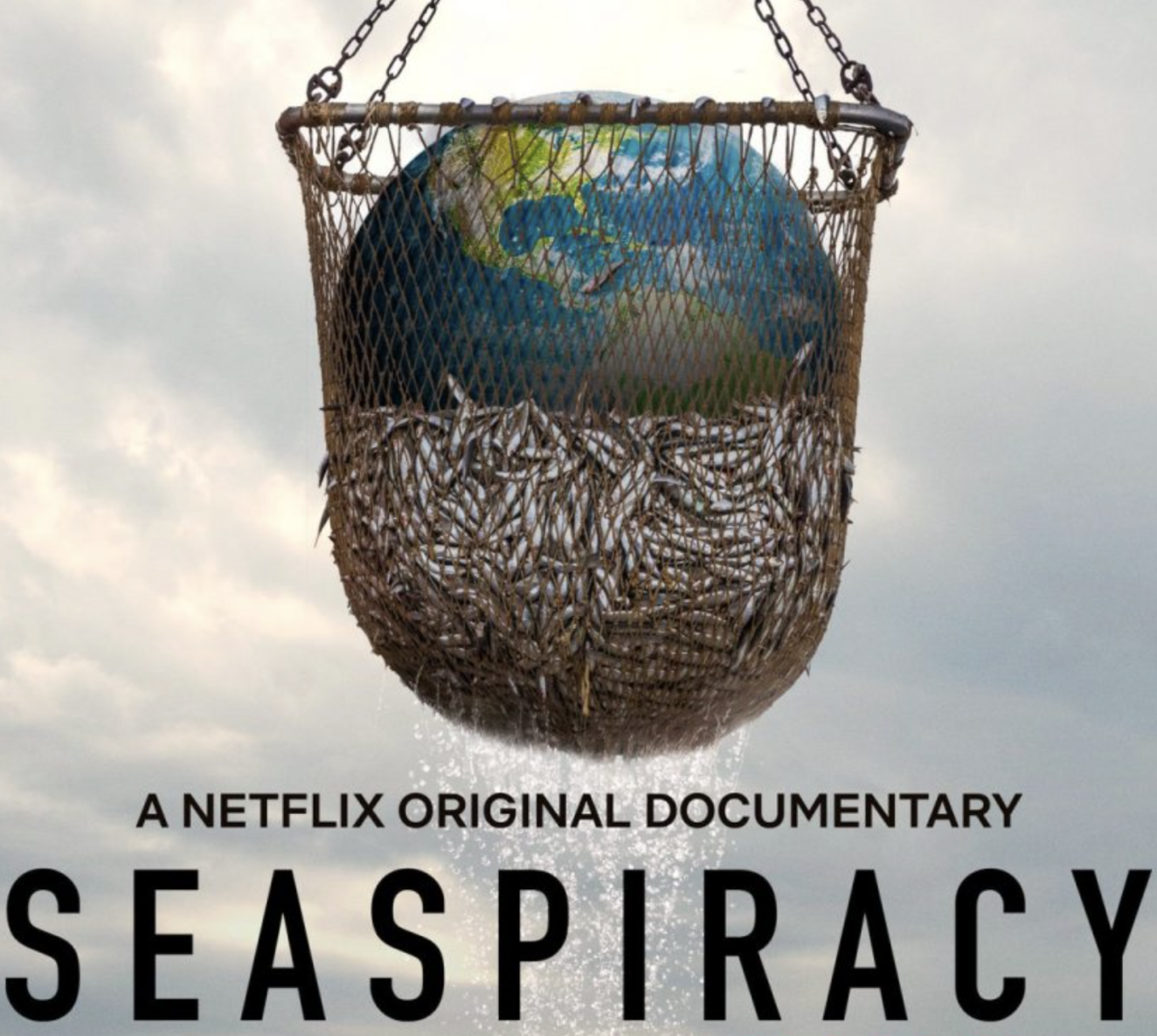

Don’t let the title of this review fool you. The new (awfully named) polemical documentary Seaspiracy, now streaming on Netflix, gets a lot right, but its shortcomings undermine its potential positive influence.

Following the journey of 27-year-old director Ali Tabrizi as he explores what the hell is going on with our oceans, we are informed, for instance, that while plastic nanoparticles are destructive and illegal whaling and Japanese dolphin hunts are bad, it’s commercial fishing that is the real threat to the world’s oceans. Tabrizi is not entirely wrong in his assessment. When the apex predators like sharks disappear, the oceans will eventually die off and take humans along with them. Yet the answer as to how we deal with the destruction caused by fisheries, and other contributing factors that are not examined, is where the documentary drowns in its own polluted waters.

This isn’t to say Seapiracy is a total waste. At times it’s a damning exposé of the vicious inner-workings of the international fishing cabal. Visceral scenes onboard commercial fishing vessels, the de-fining of sharks, and bloody, dead whales. It’s packed full of jarring stuff, sure to shake anyone who has never thumbed through a PETA pamphlet.

In addition to its gruesome scenes, Tabrizi also pokes holes in the Marine Stewardship Council sustainable labeling that grace the cans of tuna and other seafood in our markets (years ago I investigated a similar problem when it came to the USDA’s organic seal of approval). He also goes after the Earth Island Institute’s dolphin initiative, using the clumsy words of associate program director Mark Palmer, against him. Palmer rightly points out that nothing can be considered “100%” dolphin safe, but Tabrizi quickly turns this into a grand conspiracy, which he claims is meant to swindle consumers and enrich global fisheries. While this is an obvious stretch, the film is correct that labeling practices can certainly be abused, and there is a particular profit motive for the companies to include such information on their products, giving buyers the false sense that their tuna sandwiches are absolutely not being served with a side of dolphin. Nonetheless, claiming there is some sort of ill-intent on the part of Earth Island is problematic at best, and libelous at worst.

“The dolphin-safe tuna program is responsible for the largest decline in dolphin deaths by tuna fishing vessels in history,” responded David Phillips, director of Earth Island Institute and the International Marine Mammal Project, following the film’s release. “Dolphin-kill levels have been reduced by more than 95 percent, preventing the indiscriminate slaughter of more than 100,000 dolphins every year.”

Tabrizi proceeds to interview a spokesperson for the Plastic Pollution Coalition, a project of the Earth Island Institute. Its executive director, Dianna Cohen, appears to be caught off-guard and allegedly refuses to condemn personal fish consumption. This was clearly an edited “gotcha” moment. This instance and the entire organization, which has a connection to Earth Island Institute, is proof, according to Tabrizi, that they must have an ulterior motive. They don’t. They just focus on plastic pollution.

For five years I worked for CoalSwarm (now Global Energy Monitor) a former project for Earth Island Institute, and I can assure you that Earth Island does not intrude on its project’s inner-workings. They essentially provide non-profit cover for many small organizations, handling the paperwork so activists can focus on their work. There’s no conspiracy here. In the end, however, these are just minor squabbles, the larger failure of Seapiracy is that its almost singular answer to remedying the ocean’s ills is to make the personal decision to stop eating fish.

If only it were that straightforward. For starters, the majority of fish consumed globally does not happen in the United States or the UK where Tabrizi is based. The Chinese, by far, eat the most sea animals, over 65 million tonnes per year, Japan consumes 7.4 million tonnes, Indonesia 7.3 million tonnes, with the U.S. trailing behind at 7.1 million. While this is still a lot of sea creatures, even if everyone in the United States stopped eating fish, the growing population in China, along with the country’s fish consumption, would continue to be a huge mess for our world’s oceans.

This brings us to another problem that’s not discussed in Tabrizi’s film: population growth and its connection to the destruction of oceanic life. Not surprisingly, as the human population exploded over the past 100 years, industrialized fishing increased right along with it. In many communities around the world, fish still provide essential nutrients. In the U.S. and Europe, eating fish may be a luxury, but for many of the world’s impoverished nations, fish are a necessity. Tabrizi does not even attempt to face this fact, perhaps because it’s overly complex, or perhaps because it creeps into neo-Malthusianism territory, which has haunted the environmental movement for decades. Either way, any important analysis of the over-fishing of our world’s oceans, as uncomfortable as it may be, must broach the topic.

Then there’s the issue of capitalism. Commercial fisheries are profitable enterprises, estimated to surpass $438 billion by 2026. While the film briefly addresses slave labor on fishing vessels in places like Thailand, it does a poor job of handling the ways in which globalization has exacerbated the matter and will continue to do so as long as the world’s marketplace expands.

Although these are glaring oversights, the largest omission of the film is its brushing over fossil fuel’s central role in oceanic destruction. Even if all commercial fishing were to halt but fossil fuels continued to burn unmitigated, the future of our oceans would remain in peril. There are many impacts, from unforeseen fish migration to acidification. Corral reefs, for example, are experiencing the brunt of our warming planet’s toll on the ocean. From bleaching to harboring infectious diseases as waters heat up, these delicate ecosystems are being destroyed by climate change at a terrifying rate. Over-fishing is a contributing factor, but it’s our fossil fuel addiction that is largely to blame. Even healthy oceans can only absorb so much CO2. Eventually, these carbon sinks will fill up. As they do, ocean waters will continue to warm, altering their various ecosystems, creating new weather patterns and underwater circulation. Predators will struggle to survive and the oceans will eventually die off.

Each of these topics — global population, capitalism and climate change, while intricately linked — deserve further exploration. Even so, despite my various gripes with Seaspiracy, the film will be a captivating eye-opener for many, not only to fishing’s various cruelties but also as to why conservation orgs like Sea Shepherd, who are risking everything on the front lines, ought to be supported.

Ten years ago, Jeffrey St. Clair and I met up with Captain Paul Watson, founder of Sea Shepherd, in Seattle for some beers and (vegan) Chinese food. After a couple of rounds, Watson became adamant that we ought to focus global conservation efforts on two big ticket items: defending sea predators as they balance and control the health of our seas, and designating massive swaths of the ocean as sanctuaries, free from fishing operations and fossil fuel extraction. These huge protected regions, Watson argued, are just as vital as preserving rainforests in fending off the wrath of climate change. Perhaps even more so. As Seaspiracy points out, currently 6.3% of our oceans are qualified as Marine Protected Areas, but a mere 1.8% don’t allow any fishing. If we are to get serious, this must change fast. Yet questions remain. How do we do this without starving much of the world? How will such an effort be managed equitably? These are tough questions that are never probed in Tabrizi’s film.

Sure, don’t trust the labels. Stop eating fish, especially those caught commercially. This might be a good start, but unlike the answer provided in Seapiracy, it’s only a single piece of a much larger, more complicated puzzle of planetary survival, not just for precious sea life, but for humans as well.