Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

Part 1 of a 4-part Primer on Disaster Collectivism in the Climate and Pandemic Crises

Climate change and pandemics are sad and frightening topics, but they can also be viewed as an unprecedented opportunity for 21st-century societies. These crises can become an excuse to quickly make necessary changes for a healthier future for people and the planet that otherwise may take many years to implement. Times of disaster, whether or not they are triggered by climate or health catastrophes, are opportunities to focus on the need for social and environmental change, and our response to disasters may contain the kernels of a better world.

One cartoon depicting a climate change summit sums up the irony. The conference agenda displays the desperately needed measures to lessen greenhouse gas emissions: “Preserve rainforests, Sustainability, Green jobs, Livable cities, Renewables, Clean water, air, Healthy children.” A perturbed white man turns to a Black woman and asks, “What if it’s a big hoax and we create a better world for nothing?”

The cartoon could just as easily depict a COVID-19 summit, which advocates instituting universal health care and unemployment relief, suspending evictions and deportations, building the public sector, and promoting mutual aid among neighbors.

Joel Pett, Planning.org.au.

Public attitudes to climate change are often shaped by direct experience of climate instability and disaster. Climate change is accelerating disasters such as wildfires, floods, heat waves, droughts, storms, and landslides, depending on where one lives. But a wide range of other natural and human-made disasters also shape human society and consciousness, including pandemics, earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic activity, wars, mass violence, and radioactive and toxic leaks.

We studied all these threats in the class “Catastrophe: Community Resilience in the Face of Disaster,” which I have twice co-taught at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. How we prepare for and respond to these emergencies speaks volumes about the values and priorities of our society.

Resilience can be defined as “the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness….the ability of a substance or object to spring back into shape; elasticity.”

Indigenous cultures, which have persevered through the overwhelming odds of settler colonialism, environment destruction, epidemics, violence, and forced assimilation, embody the concept of resilience.

In the Pacific Northwest, the annual Tribal Canoe Journey brings more than one hundred canoes from dozens of Native nations to converge at a host nation, to share songs and dances and involve youth deeply in cultural revitalization. In the Great Lakes region, Ojibwe elder artist and author Rene Meshake (as quoted by Turtle Island Institute co-director Melanie Goodchild) beautifully described resilience using the Anishinaabemowin term sibiskaagad, “a river flowing flexibly through the land.”

Resilience can be applied to different scales: the resilience of individuals (to heal from physical and psychological harm, and live a healthier life), the resilience of communities (to recover from historical trauma by revitalizing cultures and rolling back inequalities through social justice), and resilience of the planet (to reverse environmental and climate crises, and regenerate life). All three of these scales of resilience are bound up in the study of disaster preparedness, response, and recovery.

Studying Disaster Resilience

Between 1995 and 2015, more than 600,000 people around the world died from disasters and 4.1 billion people were injured. Academic studies have most often focused on government or NGO responses to catastrophes, and only recently focused on themes of grassroots community resilience in the face of disaster.

As Douglas Paton observed in his Disaster Resilience: An Integrated Approach, “Humankind has a long history of confronting and adapting to the devastation caused by war, pestilence, disaster and other catastrophic events. That such experiences can have beneficial consequences has, however, often been overlooked by research that has focused primarily on physical losses and the anguish of survivors in the immediate aftermath of disaster. However, when the time frame within which analyses are conducted and the range of outcomes assessed is extended, evidence for positive outcomes has been readily forthcoming.” Paton viewed community preparedness for a range of hazards as critical to the outcome of any possible disaster scenario.

Research studies generally agree that disaster preparedness “is not effective without the participation of vulnerable communities.” Key factors in community resilience are “citizen involvement in mitigation efforts, effective organizational linkages, ongoing psychosocial support, and strong civic leadership in the face of rapidly changing circumstances,” and “the ability of community members to take meaningful, deliberate, collective action to remedy the impact of a problem, including the ability to interpret the environment, intervene, and move on.”

One case study in North Dakota, for example examined preparations for the 2009 Fargo floods, in which residents had five days to lay sandbags along the Red River of the North, and successfully mitigated most harmful effects of the spring flooding. It concluded that resilient communities rely “upon pre-existing adaptive capacities (e.g., economic development, social capital, information and communication, and community competence) that can be mobilized during a disaster.” The Red River Resilience project educated residents to “foster hope, act with purpose, connect with others, take care of yourself, search for meaning.”

Another research study documented that “disasters attributed to an act of nature evoked a sense of shared fate that fostered cooperation,” but that “community civic capacity” is key to the success of that cooperation. It cited the example of a 1995 Chicago heat wave that caused fewer deaths in a Latin American immigrant community than in a neighboring U.S.-born communities, due to the interlocking family and neighborhood organization connections that caused community members to check on the elderly.

In crisis situations, a “brotherhood of pain,” or “a form of spontaneous social solidarity emerges that temporarily enables people to put aside self-interest and come together in common effort. And equally recurrent, this solidarity proves fragile and gives way to intense expressions of self-interest.” Contrasting the experiences of Salvadoran refugees in two earthquake relief camps suggested that “elements of dignity, participation and respect for the capacity of the victims to control their own lives are relevant factors for effective individual and community coping after a catastrophe.”

The phenomenon of “adversarial growth,” drives “positive change following trauma and adversity.” The social-psychological process of reorientation affects individuals and communities navigating “the psychological, social and emotional responses to the symbolic and material changes to social and geographic place” that result from disaster.

Human geographers have studied “ways of relating” in engaging in generosity and hospitality toward others, and explored the “geographies of generosity,” particularly at a distance. The geographies of caring and hospitality are closely bound up with “geographies of responsibility,” including the relationship between identity and responsibility and the potential geographies of both.

Hazard geography researchers have sought to build place-based models for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Within the U.S., “the “Midwest and Great Plains states have the most inherent resilience, while counties in the west, along the US-Mexico border, and along the Appalachian ridge in the east contain the least resilience.” Yet the most important resilience differential is not between regions or communities, but within communities.

Not surprisingly, “social groups within a community differ insofar as their levels of resilience and the threats to which they are resilient.” The factors of race, education, and age most consistently moderate “the impact of disaster exposure on receipt of postdisaster support,” and disasters tend to exacerbate existing social, gender, and economic inequalities.

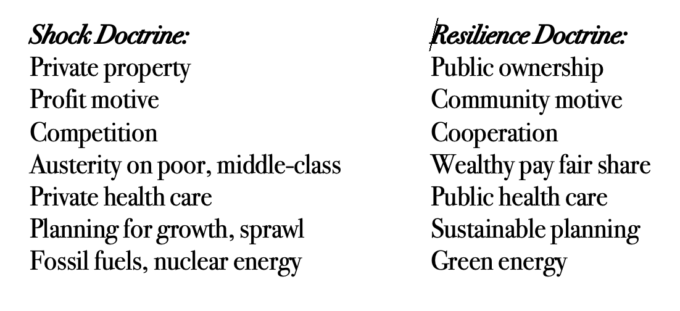

Shock Doctrine vs. People’s Renewal

Disasters are often used to centralize political and economic control, and thereby deepen human inequalities, as Naomi Klein described in her classic 2007 study The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. She documented how after the “shock” of natural or human-made disasters, corporate interests move in to privatize the economy, institute the “shock” of austerity, and repress and “shock” (torture) citizens who resist. These neoliberal capitalist interests take advantage of a major disaster to push austerity policies that a distracted and desperate population would be less likely to accept under “normal” circumstances.

Klein used Hurricane Katrina’s devastation of New Orleans to explain how disasters provide windows into a cruel “and ruthlessly divided future in which money and race buy survival.” She predicted that with “resource scarcity and climate change providing a steadily increasing flow of new disasters, responding to emergencies is simply too hot an emerging market to be left to the nonprofits.”

Less noticed in Klein’s study was her assertion that the Shock Doctrine had a flip side, which she termed the “People’s Renewal,” represented by the Common Ground Relief community-based response to Katrina. She observed that “the best way to recover from helplessness turns out to be helping—having the right to be part of a communal recovery…. Such people’s reconstruction efforts represent the antithesis of the disaster capitalism complex’s ethos…. These are movements that do not seek to start from scratch but rather from scrap, from the rubble that is all around.”

Klein concluded, “Rooted in the communities where they live, these men and women see themselves as mere repair people…fixing it…making it better and more equal. Most of all, they are building in resilience – for when the next shock hits” (589). She therefore tied the responses to climate change-induced disasters to how communities can increase awareness of sustainable methods to prevent future disasters, share resources among neighbors, and deepen lasting cooperation.

In her 2014 book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, Klein analyzed a typhoon that devastated the Philippines and floods that ravaged Europe, noting that “during good times, it’s easy to deride ‘big government’ and talk about the inevitability of cutbacks. But during disasters, most everyone loses their free market religion and wants to know that their government has their backs” (107).

Subsequent catastrophic storms, such as those that struck Texas, Puerto Rico, and Bangladesh in 2017, have reinforced how disasters can exacerbate economic and racial inequalities. Klein’s 2018 book The Battle for Paradise, showed how Puerto Rican community organizations have been trying to rebuild from the devastating Hurricane Maria by emphasizing renewable energies, agro-ecological farming, and decentralized, democratic management. These projects were coordinated by a network of Centros de Apoyo Mutual (mutual aid centers), or community hubs with “ the ultimate goal to restore power — both electric and civic — to the people.”

Centros de apoyo mutuo / Mutual Aid Centers (facebook).

Klein applied the same “shock doctrine” formula to “coronavirus capitalism” in the 2020 pandemic. She asserted “Look, we know this script…. a pandemic shock doctrine featuring all the most dangerous ideas lying around, from privatizing Social Security to locking down borders to caging even more migrants…But the end of this story hasn’t been written yet. Instead of rescuing the dirty industries of the last century, we should be boosting the clean ones that will lead us into safety in the coming century. If there is one thing history teaches us, it’s that moments of shock are profoundly volatile. We either lose a whole lot of ground, get fleeced by elites, and pay the price for decades, or we win progressive victories that seemed impossible just a few weeks earlier. This is no time to lose our nerve.”

The Resilience Doctrine

This concept could be called “Disaster Collectivism” or “Disaster Cooperativism”—the opposite of “Disaster Capitalism.” As a corollary to the “Shock Doctrine,” I would propose the “Resilience Doctrine.” Communities can prepare for and respond to a major emergency with cooperative ways to ensure immediate survival, and to engage people in exploring social and environmental solutions that they would be less likely to accept under “normal” apathetic circumstances.

In contrast to the Shock Doctrine, the Resilience Doctrine emphasizes public ownership over private property, the community motive over the profit motive, cooperation over competition, economic equality over austerity, sustainable planning over growth planning, public over private health care, planning for sustainability rather than only growth, and green energy over fossil and nuclear fuels.

The Resilience Doctrine strengthens the ability of local communities and cultures to sustain shocks, draws on precedents of “disaster collectivism” to rebuild communities across racial and cultural barriers, and promote greater social and ecological equality. Since disasters bring out the best in people, as well as the worst, they should be studied to lessen harm to the human and natural world, and to provide a little inspiration and hope.

Signs of hope are emerging from disaster-affected communities, regardless of their ideology, in cooperative relief projects and mutual aid networks based on “solidarity, not charity.” Mutual aid promotes the voluntary exchange of resources and services, respecting and learning from each other through horizontal, reciprocal interaction, rather than merely helping or assisting in top-down, vertical interaction. The mutual aid model has multiple historical roots, in socialist and anarchist movements, churches, labor unions, African American and immigrant community networks, neighborhood groups, and Indigenous nations. Some of these practices are rooted in ancient traditions, drawing from the past to build a present that prefigures a healthier future society of resilience and regeneration. As discussed later, mutual aid networks have vastly expanded in the context of hurricanes, wildfires, floods, and other climate change-fueled disasters, as well as during the coronavirus pandemic.

The concept of resilience has been commonly misinterpreted under neoliberalism, with its stress on how the individual, and not society, are responsible for their own lot in life. When faced with adversity, this version of resilience advocates, an individual should simply persevere, increase their own personal capacities, or “buck it up” to get through and survive. As the Flint doctor Mona Hanna-Attisha asserted, “Surviving life’s hardest blows should not be celebrated — or expected. Recovery and reconciliation require reparations and resources. To expect resilience without justice is simply to indifferently accept the status quo.” Resilience is not just about survival, because the capacity of human beings to withstand stress and recover from difficulties is only possible through transforming current social structures and our relationships with the natural world, and moving toward a thriving society of justice and regeneration.

“The Response” Shareable podcast (from KaneLynch.com).

Puerto Rican mutual aid organizer Astrid Cruz Negrón asserted, “The Mutual Aid Center definitely does not want to stay in the emergency mindset of surviving Maria. We want everything we do to build towards a new world, a new more just, more equal society.” According to Robert Raymond, of the Sharable Network, “climate resilience for the most vulnerable communities is often a byproduct of past efforts to organize and activate around a wide variety of causes that go beyond disaster relief. It is through the intersection of many ongoing struggles — from the realm of economics to that of race, immigration status, and so on — that communities can begin to not just build resilience to the storms, fires and droughts that await them, but to also ensure that they gain the political power to demand — and receive — the resources and aid that their governments owe them.”

The Resilience Doctrine:

A Primer on Disaster Collectivism in the Climate and Pandemic Crises

Part 1: An Introduction to Disaster Resilience

Part 2: How Disasters Can Encourage Social Change

Part 3: Indigenous Nations Understand Disaster Resilience

Part 4: Mutual Aid in the Pandemic and Beyond