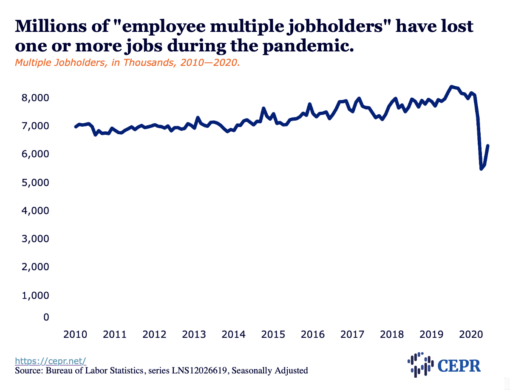

According to the Current Population Survey (CPS), 8.1 million employees worked one or more additional jobs in a typical week in 2019. As the figure below shows, the number of these “employee multiple jobholders” had been trending upward since 2013 before the pandemic hit. (We use the term “employee multiple jobholders” here because, as we discuss further below, the CPS does not capture “nonemployee multiple jobholders”.) Over the same period, the percentage of all employees who are multiple jobholders has been stable (at about 5 percent of all employees), so the increase in the number of employee multiple jobholders before the pandemic was driven by the underlying increase in employment.

Since the pandemic, the number of employee multiple jobholders has fallen precipitously. In April 2020, 5.4 million employees reported working one or more additional jobs, a decline of 2.7 million, or 33 percent, since 2019. In June 2020, the number of employee multiple jobholders rebounded slightly to 6.1 million employees (4.3 percent) but remains far below the pre-pandemic level.

There are two other surveys that offer insights into multiple jobholders that ask roughly the same questions as the CPS: the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Both have consistently reported somewhat higher levels of employee multiple jobholding (about 9 to 10 percent between 2013–2018) than the CPS (about 5 percent during the same period).

While the CPS is the primary official source of labor market statistics in the United States, there are some reasons to think that the ATUS and NHIS provide a more accurate count of employee multiple jobholding than the CPS, including differences in the survey reference period. (We discuss the strengths and weaknesses of these and several other surveys for estimating multiple jobholding in a forthcoming paper.)

If we assume that 9 percent of employees hold two or more jobs, then the actual number of employee multiple jobholders in 2019 was 14.2 million. If they lost jobs (no longer held one or more jobs) at the same rate as in the CPS, then approximately 4.7 million of them now hold only one job. This is without taking into account multiple jobholders who lost all of their jobs.

These numbers do not include multiple self-employed people who are not employees of anyone, but operate two separate businesses or perform additional “gig work” or informal side jobs in addition to their main self-employment activity. Thus, someone who operates a lawn maintenance business and a food truck is not counted as a multiple jobholder in the CPS, ATUS, or NHIS. Similarly, someone who works as an independent contractor for a tech company while also working as a hired driver, such as with Uber or Lyft, would not be counted as a multiple jobholder in these surveys.

It’s difficult to estimate how many employee and nonemployee multiple jobholders have lost one or more of their jobs over the last several months, but we can make a very rough estimate using the Survey of Household Economics and Decision Making (SHED), a nationally representative household survey sponsored by the Federal Reserve Board. The SHED uses a more inclusive set of questions about jobs and individual economic activities that better capture nonemployee multiple jobholding than the CPS.

In 2019, 26.5 million (16.4 percent of workers) in the SHED were multiple jobholders. Unfortunately, we don’t have 2020 data from the SHED on multiple jobholding, but if the 2019 data accurately captures multiple jobholding, and the number of SHED multiple jobholders has fallen by nearly 17 percent, half the rate as in the CPS for a conservative estimate, that would mean almost 4.3 million previous multiple jobholders have lost one or more jobs.

At least some significant share of multiple jobholders in the SHED are engaged in informal work and other seemingly minor economic activities. But as Katherine Abraham and Susan Houseman have documented, “[i]nformal work plays a particularly important role in the household finances of minorities, the unemployed, and those who report financial hardship.” Abraham and Houseman also find that, “[t]hose most likely to hold side jobs to supplement income, in turn, are the least likely to have critical benefits such as sick pay, health insurance, and retirement plans in their main job.”

Similarly, while income from online platform work is “not replacing traditional sources of family income,” researchers have found that, “[a]mong those who have participated in the Online Platform Economy at any point in a year, average platform earnings represent roughly 20 percent of total observed take-home income in any month of that year.”

Given the recent rise in COVID-19 cases, most people who can not work from home are safer not working. This includes many people who previously held more than one job, especially those multiple jobholders whose jobs involved close contact with others and/or multiple workplaces. Not working in one or more of these jobs, however, means a reduction in income from work, and, to the extent available, lost health insurance and other benefits tied to work.

The temporary Unemployment Insurance (UI) expansions included in the CARES Act have likely played a major role in stabilizing the economic security of previous multiple jobholders who have lost one or all of their jobs. In most states, regular UI replaced less than half of lost wages on average before the pandemic, but the CARES Act provides $600 per week in additional UI benefits. Regular UI also excludes many multiple jobholders with at least one self-employed or informal side job because it is limited to W-2 employees who meet certain work history and other requirements. The CARES Act established a Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) for certain workers who are ineligible for regular UI, including self-employed workers and others. PUA benefits are equal to one-half of state average benefits, so they vary by state and are relatively low compared to average state benefits.

Unfortunately, the $600 bonus expires at the end of July and PUA expires at the end of the year. Congress should act quickly to extend both. Additional improvements need to be made to both the structure and administration of PUA to ensure that it provides sufficient income without undue administrative burdens for multiple jobholders who have lost one or more jobs.

The CARES Act also includes new, temporary paid sick and family leave benefits for many employees who are unable to work due to their own illness, or because they have to care for a family member who is ill, or a child whose school is closed because of the coronavirus. The Act also provides similar benefits to self-employed people, but the mechanism for claiming them, a refundable tax credit applied to the 2020 tax return filed by the self-employed, means that these benefits are not available to self-employed people until next year.

While these and other measures in the pandemic-related legislation passed to date help millions of workers with multiple work arrangements, they remain insufficient and difficult to navigate. Policy discussions going forward should carefully consider how the current jobs crisis may affect these workers. Finally, federal statistical agencies need to improve the measurement of both employee and nonemployee multiple jobholding.

This article first appeared on CEPR.