On May 29th, in response to growing protests in Minneapolis, MN, following George Floyd’s murder, President Trump tweeted, “When the looting starts, the shooting starts.”

Trump failed to inform his twitter followers that the term had originally been used by Miami police Chief Walter Headley in 1967 during hearing about crime in the city. His comments drew strong opposition from local civil rights leaders.

Om September 1st, Trump visited Kenosha, MN, surveyed damage from looting and arson that followed the police shooting of Jacob Blake. He ranted, “The fact is that we’ve seen tremendous violence and we will put it out very, very quickly if given the chance.”

In a follow-up conversation with Fox News host Laura Ingraham, Trump defended police officers who shoot unarmed Black people to golfers who “choke” and miss a three-foot putt. “They choke. Just like in a golf tournament, they miss a three-foot putt,” he insisted.

The concept of “looting” has a long history. Its origin in the Sanskrit term “lut” that meets “to rob” and entered the English language in 1788 as a word for plunder and mayhem.

However, the word “looting” is used to prejudice consideration of unrest as a rational, if enraged, critique of unequal social relations. Invoking the term looting often prevents acknowledgement that such actions represent a revolt of the oppressed.

For some, however, the stealing goods and destroying property are direct, pragmatic strategies of wealth redistribution. Some claim that such distribution can improve – if only temporarily — the lives of the poor. Going further, such acts of protest are direct attacks on the common belief in the absolute sanctity of private property and ownership. Looting have helped people gain a political voice and regain their humanity. In addition, they can help participants by sharing the “loot” expropriated and, in some remarkable incidences, build viable political organizations.

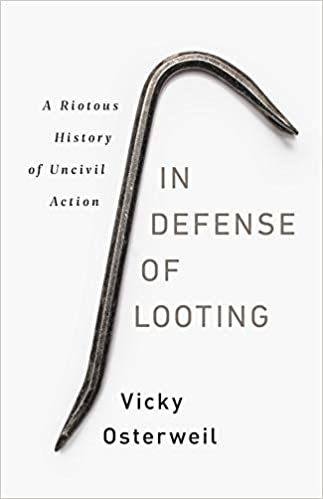

Vicky Osterweil, in her provocative new book, In Defense of Looting: a Riotous History of Uncivil Action, argues that looting is a “radical and powerful tactic for getting to the roots of the system the movement fights against. The argument is not that all instances of looting increase freedom, are righteous or politically anti-propertarian.” Most pointedly, she argues:

If protesters hadn’t looted and burnt down that QuikTrip on the second day of protests, would Ferguson [MO] be a point of worldwide attention? It’s impossible to know, but all the non-violent protests against police killings across the country that go unreported seem to indicate the answer is no.”

She notes that looting and burning of a QuikTrip in Ferguson is but one of a growing number of such acts of protest. In Brooklyn, NY, the killing of Kimani Gray in 2013 led to the looting of a bodega and a Rite Aid store  as well as innumerable similar actions throughout the country over the last decade.

as well as innumerable similar actions throughout the country over the last decade.

***

Looting is a form of violence as social protest that sometimes can lead to social change. It is long linked to riots as a tactic to challenge state authority and, especially, the authority of policing. In the modern era, the rise of the police force date from the 17th century English night watch and continued through European colonization of North America, including the looting of Native Americans lands, goods and lives as well as the slave patrols of the plantation South.

People forget that looting is an all-American practice. The 1773 Boston Tea party was one of the first acts of violent civil disobedience that led to the Revolution. Colonial protesters climbed aboard three British ships and dumped 342 chests (45 tons) of tea, worth an estimated $1 million, into Boston Harbor.

Looting is long tied to anti-Indigenous and anti-Black oppression that dates from the nation’s very origins. In the South slave patrols went after runaway slaves and institutionalized race policing that, with city police departments, have sought to suppress Black and other people of color.

In 1838, President Martin Van Buren sent 7,000 soldiers to remove Cherokee Natives from their homes in Georgia. The troops forced the Cherokee into stockades while whites looted their homes. By 1840, tens of thousands of Native Americans were driven off — and looted — their land.

Throughout the 19th century urban working-class riots, often accompanied by looting, were common. For example, the 1857 New York gang war that pitted the Dead Rabbits against the Bowery Boys was a gang war between immigrant, working class men and boys that not only led to a citywide battle but widespread looting and pillage.

Worse still, the 1863 Draft Riots were a mass uprising of mostly poor and immigrant whites, many of Irish descent, opposing the imposition of the draft to wage the Civil War. The rioters were afraid that Union victory would put an end to their jobs, so they refused the draft. It witnessed the looting of stores, setting fire to homes and businesses, attacks on the police and soldiers, and beating and murdering innocent civilians, many African American civilians; the official death toll was 119.

Urban riots throughout the 19th century became increasingly race identified confrontations – of Blacks vs. local police and the National Guard. However, the use of the U.S. Army’s 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions to suppress the 1967 Detroit Riot.

In one of the most illuminating chapter of her book, Osterweil details how in the wake of the riots in Watts (1965), Detroit (1967) and Newark (1967) radical organizations emerged that carried forward the inchoate demands of the looters. For example, in Los Angeles, militants formed the Black Congress; in Newark, the movement formed the Community for Unified Newark (CFUN); and in Detroit, Black nationalist established DRUM (Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement). This process continues as indicated in formation of Black Visions, led by African American gender nonconforming women, in the wake of George Floyd’s killing.

And then there was black out of 1977 that swept New York City. Neighborhoods like Crown Heights and Bushwick were devastated; in Crown Heights, 75 stores on a five-block stretch were looted, and in Bushwick 35 blocks of Broadway were destroyed with 134 stores looted and 45 set ablaze. In the Bronx, 50 new Pontiacs were looted from a dealership.

***

The Los Angeles riot of 1992 followed the acquittal of the four police officers for the beating of Rodney King. The riot led to more than 1,000 buildings being destroyed with damage nearing $1 billion and that Koreatown suffered $850 million worth of damage, half was on Korean-owned businesses. More troubling, 64 people were killed — 2 were Asian, 28 were Black, 19 were Latino, and 15 were White; 2,383 people were reported injured. No law enforcement officials died.

In 1992, as the riots in LA raged, Bill Clinton, then governor of Arkansas, warned: “People are looting because they are not part of the system at all anymore.” He added, “They do not share our values, and their children are growing up in a culture alien from ours: without family, without neighborhoods, without church, without support.”

One can only wonder what Clinton would say in 2020 as an ever-growing number of Americans are feeling that their link to the “system” seems increasingly tenuous as Covid-19 takes its toll, the economy flounders and evictions increase. Is more looting on the historical agenda?