Let this be a lesson to you all: Don’t try to con teenagers when it comes to spring break. It can be done, of course, but the consequences are bound to be unspeakably harsh.

Let this be a lesson to you all: Don’t try to con teenagers when it comes to spring break. It can be done, of course, but the consequences are bound to be unspeakably harsh.

This winter when we were all sitting around the table in our house in Oregon City, facing the prospect of six more months of gloom and rain, the four of us decided that an escape to someplace sunny, dry and hot in April might recharge us, making it possible to trundle on through the sunless Oregon spring.

For years, I’ve wanted to spend some time in the Mojave desert. I’ve driven across its basins and mountains many times, but always on the way to or from someplace else. There was a spot on the map that had long intrigued me: Twentynine Palms, California, a small desert town at the northern entrance to Joshua Tree National Park. I suggested this as a potential destination. Apparently, when I said Twentynine Palms, our kids, aged 19 and 17, heard Palm Springs, that sprawling cancer of a city 50 miles to the south. They were enthused for once and, ridiculously, I did nothing to discourage their fantasy.

Dumb move on my part.

We flew from Portland to Sacramento to Ontario, California. I detest airplanes and this was the first time I’d flown since 9-11. The rest of the family, frequent fliers all, had already become inured to the groping searches, the demands to remove shoes (which in our son Nat’s case could, depending on the shoes, be noxious event in itself), the ceaseless checking for photo ID, the seizure of knitting (though not crochet) needles and nail clippers. As it turned out, self-consciously liberal Portland conducted the most intrusive searches of the three cities, with the lines slushing forward at the pace of the Wisconsin Glaciation.

Having arrived bleary-eyed at PDX three hours early, I had a chance to watch dozens of searches and try to make sense out of who was being singled out and why. By and large the pat-downs at the gate seemed to be dictated by a simple quota system-ten to twelve individuals per flight, roughly twice as many men as women. (Nat and I were searched four times in four flights. Our daughter Zen once. Kimberly not at all.)

A demographic note. In Portland, nearly all of the people charged with doing the searches were black; most of us being searched were white. It was a fetching irony, and a situation that might do more than anything else to instill popular resentment toward the relentless incursions of the Surveillance State. There’s nothing like a good strip search to convince even the most stalwart Republican that perhaps Ashcroft has gotten a little carried away.

I’d say one out of four passengers who’d been selected for inspection huffed, pouted and acted indignant, many of them snapping at the searchers with boisterous declarations of their patriotism. And, for the most part, the searchers kept their cool, trying to keep the searchees calm enough so that they wouldn’t be booted from the airport as, to give an old phrase new meaning, “flight risks”. Many of them snickered, shook their heads and imparted knowing winks to their colleagues. One could easily imagine situations where blacks who objected to similar searches by cops on the shoulder of, say, the New Jersey Turnpike ended up being hauled off to jail or to the morgue.

Ontario was a different story. The searches here were more cursory. Instead, this rather puny airport had opted for a robust show of military force, with more than a dozen (all white, as far as I could tell) national guard troops prowling the corridors in full combat gear, including M-16s, giving young women the once over. It had the creepy atmosphere of the airport in Buenos Aires during the height of the Dirty War.

From Brand Hell to the Devil’s Garden

We headed east on Highway 10 out of Ontario. This must be one of the blandest roads in America: a smog-drenched corridor of car lots, cloned subdivisions, billboards promoting phone sex and Indian casinos-the latter day rubble of the California dream.

The monotony is broken only by the brooding hulk of the San Bernardino Mountains and by Cabazon, home of the giant truckstop dinosaurs featured in PeeWee’s Big Adventure and the Desert Hills Premier Outlet Mall.

If you thought we’d drive right past Cabazon, you don’t know our daughter, who as a taskmaster would shame even merciless old Ward Bond from Wagon Train, the sixties tv western sponsored by the Borax Company, the mining conglomerate that has done more than just about anyone to ravage the outback of the Mojave.

This may be the world’s hautiest outlet fashion mall. It’s an orgy of brand retailing wrapped in a kind of faux-Venetian architecture. The stores hawk discards from an array of designers, from Donna Karan and Gucci to Barney’s of New York and Versace. In the Giorgio Armani Exchange a near brawl broke out among about 20 Japanese teens, each fighting for possession of as many of the impossibly tight tops as they could grab. Still, most people seemed mainly interested in toting around a bag with some elite store’s name and brand on it. Others, quite sensibly, headed straight for the Godiva Chocolatier.

The whole scene is so overwhelming that it’s possible to imagine that even Naomi Klein-the Boadacea of the battle against Brand Culture-might feel faint at the prospect an afternoon trolling the aisles. I finally took refuge in the Bose speaker store, found a cd by The Kinks and cranked up You Really Got Me loud enough to awaken the San Andreas Fault.

About 20 miles outside of Cabazon we came to the junction of I-10 and Highway 62. In the notch between these roads, there’s a patch of Sonoran desert known as the Devil’s Garden. By most accounts, it was once to the world of American cacti what the Hoh Valley is to temperate rainforests: the most exuberant expression of the biome on the continent.

In 1906, George Wharton James, in his book Wonders of the Colorado Desert, described the strange cactus jungle this way: “When we find ourselves on the mesa, we begin to understand why this is called by the prospectors ‘the devil’s garden.’ It is simply a vast, native, forcing ground for thousand varieties of cactus. They thrive here as if specially guardedI know of no place where so many are to be found as in this small area near the Morongo Pass.”

Twenty-five years later it would all be gone, plundered by Los Angeles real estate developers–the great barrel cacti and ocotillo uprooted for replanting in the obligatory cactus gardens that adorned nearly every house in southern California.

The passing of seventy years has done little to restore the damage. There should be a sign somewhere commemorating this spot as one of the great battlefields in the history of environmentalism, the Antietam of the desert preservation movement.

The cause of the desert was taken up by one of the great unsung heroes of the environmental movement, Minerva Hamilton Hoyt. Hoyt wasn’t a female John Muir. She wasn’t a mountaineer or a desert rat. She was an LA socialite.

Hoyt proved to be tenacious, visionary and connected. She soon got FDR’s ear, and more importantly, face time with his Interior Secretary, the original Harold Ickes. Ickes pere was a titan of his time, nothing like his son, Harold Jr., the weasely hatchet man of the Clinton White House. Ickes took Hoyt’s maps and within three months had withdrawn from private looting more than a million acres of land from Morongo Pass east to the Colorado River, then still a river in flow as well as name.

Over the years the mining firms and ranchers and Pentagon whittled away at the monument, seizing anything of commercial or strategic value. In 1993 when Clinton and Dianne Feinstein pushed through the California Desert Protection Bill, creating Joshua Tree and Mojave national parks, it turned out to be a far cry from the original vision hatched by Hoyt and Ickes. The deal was another Clintonesque win-win gesture, designed to grab headlines but save precious little.

Highway 62 is a 175-mile-long arc of road cutting through the heart of the Joshua tree country from Palm Springs to the Colorado River town of Earp, at the foot of the Whipple Mountains. The road climbs up out of the carbon monoxide-glutted haze of the Coachella Valley past the shadow of Mt. San Gorgonio onto what the locals call the Hi Desert and we know as the southwestern tip of the Mojave. We moved quickly past the towns of Morongo Valley, Yucca Valley and Joshua Tree, increasingly inhabited by the service workers for Palm Springs, who have been priced out of the absurdly inflated land values in Coachella Valley.

The original Highway 62, now buried under asphalt and the ubiquitous DelTaco drive-thrus, was known during the prohibition era as the Bootlegger’s Highway. At night, giant Joshua trees (including the largest known tree in existence) were soaked with kerosene and lit on fire, like giant tiki torches, to mark the perilous path to John Shull’s place near Indian Cove canyon. Shull was the clubfooted genius of Mojave moonshine, whose potent concoctions found their way to the speakeasies and casting rooms of LA.

It was after nine when we finally pulled in at the Inn at 29 Palms, a small resort, perched on the edge of a fan palm oasis, consisting of about a dozen nicely kept adobes built in the 1920s. There were immediate remonstrations from the backseat. Apparently, this wasn’t exactly (or even remotely) the kind of spring break getaway our kids had in mind. Their worst fears were confirmed by the hotel: no phone, out of cell range, no video games, no nearby shopping district and a television the size of a cantaloupe.

Revenge would be swift and unsparing and it would come in the form of Palm Springs.

Windmills and Liberace’s Bathroom

Kimberly and I awoke early to golden sunshine, the insistent call of a Scott’s oriole and unremitting demands for reparation.

“Yes?” I say.

“Time to go.”

I was being double-teamed now. Even Nat, once a reliable hiking companion, had defected.

“Go? Go where?”

“Palm Springs.”

“Good lord. Why?”

“There’s nothing happening here.”

“Precisely.”

“There’s nothing to do.”

“Take a hike. Read Twain. Bask in the sun.”

“You won’t let us. Skin cancer, remember?”

Check-mated again. Palm Springs it was.

Of course, this elegant bit of sophistry didn’t stop Zen from trying to attain in a matter of five days the same bronze tones Georgia O’Keefe acquired after a period of 60 years of sustained exposure to desert sun. She got the requisite tan, a kind of living proof for her running mates back in soggy Eugene that she had made a desert pilgrimage, and, after day three, a nasty case of sun poisoning, which, naturally, didn’t deter her in the least from two more days of noon-to-dusk broiling.

Palm Springs has been a spring break haven ever since Troy Donahue stripped his shirt off and presided over a poolside rave-up in Palm Springs Weekend. But I blame our kids’ obsession with the place all on Carson Daley and those MTV spring break hot tub shows. And why not.

From the west, the entrance to Palm Springs is heralded by a sprawling wind farm, operated by the Wintec Corporation. Simply put: it’s a blight masquerading as an example of enlightened environmentalism. More than 4,000 wind mills clot the San Gorgonio Mountain pass, blotting the scenery for miles, and shredding untold thousands of migrating birds. Perhaps only the pesticide-sated waters of the Salton Sea, forty miles to the south, present a more lethal hazard to our avian cousins in this region.

Some of the windmills are 150-feet tall, armed with blades half the length of a football field. When fully-deployed, the three twirling arms of the windmills look like nothing so much as Mercedes-Benz hood ornaments. It’s certainly appropriate. By some accounts, the Coachella Valley boasts more Benz’s per capita than any other conclave of fat cats in North America.

First Palm Springs, then the Nuclear Test Site in Nevada. The radioactive wastes of the NTS are slated to become the next big windfarm. In a deal hatched between the DOE and Siemens Energy, and brokered by Nevada Senator Harry Reid, the blast site windfarm will consist of the 325 turbines whizzing out 260 megawatts of electricity.

There we have it. Windmills are a greenwashed form of political pork, big capital-intensive projects that spurt lots of money into the accounts of energy conglomerates (even nuclear firms), and keep people wired into the current utility system. Under green energy marketing, the energy brokers and utilities can even con consumers into paying more for each kilowatt of wind power, a feel-good green premium.

You can drive down the fog-curtained Oregon coast and find more solar panels than you’ll ever see here in the valley of perpetual sun, a place that could easily disconnect entirely from the power grid.

But it’s all about growth. Even the windmill power plant is getting into the real estate development business. Here’s how Wintec describes their new Green Mall project: “Most of the property has never been developed. A small portion of the property is improved with large utility grade wind turbine generators which have already become a large tourist attraction. The property is visited by several thousand tourists per can safely share the property, each complimenting the other. The property is well situated in the emerging commercial/industrial sector of the City of Palm Springs and enjoys a tremendous competitive advantage for commercial mall development.”

Shopping malls on previously undeveloped desertthat’s the kind of environmentalism that would have made Sonny Bono gleam with pride.

Of course, in a perverse way the contamination of what the landscape ecologists call the “viewshed” of the Coachella Valley may be all for the good, the dispensation of a kind of historical and ecological justice on the perpetrators of so much destruction and misery (not mention horrid cinema). After all, Palm Springs was always the favored desert colony of Hollywood’s most noxious right-wingers and their allies in the world of big business: Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Walter Annenberg, Frank Sinatra, Sonny Bono. Some of these early pioneers still survive deep into their dotage, such as the awful Hope, who seems to exist on some far-out kind of life-support system reminiscent of the devices in Frederic Pohl’s Gateway series of SF novels. Call it the mummification effect, where the process of decay unfolds so slowly it’s ever so difficult to detect the living from the dead.

Palm Springs (and its associated enclaves, Cathedral City, Desert Springs, Palm Desert and Rancho Mirage) is like a Chinese box of private enclosures, restaurants, bars, resorts, condos, spas, plastic surgeons, sex clubs. But at the heart of it all is, of course, the golf course.

Palm Springs is the Luxor of the hacking classes. There are at more than 100 courses in and around the city, all of them prodigious consumers of water, piped in from the poor Colorado River or sucked out of the Palm Springs aquifer. Back in 1987 (the most recent full-blown study I could come across), Palm Springs’ links soaked up a more than 130,000,000 gallons of water on an average summer day. It’s certainly much more than that now, with a new 18-hole course being bulldozed into the desert nearly every year.

In the arid West, turf watering accounts for up to 60 percent of urban water use. To keep its course a shimmering, almost surreal green, the Palm Springs Country Club extracts 430 million gallons of water from the aquifer every year-that’s five times the average for golf courses nationwide-and enough water to meet the daily needs of 11,000 people (and untold humpback chubs, the great, now vanishing fish of the Colorado).

Tiger Woods has a lot of explaining to do. After Woods does his penance for being a frontman for sweatshops, he needs to account for his shameless promotion of Palm Springs as a golfing Mecca for millionaires. Woods used to mouth pieties about bringing public golf courses back to urban neighborhoods and chafe about country clubs that catered only to whites. Now he pimps for one of the most exclusive-and exclusively white-enclaves in America, hawking courses that are built and maintained on the backs of Mexican immigrant labor. These workers are paid so stingily that they could toil for a month and not afford the green fees for a single round at many of the elite clubs.

Rarely have so many billions been mustered to so little purpose. There are few public spaces in Palm Springs, and its outliers, that aren’t solely geared toward channeling you into retail outlets or overpriced restaurants. We tried to eat on the cheap. But it was impossible to get away with a lunch for less than $50. Those producers at CBS should forget about using remote places like the Marquesas Islands as a setting for Survivor and instead hand the contestants $100 and see if they could survive in Palm Springs for two weeks-they’d make the Donner Party look like a bunch of vegans.

The art museum is decidedly third-rate and the city’s buildings fall victim to the same kind of civic-ordered mundaneness that destroyed Santa Fe and dozens of other towns across the New West. To find interesting architecture here you’ve got to venture up into the side canyons and foothills of Mount San Jacinto, and peer with binoculars into gated communities looking for the odd house designed by a Neutra, Venturi or Schindler, though in the case of Neutra this is becoming an uncertain propositon. Around the time we were visiting Palm Springs, Neutra’s famous Maslon House, built there in 1963, was being sold to a Mr Richard Rotenburg, who promptly tore it down. The former owner could have attached a preservation easement to the deed, but that might have lowered the value of the lot.

There are better ways to quench the voyeuristic impulse. Go to the bookstore and pick up two indispensable guides to the sleazier side of the valley, Jack Titus’s Palm Springs Close Up and Ray Mungo’s Palm Springs Babylon, which provide vivid accounts of the political, financial and sexual escapades of the city.

Palm Springs is where Nixon came to lick his wounds after resigning the presidency, Mamie Eisenhower to get tanked and Betty Ford to dry out. It’s also where JFK had his fateful assignation with Marilyn Monroe on March 25, 1962, at Bing Crosby’s estate.

It wasn’t supposed to come down that way. Frank Sinatra, who had shuttled dozens of starlets to the Kennedy brothers, had been expecting JFK to make his house a presidential getaway. Indeed, Sinatra had sunk a lot of cash into a new security system and a helicopter pad just for Kennedy’s benefit. Then pious Bobby intervened, citing Sinatra’s fruitful relationship with Sam Giancana, among other mobsters. Sinatra fumed and shifted his loyalties to the Republicans. In 1969, he hosted Spiro Agnew, who, upon arriving in town, announced to the press corps: “It’s nice to be in Palm Beach.”

One redeeming virtue of old Palm Springs is that it served as a relatively safe harbor for many Hollywood gays, from Rock Hudson to Liberace, who partied at places like the Desert Palm Inn and the New Lost World Resort (formerly Desi Arnez and Lucille Ball’s compound), which has become one of the most opulent gay and lesbian getaways on the planet. (Of course, the city was also a refuge of last resort for wealthy butchers, such as the family of the Shah of Iran. But out here that just comes with the territory.)

If gays were tolerated, the same can’t be said for other oppressed classes, such as Jews and blacks. Until the early Fifties Jews were permitted to stay in only one hotel in town and that one discreetly identified them with a “J” beside their names in the desk ledger. Blacks were simply not welcome at all, except as golf caddies, as Jack Benny discovered when he tried to book a room for his partner Rochester.

But the great Palms Springs dream is distilled to its essence in this passage from Mungo describing The Cloisters, Liberace’s house: “The house is across the street from a Catholic church, Our Lady of Solitude, where sandwiches are passed out daily to the homeless who loiter in the vicinity. Inside, Liberace’s toilet is a throne, with armrests and a high back done up in red velvet. The shower curtain features replicas of Michelangelo’s David, while the wallpaper is decorated with Greek couples fucking in every imaginable position. There is a Gloria Vanderbilt suite, a Rudolph Valentino room (Liberace’s middle name was Valentino, and the Great Lover was an early Palm Springs celebrity who made several pictures here in the twenties), a room wallpapered in tiger skin, a Marie Antoinette suite, a bath with mirrored walls and ceiling and a pool-sized Jacuzzi, and a collection of strange bric-a-brac and junk no thrift could unload, including plastic birthday cakes and a life-sized stuffed male doll with erect penis. Into this world he introduced his young escorts, took his pills and kept his cranky mother.”

Yes, those were the halcyon days; it’s all been downhill since.

The Oasis of Mara

Our little hotel sets beneath the Queen and Pinto mountain ranges on the northern edge of Joshua Tree National Park at the Oasis of Mara. This fan palm oasis used to be known as Indian Gardens, after the beanfields laboriously tended by the Serrano Indians. Mara is the name the Serrano gave to the place, meaning “place of small springs and tall grasses.”

The Serranos were part of the “toloache” cult, whose rituals were brought to life by psychedelic trips induced through the smoking of that noted member of the datura family, jimson weed. The hallucinations were induced primarily for religious rites, but they also had more pragmatic applications, such as to assure luck in gambling.

By most accounts, the Serrano tribe proved to be masters of a complex desert agriculture, cultivating beans, melons, gourds and Devil’s claw, a plant domesticated for use in weaving the tribe’s extraordinarily beautiful baskets. They also gathered the fruit of the fan palm and the sugar-sweet seedpods of the honey mesquite.

The Serrano, and their neighbors the Cahuilla and Fernandeno tribes, were pacifists and not uncommonly led by a woman chief.

This rooted and nonconfrontational mode of existence suited life in the desert, but became problematic when the more aggressive Chemeheuvi band of Paiutes showed up at the Oasis in 1867, having been driven westward from their homelands along the Colorado by Mormons and miners.

Life for these tribes under the Spanish occupation was miserable, but it got even worse when California became a state, especially after the gold rush. In 1851, California’s second governor, John McDougal, laid out the state’s genocidal gameplan: “a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct.” They were duly denied citizenship rights, voting rights and the right to testify in court.

California was admitted to the union as a free state. But this bit of enlightened thinking didn’t apply to Indians, who were routinely rounded up by ranchers, railroad companies and mining firms and made to work as slaves. This appalling situation was made official state policy with the passage of the Indenturement Act of 1850. Often slaughter accompanied enslavement. Indian parents were killed and the children kidnapped and sent off to work as slaves until the age of 30. The practice wasn’t outlawed until 1867, four years after the emancipation proclamation.

By 1902, the wars, disease, murders and kidnappings had taken their toll on the both Serrano and Chemeheuvi tribes. In that year’s census, only 37 Indians remained at the Mara Oasis. Today there’s little evidence of the Indians at all, except for a small cemetery of unmarked graves just west of the oasis.

From the Mind of Edgar Allen Poe

The Mojave isn’t easy to get a handle on. In general, it’s a high elevation landscape, relatively cool and wet, as far as deserts go-and surprisingly barren. The Sonoran desert, by contrast, is lower, searingly hot, parched and astonishingly diverse. In general. Because on the other hand, the Mojave also boasts the hottest spot in North America, the most sunken (Death Valley), and the driest (Baghdad, California).

The signature plant of the Mojave is the Joshua Tree, which an early desert ecologist described as springing full-grown from the mind of Edgar Allen Poe. Joshua Trees are monicots, grotesquely oversized lilies, with contorted limbs and trunks armored with spikes, which are used skillfully by the loggerhead shrike to impale its prey. They reminded me of the gruesome gibbets haunting the backgrounds of so many of Pieter Breugel’s paintings. Indeed, there is something deathlike about the Joshua tree. Rot is its signature feature, from the inside and out. Most mature Joshua Trees are hollow, the pithy core having flaked away.

These vegetable beasts (explorer John Fremont called them the most repulsive member of the plant kingdom) grow at an excruciatingly slow rate, something on the order of 1.5-2 centimeters per year. Even so, there are some gargantuan specimens in the park. One multi-headed titan in the Covington Flats is 40 feet tall and 14 feet in circumference, making it something on the order of 800-years old, about the age of the ancient Douglas-firs of the Oregon cascades.

Joshua Tree National Park contains a confluence of deserts, the meeting ground of the Mojave and the Sonoran, which in California, for obscure politico-etymological reasons, is referred to as the Coloradan.

Like most of the western parks, Joshua Tree was pretty well picked over by the mining companies before (and even after) it was set aside as a national monument and later a park. The fabled prospectors (and Joshua Tree had many) upon whom so much of the myth of western libertarianism has been constructed were in reality little more than hard rock sharecroppers for the big mining companies in San Francisco, New York and London. The most productive mine in Joshua Tree yielded little more than $2.5 million in ore, mainly gold. Certainly not worth all the bother and bloodshed.

On Tuesday morning, I went for a walk up Ryan Mountain, a relatively modest ascent of about 2,000 feet. Modest unless you are a flatlander, who spends 80 percent of his waking hours in front of a Macintosh at 200 feet above sea level. I huffed and puffed my way, being passed by a cadre of extreme runners who sprinted to the summit and back down before I had even made it half way. Trip on a cholla, I muttered, as they rumbled by.

They call it Ryan Mountain, after Jep and Tom Ryan, owners of the Lost Horse mine, who lived near its base in a house built by a nefarious character named Sam Temple. By most accounts, Temple was a sadist and unrepentant Indian killer, who served as the model for the murderer in Helen Hunt Jackson’s novel Ramona. I don’t know what the Serranos called this humpbacked peak. But it must have been a primo place to imbibe jimson weed.

The view from the top was worth the pain of the climb. Dust devils sprouted and zigzagged across the yucca plain below, which stretched for miles to the lavender-colored Little San Bernardino Mountains. The horizon was smudged by a dingy haze, bubbling up like steam from a witch’s cauldron, which signaled the presence of Palm Springs. I watched a ferruginous hawk lost in a lazy spiral beneath me, far too high to be searching for prey, apparently just joyriding on a thermal.

Lacking a stash of jimson weed or any other kind of hooch, I found a flat slab of rock, toasted by the sun, and fell asleep. But a few minutes later I was jolted awaked by a growl from the sky. A few hundred feet above me, six Apache attack helicopters cut northward across the turquoise sky. They were no doubt headed for the Marine Air Combat Training Center, a 596,000 acre bombing range located a few miles north of Twentynine Palms.

The Mojave is military land. During World War II, the Pentagon seized more than five million acres of the desert for military training grounds and bombing practice. The man in charge of running the show in the early days was none other than Gen. George S. Patton.

I can’t escape the sense that this place is haunted: so many thousands of practice invasions, carpet bombings, decimations of virtual armies and cities. This is where they practiced the bombings of Libya, Iraq, Serbia, Afghanistan and, now, Iraq once again.

And there have been many real deaths up there, too. Beyond the coyotes, antelope, lizards and desert tortoises wiped out by explosions or pulverized by roving columns of tanks, many young American soldiers have been lost. In training exercises during World War II, more than 1,100 men perished in the Mojave. Most died of dehydration. The brutal Patton limited the soldiers to one canteen of water per day as they were sent on forced marches across the sun-scorched terrain, apparently thinking it would toughen them up for the North African campaign. “If you can work successfully here, in this country,” Patton ranted to his troops, “it will be no difficulty at all to kill the assorted sons of bitches you meet in any other country.”

The man was sadistic and stupid. He graduated near the bottom of his class at West Point and it’s easy to see why. He apparently had no understanding of how intense heat and low humidity dry up the human body, conditions that would put even the best-conditioned athlete at risk of heat stroke. It’s a wonder more didn’t die.

But Patton remains an icon. Down the road at Chiriaco Summit, there is a museum honoring the general. It’s all hagiography and it must disgust many of the men who served under him. Most Americans know that Patton slapped two shell-shocked soldiers who’d sought refuge in an Army hospital bed during the Allies’ invasion of Sicily in August 1943. In the most famous incident, a sobbing Private Paul Bennett told Patton that his nerves had been “shot by the shelling”. Patton responded with a slap across the face and his infamous rebuke, “Your nerves, hell. You are just a goddamned coward, you yellow son-of-a-bitch. Shut up that Goddamned crying You’re going back to the front lines and you may get shot and killed, but you’re going to fight. If you don’t, I’ll stand you up against a wall and have a firing squad kill you on purpose. In fact, I ought to shoot you myself, you Goddamned whimpering coward.”

This quote is taken from the official report on the incident filed by Lt. Col. Perrin H. Long, head of the unit’s Medical Corps. Long’s report, which had been suppressed by Patton’s friend Gen. Omar Bradley, eventually reached Eisenhower, who was outraged enough to sideline Patton from his command for a few months.

The Patton cult persists in spite of this, a fact attested to by the thousands who pour into the Chiriaco Summit museum. Many even say the poor soldiers deserved the rough treatment. But one suspects that attitudes toward Patton would be different if it was more widely known that following a similar merciless logic the general had sent those 1,100 young men to their deaths in the desert–sacrificing them to the unforgiving Mojave sun and his own stupidity.

Disney Does Joshua Tree

I left Ryan Mountain and headed for Hidden Valley, a bewildering maze of rock south of the town of Joshua Tree. As I pulled into of the parking lot at the trailhead, I was accosted by a pair of coyotes standing in the middle of the road. They weren’t the hipster creatures portrayed in the poetry of Gary Snyder. These coyotes seemed straight out of a Dickens street gang. They had the scruffy look of expert pick-pockets and petty thieves.

I shouted at them that I wasn’t about to hand over my lunch and they should be ashamed of themselves for resorting to such undignified panhandling. They grunted and shuffled off, looking for a more sympathetic mark.

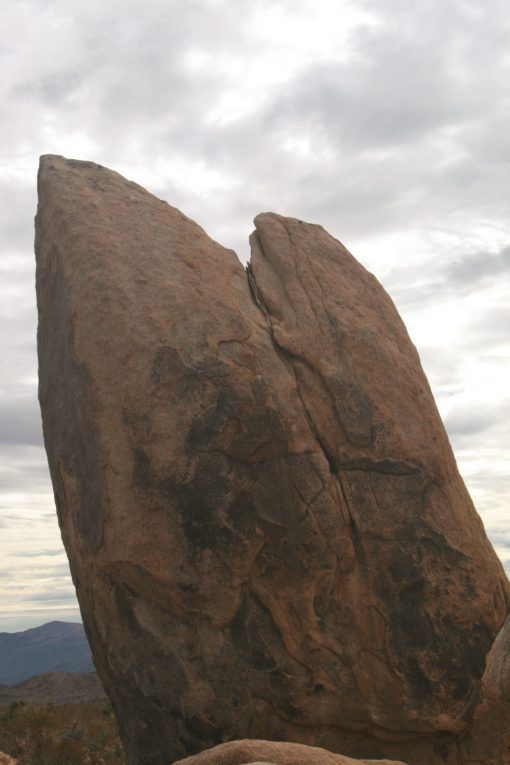

The place was a jumble of granite walls, strangely eroded slabs and domes of quartz monzonite, beaten soft by desert winds and almost fleshlike in color, glowing in the early evening sun with the hue of Bardot’s skin in that unforgettable opening shot of Contempt.

The narrow side canyons here created a moister microclimate that allowed for desert grasses to flourish. But its remoteness, sheltered conditions and forage also attracted the attention of a band of cattle rustlers known as the McHaney Gang. By all accounts, they ran a complex operation, involving rebranding, bribery, and a thriving interstate trade in both horses and cattle.

None of this did the idiosyncratic ecology of the valley much good. By the time the Park Service got its hands on the property the grasses were pretty much gone and, from photos taken in the 30s, so was nearly every other form of vegetation. Things have started to come back to life. I didn’t see many grasses, but the valley floor was crowded with yuccas, prickly pear, cholla, Joshua Trees, the strange two-headed nolina plant and, sunning herself on a boulder, a chuckawalla, the giant iguana-like lizard whose saggy skin looks three sizes too large for its body.

In a guide to the Hidden Valley nature trail, the Park Service pats itself on the back for having evicted the cows. But other parasites have taken their place, none so ubiquitous or annoying as the legions of rock climbers, in their insect-like gear, clinging from pastel-colored ropes to the sheer granite faces of the valley.

A couple of miles east of Hidden Valley is a small rockshelter with a panel of petroglyphs featuring fish and turtles on it. The Park Service calls them the Movie Petroglyphs. In October of 1961 some morons at the Disney Studios thought it would be good to feature the petroglyphs, originally pecked into the rock by Serranos and Paiutes, in a film called Chico: the Misunderstood Coyote. But the director didn’t think the images looked quite Indian enough, so he instructed the art department to paint over the glyphs and carve a batch of new figures. The Disneyfied images have all the verisimilitude of a Donald Duck cartoon. Even worse, the Park historian told me that the Park Service (50 years after the passage of the Antiquities Act, which made looting of Indian artifacts a felony) gave Disney the okay to paint over the rock art as long as they used “removable paint”.

The originals weren’t good enough. They stood in the way of something considered more cinematic and profitable. Now they are no more. Forget the tired theories of Frederick Jackson Turner: that’s the real metaphor for the history of the West in a nutshell.

Willie Boy Was Here

The Yucca Valley is the scene of one of the Old West’s last great myths, the story of Willie Boy, a young Paiute-Chemeheuvi Indian accused of two brutal killings. The white version of the story goes something like this. In 1909, a drunken Willie Boy got into a fight with a Paiute chief named Indian Mike in the town of Banning, slaying the older man with a six-shooter. Willie Boy kidnapped the chief’s daughter Isoleta, fled on foot east up to the Yucca Valley into the Hi Desert, dragging the poor girl with him as a hostage. When the young women began to slow him down, Willie Boy raped her repeatedly and then shot her in the back.

Eventually, so the story goes, he made his way to the Oasis of Mara outside Twentynine Palms, where only a few Indians remained, tending their beanfields near the giant fan palms. Willie Boy raided their huts for food and weapons and headed for the Pinto mountains. He was finally cornered in a small canyon and, in a final blaze of glory, gunned it out with the sheriff’s men. He wounded a couple of men, but finally turned the gun on himself.

Willie Boy’s exploits became a huge national story, because what passed for the White House press corps happened to be in Riverside, California at the time, covering William Howard Taft’s cross-country rail-trip promoting his latest piece of tariff legislation. Bored to tears by Taft’s bloated stump speeches the reporters seized on Willie Boy’s story, hyping it as the ruthless murder of an Indian chief and the kidnapping and slaying of an Indian princess. It dominated the national papers for weeks.

In 1969, the great Abraham Polonsky, who scripted Body and Soul and directed Force of Evil, whose career was wrecked by the blacklist, returned from his enforced exile to shoot a fairly good film about the grim story, called Tell Them Willie Boy Was Here, with Robert Redford and Robert Blake (now facing trial for the murder of his wife) once again playing the role of a misunderstood killer. In Polonsky’s version we are given a kind of reversal of the Wild Child story that François Truffaut (and later-to better effect–the German director Werner Herzog in The Mystery of Kaspar Hauser) was exploring at about the same time in his film L’enfant Sauvage.

In the Polonsky film, Willie Boy is an Americanized Paiute Indian who, upon being accused of committing a horrendous crime (the killing of the chief) based on little more than racial stereotyping, reverts into a kind of Hollywoodized version of Indian “savagery,” leaving behind a trail of blood worthy of a Jacobean revenge play.

Neither of these recitations share much relation to what really happened back in 1909, according to the local Paiutes who knew the story from the inside. The Hunt for Willie Boy: Indian-Hating and Popular Culture, by James A. Sandos and Larry E. Burgess, a brilliant new work of ethnohistory, sets the record straight. Sandos and Burgess use Indian recollections of the event and historical records to recreate what really happened. It seems that Willie Boy and the girl were engaged, a relationship that was not viewed warmly by her father the chief, who came after the young Indian one day with a gun. In a struggle, the gun went off and the chief died. There’s also no evidence that Willie Boy was a drunk. He and Isoleta fled together, hounded by one of the largest posses ever mounted. Sandos and Burgess believe that far from being raped and murdered by Willie Boy, the young woman was actually shot by one of the posse’s leaders.

Not far from where Willie Boy met his end nearly a century ago is a new Indian gaming casino, throbbing with neon, that seemed to be doing a brisk business taking money from military types and ranchers. Perhaps after all these years the Paiutes have exacted a certain kind of revenge after all.

Blame It on Reyner Banham

The Inn at 29 Palms is one of those wind-blown and sun-hammered places that could have appeared as the setting in a desert noir by Horace McCoy or Jim Thompson. Life at the inn centers on the pool and the adjacent restaurant, the where cooks conjure up the best food in the Valley, if not the entire Mojave.

That the word is out about the quality of the Inn’s food is attested to by the steady flow of local customers, a kind of daily parade of Hi Desert society: real estate agents, retirees from the Bay Area, gay couples, artists, cops and Marine Corps officers. The secret is the fresh vegetables, grown on the grounds, in a lovingly tended garden.

I spent a few hours by the pool flipping through Reyner Banham’s book Scenes from American Deserta. Banham was a prickly English architectural critic who settled in southern California in the 1960s and wrote a book that I greatly admire, Los Angeles: Architecture of the Four Ecologies. Growing up in Indianapolis, I’d inherited the Midwesterner’s reflexive hatred of LA, as a smog-clotted, car-obsessed, Sodom of narcissists, mountain-rapers and apocalyptics.

True enough, of course. But LA can also be great fun. And Banham’s book, like Robert Venturi’s on Las Vegas, provided an intellectual rationale for joining the party-and a key to understanding why going to LA, contrary to all my Hoosier conditioning, was worth the hassle of clogged freeways and damaged lungs.

As much as I liked Banham’s book on LA, I came to despise his take on the California deserts-not so much for Banham’s aesthetic, which in a way isn’t so different than Edward Abbey’s reveries about his boyhood haunts in Appalachia, as for what the forces he found beautiful and bounding with creative energy have done to the land and its human and ecological communities. In a sense, Banham practices a kind of hit-and-run aesthetic, rarely sticking around long enough to appreciate the consequences of the constructions he adored.

Banham had a taste for unplanned, accidental landscapes, studded with gadgets and gizmos in various states of use and disrepair, utility, fancy and ruin. That’s pretty much what this part of the desert was, an architectural free-for-all, a scattering of human structures with no real aspiration to be architecture. Naturally, that’s an empowering state of play for a critic, who sets himself up as an interpreter of chaos.

Banham is right about an important point: the deserts of California are not natural landscapes. Almost every square inch has been rearranged in some degree by human use or abuse, intentional and accidental. The myth of ecological purity is one that environmentalists pursue at their own peril. Indeed, such thinking led groups like the Sierra Club to support Senator Dianne Feinstein’s Mojave National Park legislation and promote it as kind of unblemished wilderness, when in fact it contains gold mines, cows, off-road vehicles and nearly every other contemporary curse of desert ecosystems.

But it’s one thing to recognize the imprint of humans, from the sophisticated desert agriculture of the Serrano to the riverside nuclear waste dumps of US Ecology, and quite another to fetishize it, as Banham so often does. He exudes about the nearby Salton Sea, for example, which is a man-made disaster, a kind of ecological root-canal gone horribly awry. Today, this water-wasteland, which Sony Bono tried to hawk into a desert Riviera, is a kind of toxic sludge pit, where the water sucked out of the Colorado River and irrigated through the fields of the Imperial Valley, returns to die, loaded with pesticides and the other chemical detritus from industrial agriculture.

Yes, as Banham notes, it’s possible to see a certain kind of strange beauty in the contraptions surrounding a gold mine, set starkly against a purple sky and blood red cliffs, and but you must also recognize that you’re staring a grave dug in the earth a thousand feet deep and a mile wide and know that hundreds of miles of streams, so precious in this arid land, have been fouled with cyanide. This is the context that undermines Banham’s aesthetic.

Banham once said that the thing he’d miss most about rural California is the air-shows. He liked Watsonville’s fly-in the best, which didn’t have any stars or celebrities or commercialized gimmicks. It succeeded as a kind of planned anarchy, a spectacle governed by no one. That’s not the kind of air show that goes on out here in the Mojave every day. Surely even Banham would have cringed at the black billion dollar monsters that prowl these skies.

Gram Parsons BBQ

On our final morning in the Mojave, I walked a mile or so up to the Park headquarters, rather indelicately entrenched in what was once the southern tip of the Mara Oasis, looking for information about the demise of one of rock’n’roll’s legendary bad boys, Gram Parsons. As I was talking to the park historian, the sky darkened, the wind whipped up, thunderclaps rattled the windows and, finally, the rains came down to wild cheers inside the ranger station. The rangers took turns prancing around outside in the downpour. “It’s been a year since we’ve seen rain like this,” one of them shouted.

Even an Oregonian like me, who had come to the desert to trade our 8 months of rain for a week of steady sun, could appreciate that this storm was a beautiful thing, indeed. The desert pulsed to life almost immediately at the first hint of the rain squalls. Even the small, reddish barrel cactuses seemed to perk up. And the smell of the Mojave after a drenching rain is an unforgettable pleasure, a scent flush with the pungent odor of creosote bush, mesquite and sand verbena.

As the skies lightened up, the ranger pulled out a topo map and pointed to the spot I wanted to visit: Cap Rock.

I’m of mixed views on Gram Parsons, the former member of the Byrds, founder of the Flying Burrito Brothers and originator of California country-rock. I like much of his music. He had a sweet, doom-ridden voice and he wrote some great songs, the beautiful Hickory Wind, for example. He re-introduced the steel guitar to rock, and gave new life to old tunes by the Louvin Brothers and Merle Haggard. On the other hand, he was a trust-fund rocker with a sprawling sense of entitlement who deliberately shattered his considerable talent and spawned a genre of seventies soft rock that haunts the FM airwaves to this day, from the humorless perfection of the Eagles to the formulaic crap of Pure Prairie League and Poco.

Parsons was born in Waycross, Georgia. His mother, Avis Snively, came from money. The Snivelys owned one of the largest orange groves in Florida and the Snively property in Winter Haven was turned into the Cypress Gardens theme park, a big pre-Disney attraction. His father, “Coon Dog” Connor, was also wealthy, coming from a family of retailers in Tennessee. These were rich but not happy people. By all accounts, both were drunks and battled depression. In 1958, Coon Dog blew his brains out with a .38 revolver. It was the first in a string of tragedies.

Soon thereafter, Gram’s mother married a fortune hunter named Bob Parsons and drink herself to death a few years later. The death was attributed to alcohol poisoning. Parsons, who had adopted Gram and his sister Little Avis, moved them to Florida and married the family babysitter a few months later. Gram always suspected that Bob Parsons had a hand in his mother’s death.

The Snively money bought Gram a draft deferment and sent him to Harvard, where he discovered hard drugs, developed a deeper sense of his own alienation, avoided any alliance with fellow southerner Al Gore and perfected his brand of post-rockabilly southern rock.

By 1968, Parsons was in LA, challenging Roger McGuinn for leadership of the Byrds. They collaborated on one masterpiece of country rock, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, before Parsons split with fellow Byrd Chris Hillman to form the Flying Burrito Brothers.

While in Southern California, Parsons became good friends with Rolling Stone’s guitarist Keith Richards. Evidently, Parson’s turned the Stones on to country music (for better or worse) and he and Richards would often escape up to the Mojave to listen to Chet Atkins records, sample a vast menu of drugs and scan the desert skies for UFOs.

Before going on tour in the summer of 1973 in support of his forthcoming solo album GP/Grievous Angel, Parson and a few friends went up to the small town of Joshua Tree, where they stayed in the Joshua Tree Inn, a nice but modest establishment on Highway 62. Parsons (who, for the curious, stayed in room number 8, which contains a plaque commemorating the event) went on a three-day binge of Jack Daniels, morphine and heroin. On the night of September 19, he overdosed, choked on his own vomit and died. His body was ultimately taken to LAX, where it was scheduled to be flown to New Orleans for burial.

Like most junkies, Parson tended to brood on his own death. And he repeatedly told his friend and road manager Phil Kaufman that when he died he didn’t want to be buried in the ground: “You can take me out to the desert in Joshua Tree and burn me. I want to go out in a cloud of smoke.” What follows is a screwball escapade that could have made a great Preston Sturges film.

Kaufman, one of the more outlandish characters in the LA rock scene, took it upon himself to fulfill Parson’s final wish. He borrowed an old hearse, dummied up some paper work and went to LAX, where he conned the people working for Continental Airlines’ mortuary services in turning over Parson’s coffin. Kaufman and his pal Michael Martin were so drunk at the time that they ran the hearse into a wall as they left the airport.

On the drive to Joshua Tree, Kaufman and Martin stopped at gas station to buy more beer and a couple of gallons of high test gasoline. “I didn’t want him to ping,” Kaufman later wrote in his madcap autobiography Road Mangler Deluxe.

The two ended up at Cap Rock, a bizarrely eroded dome of granite near Ryan Mountain. Kaufman says they stopped there because he was too drunk to drive any further. They unloaded the coffin and hauled it to a small alcove at the base of the rock monolith. Then Kaufman noticed headlights approaching and told Martin that it must be the cops. They quickly poured the gasoline over Parson’s corpse, lit it on fire, then sped away, across open desert.

They didn’t drive very far before Kaufman passed out. When they awoke the next morning they found themselves stuck in the sand. They had to hike to a gas station and get a tow truck to pulled them out. Their adventures weren’t over. Just outside LA, the hearse got into a multi-car pile up. When a California Highway Patrol officer ordered Kaufman and Martin out of the hearse, empty beer bottles fell to the pavement, and the officer put them in handcuffs. As the cop interviewed the other drivers, Martin slipped out of his cuffs, started the hearse and the two escaped.

At first the cops tried to blame the corpse theft and pyre on a satanic cult. But a few weeks later Kaufman turned himself in. He and Martin were fined $1,000. To raise the money, Kaufman threw a party. He called it the Koffin Kaper Koncert.

The spot where Kaufman ignited Parson’s coffin has become an informal memorial. There’s a large stone at the spot with the words Safe at Home (title of a Parson’s song) painted on it in red letters. People leave things at the site: syringes, plastic flowers, cds, St. Christopher medallions. Others have scrawled scraps of Parson’s lyrics on the face of Cap Rock itself.

I wanted to get a photo of the Gram Parsons BBQ pit from a small shelf on the rock above. There was only one way up. It involved a scramble over a scree pile, then a bit of free-climbing up a fissure in the granite. As I neared the ledge, I stuck my hand in a slot in the rock. Then I heard a kind of hollow buzzing, steady and insistent. I froze. I’d heard that sound before, though not quite so distinctly.

I looked down and saw about six inches from my hand a neatly coiled, blonde rattlesnake with the telltale slashes beside each eye, its erect tail chattering away like a drum groove laid down by Elvin Jones.

This was not your ordinary rattlesnake. No. This was Crotalus Scututalus. The Mojave rattler, a snake with a reputation for a foul temper and a deadly bite. Indeed, the herpetologists describe the Mojave’s venom, rather cagily under the circumstances, as “unique.” Uniquely poisonous. The Mojave’s venom contains a strange brew of more than 100 distinct neurotoxins, a concoction so complex even the mad scientists at Monsanto can’t duplicate it.

This all makes ecological sense. The Mojave is a harsh environment. The opportunities to nab a meal of delicious Kangaroo rat don’t present themselves that often. The venom (an offensive, not a defensive weapon) increases the likelihood of a strike resulting in a kill.

Time slowed down. And I began to calculate the odds, like some backcountry bookie. A phrase flickered across my mind: You’re more likely to be struck dead by lightning than to be bitten by a rattlesnake. It was strangely comforting. But only for a moment. Surely, those odds were calculated for the population of the country at large. Most people never see a rattlesnake. What were the odds of someone in my circumstance? Eyeball to eyeball with C. Scututalus, with me the intruder in his small patch of dust?

Those are precisely the kind of percentages they don’t give you, probably with good reason. It turns out the snake/lightning analogy is false, a bit of well-intentioned pro-rattler propaganda designed to keep the roughnecks from slaughtering any more snakes than they already do.

In fact, rattlesnakes inflict more than 8,000 bites on humans in the US every year. That’s a respectable number by any standard. The snake scientists say that 75 to 80 percent of rattler bites are considered “illegitimate”-an odd bureaucratic descriptor for a boneheaded move on the part of a human. Illegitimate touching of a pit viper.

One of the park rangers had told me that the last person to die of a snakebite in Joshua Tree was an English teacher who had led a field trip to the park with his students. Someone discovered a Mojave rattler lounging under a picnic table at the Jumbo Rocks campground. The teacher decided to use the snake as a prop (was he a fan of Harry Crews’ strange novel, A Feast of Snakes?), picked it up by the tail, began to discourse on the pacifist nature of the snake, when the rattler, quite properly, bit him in the stomach.

Of course, I too was a damn English major. And I had just made an illegitimate, boneheaded move. Used to scrambling over boulders and rockpiles in the rattler-free Oregon Cascades, where at worst you’re likely to be scolded by a pika, I hadn’t bothered to look where I was sticking my hand. It was all up Mister Scututalus, now.

But the little Mojave didn’t strike. He no doubt figured it wasn’t worth wasting his precious payload of venom on this bonehead, who could just as easily kill himself by slipping off the slick granite and smashing his skull on the makeshift cenotaph for a long-forgotten rocker. And for that I’m grateful.

We left Cap Rock and drove off into the desert evening, chasing those distant storms, behind a van bizarrely adorned with two whitewater kayaks (a true Banham moment), my foot tapping the floorboard to the beat of that most urbane of all bluesmen, Memphis Slim:

You may own half a city,

Even diamonds and pearls.

You may own an airplane, baby,

And fly all over this world.

But I don’t care how great you are,

Don’t care what you are worth–

‘Cause when it all ends up

You got to go back to Mother Earth.

Yeah, Mother Earth is waitin’,

And that’s a debt you got to pay.

Right you are, Slim. But not today.

All photos by Jeffrey St. Clair.

This essay is excerpted from Been Brown So Long It Looked Like Green to Me: the Politics of Nature.