claud Cockburn had had a realization.

They were for the most part Austrians, Hungarians, Poles or Russians… Most of them were between the ages of 25 and 45… All of them been inescapably involved in the social upheavals and conflicts of the years after 1916… what all of them despite their curious differences of view, shared… was a recognition of Communism as the central dominating factor of our century. A platitude of course. To people nowadays such a recognition may seem a somewhat limited achievement, but I am speaking of the year 1927…

I began to be irked by my own ignorance of the events and particularly of the writings which had so profoundly affected these peoples lives. Reluctantly, because I felt sure it would be tedious and utterly wrong-headed and mistaken, I bought in Vienna… a volume nicely printed now and freely displayed in the book shop containing all those pamphlets and manifestos of Lenin and Zinoviev which 11 years before had to be smuggled dangerously across Europe… I found them shocking, repugnant, alien. They pricked and tickled like a hair shirt. They seemed to generate an intolerable heat. They existed in the world of notions with which I had no contact, and, exasperatingly, they dared totally and contemptuously to disregard most of the assumptions which I have been brought up and educated, or else to treat them brusquely as dangerous delusions peddled by charlatans bent on deceiving the people.

By 1929, Cockburn writes, he “had read Das Kapital and the 18th Brumaire and The Civil War in France and other works of Marks and Lenin; State and Revolution, and Imperialism, and Materialism and Empirical Criticism, and been particularly impressed by Bukharin’s Historical Materialism. Yet at the same time highly informed books continue to appear in quantity, proving that what was happening in the United States in that year of boom, 1929, was making the surest nonsense of Marx, Lenin, Bukharin and everyone else of their way of thinking. The United States hung over my thoughts like an enormous question mark. I felt that I should never be able to make up my mind about anything unless I went there and saw for myself.”

As the stock market was rising to ever-higher heights in the summer of 1929, Claud Cockburn got assigned by The Times to its New York office. (Whereas The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and other Timeses must identify their city of origin, the august daily published in London is simply The Times.) Cockburn was then 25 and very keen to understand the United States. He had spent two years reading Marx and Lenin, whose analyses of capitalism jibed with what he was observing in Europe. But the prosperity of the US seemed to refute any notion that the rich-poor system was unsustainable.

“In New York you could talk about prohibition, or Hemingway, or air-conditioning, or music, or horses,” Cockburn writes in his hard-to-find autobiography, I, Claud… “but in the end you had to talk about the stock market, and that was where the conversation became serious… The atmosphere of the great boom was savagely exciting, but there were times when a person with my kind of European background felt alarmingly lonely. He would’ve liked to believe, as these people believe, in the eternal upswing of the big bull market, or else to meet just one person with whom he might discuss some general doubts without being regarded as an imbecile or a person of deliberately evil intent —some kind of anarchist, perhaps.”

Cockburn didn’t reveal his doubts about the endless boom to Paul Hinrichs, The Times correspondent in New York, until one day Hinrich expressed doubts of his own. At that point, Cockburn writes, “I was as astonished as a member of some underground movement in an occupied country who discovers that the local captain of police is of the same opinion as himself. Excited by the extraordinary disclosure of Hinrich’s skepticism, I drew exaggerated conclusions. ‘Then you mean,’ I said, ‘that you believe that the capitalist system won’t work?’

“But this was not what he meant at all. He meant simply that the capitalist system —a phrase he somewhat disliked, I think, because it implies the existence of other, equally valid, systems— would proceed as usual by a series of jerks frequently interrupted by catastrophes. To ‘defend,’ so to speak, the catastrophes seemed to him unnecessary, for he considered them as inevitable as sunrise. There was not, in his view, a ‘system’ to blame; if one had to blame anything, then it was just life. The capitalist system was life, and therefore attempts to substitute any other type of ‘system’ were both nonsensical and dangerous. You could not step out of life.”

On the morning of October 24, 1929, Cockburn was in an office adjoining The Times’s. “There were some very smart people hanging over the ticker at the opening of the market that morning in the Sun office,” he recounts, “but none of them was quite smart enough to know that, as they saw in those first two astounding minutes, shares of Kennecot and General Motors thrown on the market in blocks of five, ten, and fifteen thousand, they were looking at the beginning of a road which was going to lead to the British collapse of 1931, to the collapse of Austria, to the collapse of Germany, and at the end of it there was going to be a situation with Adolf Hitler in the middle of it, a situation… Which was going to look very much like the fulfillment of the most lurid predictions of Marx and Lenin.”

Soon, Cockburn goes on, America would be engulfed by “a crisis which no one would admit he existed, so that… Unemployed men in Chicago had to fight one another for first grade at the garbage can put out at the back doors of the great hotels because a full and proper system of unemployment relief would have been socialistic, and above all would’ve been an admission of the existence of a crisis of scarcely believable proportions.” Washington, DC, was replacing Wall Street as the main source of US news, and Cockburn was assigned to start 1930 at The Times’s Washington office.

His arrival was propitious. He writes that he was “glad to get away from the atmosphere of New York at this period, and to get also to the political center of affairs… Sliding into Union Station, Washington, in the darkness of New Year’s Eve, I reflected momentarily that the last member of my family to visit the American capital was Admiral Sir George Cockburn, who had burned the White House and the capital, and much else of Washington besides, in 1814… As I left Union Station there was a considerable glare in the sky. The dome of the Capitol had just burst into flames.”

He was to stay at the house of Wilmott Lewis, The Times’s Washington correspondent, whom he had yet to meet. Lewis, he writes,

was entranced by the occurrence at the Capitol. Holding both my hands in his he beamed upon me. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘One sees at once that you have been born under the right star. You have luck, and that is the most important thing in life….’

Before he had even finished speaking he lifted the receiver of the telephone in the hall and communicated the story, decorated with some remarkable grace notes of his own, to all the columnists in Washington, and to two in New York. In the brief intervals between the calls he gave me a little lecture on the values of publicity in facilitating one’s serious work, and smoothing the path towards one’s real objectives.

‘Do any of the people you have been talking to,’ I asked, ‘know what actually caused the fire tonight?’

‘They suppose,’ he said, ‘that it was a painter. The inside of the Dome is being re-decorated. One of the painters, no doubt drunk since it is New Year’s Eve, probably dropped a cigar among the paint and varnish. However, it is what one may call “The Cockburn Angle” that makes the story.’

Lewis then led Cockburn to another part of the house, where a New Year’s Eve party was going on and newcomer beheld, “About thirty of the best-informed people in Washington rattling the tall windows with their gossip, and the yells and incantations of two senators, congressman, several journalists, and the then Mrs. Lewis, daughter of the owner of the Associated Press, who were on their knees shooting craps in the middle of the carpet.”

Wilmott Lewis would be Cockburn’s third superb mentor. Among his memorable bits of advice Lucky Claud quotes: “Take the charitable view, bearing in mind that every government will do as much harm as it can and as much good as it must.” And, “Remember, old boy, whatever happens, you are right and London is wrong.”

After the sensational murder of the Chicago Tribune’s crime reporter (who moonlighted as liaison between Al Capone and the Police Department), Cockburn arranged to interview the famous gangster. Running rackets in Chicago, Capone told him, was his alternative to poverty in Brooklyn. Whatever Cockburn said o commiserate upset the gangster. “‘Listen,’ he said, ‘don’t get the idea I’m one of these goddamn radicals. Don’t get the idea I’m knocking the American system. The American system…’ As though an invisible chairman had called upon him for a few words, he broke into an oration upon the theme. He praised freedom, enterprise, and the pioneers. He spoke of ‘our heritage.’ He referred with contemptuous disgust to Socialism and Anarchism. My rackets, he repeated several times, are run on strictly American lines and they’re going to stay that way.”

When Cockburn wrote up the interview for the Times, he “doubted whether the paper would be best pleased to find itself seeing eye-to-eye with the most notorious gangster in Chicago.” But the higher-ups were pleased enough to give him a bonus.

“Nothing sets a person up more,” Cockburn writes in I, Claud…, “than having something turn out just the way it supposed to be, like falling into a Swiss snow drift and seeing a big dog come up with a little cask of brandy around its neck. The first time I traveled on the Orient Express I was accosted by a woman who was later arrested and turned out to be a quite well-known international spy. When I talked with Al Capone there was a submachine gun poking through the transom of the door behind him. Ernest Hemingway spoke out of the corner of his mouth. In an Irish castle a sow ran right across the baronial hall. The first minister of government I met told me a most horrible lie almost immediately.”

About the newspaper business Cockburn writes: “It seems to me that a newspaper is always a weapon in somebody’s hands, and I never could see why it should be shocking that the weapon should be used in what is the owner conceived to be his best interest. The hired journalist, I thought, ought to realize that he is partly in the entertainment business and partly in the advertising business —advertising either goods, or a cause, or a government. He just has to make up his mind who he wants to entertain, and what he wants to advertise. The humbug and hypocrisy of the Press begin only when newspapers claim to be impartial and ‘servants of the public.’ And this only becomes dangerous as well as laughable when the public is fool enough to believe it.”

Cockburn’s Weekly

By 1932 Cockburn was chafing at the bit, politically, and “secretly bootlegging quite a number of pieces of news and articles to various extreme Left American newspapers and news services.” He gave notice to The Times and in response was offered a raise and a couple of months’ paid leave. “Humiliated to find that my important decision had been interpreted in these quarters as an act of vulgar blackmail,” he declines their offer, intending “to walk out of The Times and onto a boat, tour Europe, and then see what was best to be done.” But as usual, he over-estimated his savings. He dashes off an anonymous “Inside Washington” book, gets paid, and sets sail.

“To come to Berlin just then, after New York,” Cockburn writes, “was to be whisked down suddenly from the gallery of a badly lit theater and pushed against the flaring footlights to see that what you thought you saw from back there is really going on. Already the storm troopers were slashing and smashing up and down the court first then down, and there were beatings and unequal battles in the city streets… I might have dithered about for weeks or even months had not something jogged my elbow. This time it was Hitler. He came to power. I was high on the Nazi blacklist. I fled to Vienna. There I sat down to consider seriously a notion which had been buzzing in my mind for some time…”

Cockburn’s notion would take the form of mimeographed weekly called The Week that was read by the political influencers of 1933. I, Claud includes a paean to “the humble mimeograph machine,” the poor journalist’s answer to “the mass-production newspaper, the telephone, the radio, and the talking picture.” Cockburn’s goal for The Week was not to reach the masses (he was not yet a Communist) but to reach readers who were “influential, either because of the position they hold, or the money they have, or because like newspapermen, they are sitting at the feeding end of a pipeline with millions of people at the other end of it.”

In the spring of ’33 Cockburn returned to England and set about launching the publication he had in mind. He found himself “constantly frustrated by the habit people have got into of considering that nothing important can be done without going through the ritual of a conference —and for two pins they will set up a committee.”

He came to a realization: “I had not left The Times for the purpose of saddling myself with another editorial board and some more shareholders and advertisers. After 30 days of patient investigating I had grasped more firmly than ever the truth that what one must do was to ensure that the paper was all of a piece and all under one control. It should express one viewpoint and one viewpoint only: my own. In other words, size must be sacrificed to coherence and to unity of style. Plus after four weeks of bumbling more or less agreeably about London, I came to the conclusion that the thing to do was cut the cackle and start the paper regardless of what anybody might say, warn or advise.”

Cockburn borrowed a small sum from a gent he’d known at Oxford and made him a partner, though the man had “a positive horror of business” and “scarcely knew where to buy a stamp.” He rented an office and hired a secretary who was “the daughter of a backwoods baronet… pretty, energetic, intelligent and loyal, but she could not type.” A 1,200-name mailing list was purchased from “a temporarily defunct” London weekly called Foreign Affairs. Journalists in London as well as those Cockburn had known in Berlin, New York and Washington were invited to provide material.

Cockburn’s partner wanted The Week to have a “clean and dignified” look, but he wanted it to be “noticeable.” He prevailed. The final product was mimeographed in dark brown ink on buff-colored foolscap [close to our “legal-sized” paper]. It was not only noticeable, it was unquestionably the nastiest looking bit of work that ever dropped onto a breakfast table…. To deepen the confidential atmosphere, I preferred, although it cost three times as much to do so, to mail the paper to subscribers in closed envelopes.”

The first issue went out to the 1,200 purchased names and Cockburn pictured about 800 of them “sitting down to send off their twelve-shilling postal orders for the Annual Subscription.” But only seven subs were sold from that initial mailing.. “No one had warned me,” Cockburn writes in I, Claud…, ” that the Foreign Affairs list was years old… The news spread rapidly among friends and acquaintances that my big idea had misfired… Things remained extremely difficult for several weeks, until one day, with the circulation awfully steady at 36, the Prime Minister intervened.”

The Week had devoted a special issue to “what was really being said by informed observers” at the World Economic Conference, which Prime Minister Ramsey Macdonald was hosting in London. Cockburn’s sources said the conference was accomplishing nothing, a waste of time and money. Macdonald called an off-the-record press conference to denounce the critics. The scene as described by Cockburn: “Everyone pushed and stared, and what he had in his hand was that issue of The Week; and he went on to quote from it, and to warn one and all to pay no heed to the false prophets of disaster, activated by motives of this, or that or the other thing. This was good strong stuff, and stimulating to these people who hitherto had never heard of The Week, and, but for this, possibly never would have.” He raced back to the office to answer the phone, which he knew would be ringing off the hook.

Within two years, Cockburn writes, “This small monstrosity, The Week, was one of the half dozen British publications most often quoted in the press of the entire world. It included among its subscribers the foreign ministers of 11 nations, all the embassies and legations in London, all diplomatic correspondents of the principal newspapers in three continents, the foreign correspondents of all the leading newspapers stationed in London, the leading banking and brokerage houses in London, Paris, Amsterdam, and New York, a dozen members of the United States Senate, 20 or 30 members of the House of Representatives, about 50 members of the House of Commons and 100 or so in the House of the Lords, King Edward VIII, the secretaries of the leading trades unions, Charlie Chaplin and the Nizam of Hyderabad.

“Blum read it and Goebbels read it, and a mysterious warlord in China read it. Senator Borah quoted it repeatedly in the American Senate and Herr von Ribbentrop, Hitler’s Ambassador in London, on two separate occasions demanded its suppression on the ground that it was the source of all anti-Nazi evil.”

Next installment: From The Week to the Worker….