L to R: Bayard Catron, Terry Bisson, Michael Horwatt, Mike Montrose, Bennett Bean, Phillip Brown, Peter Cohon (Coyote), James Smith,, Celia Chorosh (Segar), Jack Chapman, Mary Mitchell, Mary Lou Beaman, Ruth Gruenewald (Skoglund), Larry Smucker. Courtesy. Grinnell College, Scarlet and Black.

It was autumn in Iowa, it was 1961.

It was fifty years ago.

The sanitized 1950s, its Men in Grey Flannel Suits, and the Military-Industrial complex President Eisenhower warned about, were the dominant voices. Bob Dylan had just released his first record, and the folk music movement was emerging, but the old order maintained cultural hegemony.

Nuclear Armageddon was in the air. “On the Beach” was at the movies. Plans were afoot to install a bomb shelter in the basement of the Grinnell college library. The Russians were setting off nukes like boys with cherry bombs, and the US was about to resume atmospheric testing as well. According to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists’ “Doomsday Clock,” it was seven minutes till midnight. Like America, Grinnell College was on the cusp of change. The consciousness of a new generation was simmering and a few visionary students were seeking sanity in a world apparently bent on nuclear High Noon. Their initial ideas ranged from Letters to the Editor, to chaining themselves to the White House fence and fasting in protest, to packing for Australia.

Their intensity, intelligence and commitment, at a time when nuclear madness passed for normality, drew others to them. Passionate, focused discussions ensued and refined a strategy. President Kennedy’s proposed test-ban treaty provided the focus for a plan that was both judicious and bold.

Fourteen Grinnell students, four women and ten men, decided to drive the thousand miles to Washington, DC, and fast for three days in front of the White House. Others would stay behind to organize campus support. The common goal was to protest the nuclear arms race and the resumption of atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, support President Kennedy’s proposed test ban treaty and “Peace Race”, and force the subject into the public forum.

Professors were supportive and promised to let us make up work we would miss. Grinnell College President Howard Bowen granted us leave (but would not take a position politically). The Student Senate, at first resistant to our “representing the college,” was swayed by our resolve and finally voted their approval.

As one might expect, there was grassroots opposition as well. Soliciting support outside the Quad dining room, we collected clever quips such as “Go back to Russia” and “Better Dead than Red,” but a residence hall poll showed “65 percent in favor, and 35 percent opposed.” This was Grinnell, after all, which had welcomed abolitionist John Brown on his way from Kansas to Harper’s Ferry.

We issued a statement of purpose, which read in part:

We are not advocating new loyalties, we are urging the utilization of new means. We are not abdicating our responsibilities as citizens of the free world, we are saying that we want to inherit a world in which conflicts can be resolved rationally. In the present situation the probability of war is ever-increasing. If this is viewed objectively in the light of modern weapons technology, it is easy to see that in the event of a war, neither side can “win”. In effect, we are saying that war is an obsolete instrument for obtaining policy objectives, and that we as a nation must utilize new alternatives for setting disputes.

That was bold talk fifty years ago. Students were expected to train for a job, shut up and study, or drink till they puked. Foreign policy was for men of means. The reigning Midwestern liberal, Hubert Humphrey, called us together and tried to dissuade us on the grounds that our protest would only aid the enemy.

We had a clearer idea of what the real Enemy was, though, and would not be moved.

Control of our message was important. We did not want it co-opted or dismissed by a derisive press. The group agreed on a dress code: coats and ties for the guys, sensible skirts and stockings for the women. Clean cut would be the order of the day. We would represent a voice of sanity, respectable but firm.

One of the original visionaries, whose father had been red-baited out of government, offered to drop out so we wouldn’t be ‘tainted’ by the link. Instead we made him our leader and spokesman.

He and several members met with Grinnell’s Public Relations Office and pitched the proposition that our trip might be more successful (and reflect better on the college) if that office ran media interference and helped us “frame” the event and the issues before the press did.

The college contacted the Des Moines Register on our behalf. An article appeared, and other news outlets began to preview our trip. The late Peter Hackes, a well-known and respected broadcast journalist, and a Grinnell graduate, interviewed our leaders on the NBC radio program, Monitor. Wire services picked up the story, and attracted help from unlikely sources.

Hats were passed and two old cars were bought, a ’50 Ford six and a ’48 Chevrolet. A progressive insurance executive from Des Moines, read about us and lent us a brand new Chevrolet Impala company car and precious two-way radios for the trip.

Road maps (free in those days) were unfolded and we pulled out of campus onto Route 6 on November 13, heading east. There was no Interstate 80 those days, and we threaded two-lane roads until Chicago, and executed unnerving pas-de-deuxs with 18-wheelers on the Pennsylvania Turnpike, trying to keep each other in sight. Complex headlight signals, like semaphores, kept our caravan intact. We slept on one another’s laps and shoulders like puppies in a box. Gasoline was 30.9 a gallon, Cokes and Clark Bars a dime.

Base camp in Washington was Gaunt House, a shabby hostel near DuPont Circle, favored by impecunious job seekers and political protestors. The Speaker of the Senate, Sam Rayburn had just died and the town was deserted, but we held a press conference anyway. To our surprise, both AP and UPI showed up. The doughty little reporter from UPI was Helen Thomas, subsequently the doyenne of the White House press corps, a woman who made a career of speaking truth to power. Perhaps that’s why she liked us.

Suddenly, The Grinnell 14 were national news.

L to R: Ruth Gruenewald, Larry Smucker, “Jack” Chapman, Curt Lamb, Peter Cohon.

The first day without breakfast, marching in a circle on the sidewalk at 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., dressed as if for job interviews, was tough stuff, but fasting gets easier for the first three days.

President Kennedy was away, giving a speech in Arizona, but he read the papers. He sent a bright young staffer, Marcus Raskin, who sat with us on the threadbare rug at Gaunt House, soulful and sympathetic, and extended his boss’s invitation into the White House. JFK had set up a meeting with his National Security Advisor, McGeorge Bundy.

The next morning, we found ourselves seated across a table in the Fish Room, facing Bundy’s cold eyes totally devoid of empathy as he offered us orange juice and advice on how to conduct ourselves as citizens. We demurred on the orange juice. Not accustomed to being refused, Mr. Bundy reminded us that even Ghandi drank juice while fasting.

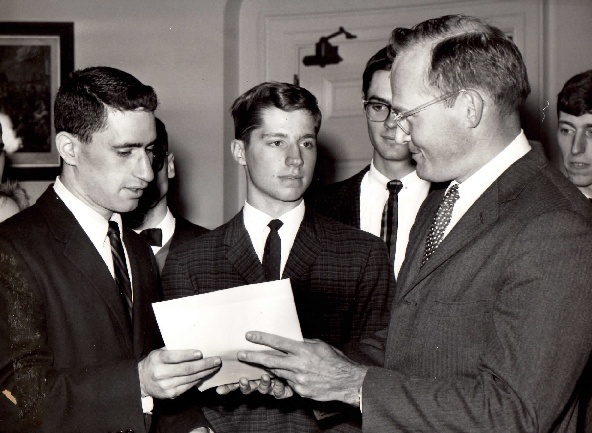

Mike Horwatt, Mike Montross, Curt Lamb, McGeorge Bundy, Bennett Bean. The original API caption read: Michael Horwatt, left, of Falls Church VA and fellow students at Grinnell College in Iowa deliver a message for President Kennedy to McGeorge Bundy, presidential adviser, at the White House, Nov. 17. The students are in Washington on a three-day “peace vigil”.

We stuck with water and presented our case. McGeorge Bundy remained immobile, a statue with slicked back hair, clear-framed glasses, dark, elegant suit, and gleaming white shirt and tie. Before long we left his chill for the friendlier cold outside.

Our White House invitation was news, and right-wingers (including American Nazi Lincoln Rockwell, in uniform!) were waiting to jeer and heckle. They gnawed on KFC drumsticks as we marched and fasted.

The next day, demonstrating even-handedness, we presented a petition to the Soviet Ambassador. Pravda and the Post showed up and snapped a photo of our spokesman shaking hands with the Russian Ambassador.

L-R: Peter Cohon,(Coyote), James Smith, Terry Bisson, Mike Horwatt, Mike Montross, Celia Chorosh (Segar), Bennett Bean, Russian Attaché Gennadi Paitakov, Naida Tushnet, Curt Lamb, Mary Mitchell,, Ruth Gruenewald (Skoglund).

We were international news.

Back on campus, our supporters had established office space and a phone in the offices of the Scarlet and Black, the campus newspaper. When the publicity broke, according to them, “all hell broke loose.” College students from around the country called to ask how they could join in. We had touched a chord. Soon our campus “Ground Control” was coordinating requests from other campuses, trying to schedule a continuous student protest presence at the White House. It was, they remember, “a heady first taste of organizing power with the possibility of turning feelings of civic responsibility into meaningful acts of social conscience.”

We broke our fast at a member’s suburban DC home, where his mom rewarded us with delicious chicken soup and hamburgers. As we were leaving DC, Bluffton College rolled in, and we learned from them that several others were scheduled to follow. The protests continued for over a year.

Driving home, our caravan was pulled over by State Troopers in Ohio. Suspecting the worst, we were surprised when courteous officers transmitted an invitation to breakfast from Cyrus Eaton, the maverick anti-Cold War billionaire (founder of the Puqwash Peace Conference and winner of the Lenin Peace Prize). They led us, lights flashing, to Mr. Eaton’s estate where he showed us the prize steer Khruschev had sent him and served us an elegant, celebratory breakfast. (The hitchhiker we had picked up kept his mouth shut and stuffed his coat with biscuits.)

We returned to campus welcomed as heroes by many, and buoyed by enough success to ignore the others. We went back to class rumpled but renewed, having left the incubator of college for the larger, chilly world; amazed and exhilarated that we had created something directly out of our imaginations and effort.

We had pressed the world and felt it yield.

Several years later, at a Yale symposium on the History of the Peace Movement in America, SDS activist and future California State Senator Tom Hayden traced the beginning of the modern student peace movement to the Grinnell 14’s Washington trip.

Generous, perhaps; but we all do still believe that Grinnell played its part.

THE GRINNELL 14

Mary Lou Beaman (Sarah Beaman-Jones)

Bennett Bean ’63

Terry Bisson ’64

Bayard Catron

Jack Chapman ’64

Celia Chorosh (Segar) ’63

Peter Cohon (Coyote) ’64

Ruth Gruenewald (Skoglund) ‘63

Mike Horwatt (Group Spokesman) ’63

Curt Lamb ’64

Mary Mitchell ‘62

Mike Montross ’63

James Smith ’64

Larry Smucker ’63

THE HOME TEAM COORDINATORS:

Phil Brown ’64

Ken Schiff ’64

With deep gratitude to the many who contributed to this story, and with respect which has lasted to this day.