My dad played music a lot when I was a young child. He would come home from work and put an album on his record player, change out of his uniform and drink a beer while he listened. Usually, his listening fare was show tunes or big band music. On occasion, he would play a Nat King Cole record or something from the Ink Spots. Sometimes, he would put on a record by the folksinger Burl Ives. On the weekends when my mom was out shopping, he would play Hank Williams, Johnny Cash or some other country and western artist. My mom wasn’t a fan of country music back then. Of all the music he played, my favorite back then was Burl Ives; his easy vocals and simple guitar playing pleased my young self.

Little did I know back then that Ives had been a leftist at one time. Nor did I know he betrayed his friends and comrades during the McCarthy era, denouncing his leftist political beliefs and naming names to a congressional subcommittee. One assumes Ives took this action to stay out of prison and in the hope his career would blossom. He was correct on both counts. Like other artists, performers and writers in Hollywood and the music industry who decided to cooperate with the forces of reaction of the time, Ives traded his friends (and a fair amount of his integrity) for a modicum of success and a stay-out-of-jail card. History tells us that several other artists and the like who didn’t betray their friends or allegiances were not as lucky.

One thing history was never really clear on, though, was how the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Congressional investigators were able to determine which artists to pursue. How did they know which musicians attended study groups run by members of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and how did they know which ones were actual members? How did these investigators know who these artists’ friends were? What data did they use to decide who to call before Congress and/or threaten with imprisonment?

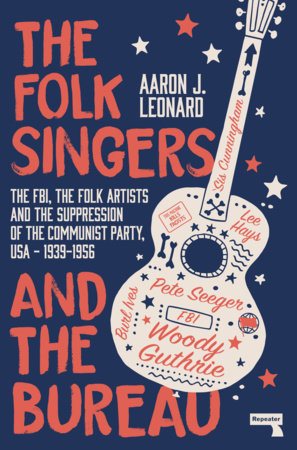

Historian Aaron Leonard’s latest book, titled The Folk Singers and the Bureau, takes on these questions. Utilizing FBI files, newspaper clippings, interviews and plain old research, Leonard has composed a tightly written, in depth exposé of the lengths the federal government went through to destroy left-leaning folksingers in the middle part of the twentieth century. Leonard, who appears to have made revealing the excesses of the FBI and other law enforcement agencies’ investigations against leftists his editorial focus, has turned in another relentlessly detailed and researched text on the subject. His two earlier books focused on leftwing revolutionary organizations—most specifically the Revolutionary Union and the Revolutionary Communist Party. This work takes on a more popular and better-known group of individuals—US folksingers like Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Josh White, Lee Hays and many others.

In telling this story, Leonard describes a government driven mad from a fear of communism and of individual zealots whose pursuit of those they considered enemies knew no shame. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s megalomania and paranoia is a driving force behind the persecution of these folksingers, while US media outlets and certain politicians are the ones who fan the flames. It is clear from the investigative documents Leonard quotes that the humanity of those the FBI was pursuing was unimportant. Indeed, the victims’ families and personal fragilities were fodder for intimidation and blackmail, but never for concern. The surveillance often went beyond stakeouts and planting informants at meetings, performances and rallies; sometimes it stepped over into straight out harassment and snitch jacketing, or falsely planting rumors that the subject was working for the FBI.

Many of these tactics continue today in government investigations of activists in the climate change movement, Black Lives Matter, leftist organizations and even in some progressive organizations allied with more radical groups. Residents of today’s United States live in a nation driven by a demented vision championed by a president who occasionally seems to have little sense of the real world while being consumed with his own hubris. In such a world, The Folk Singers and the Bureau provides the reader with a reminder of what the government is capable of doing to those who popularize a vision that runs counter to a capitalist economy, its war and its racism. Aaron Leonard’s works continue to shed light on the paranoiac police state known as the United States of America. The Folk Singers and the Bureau expands his field of research to the world of popular entertainment.