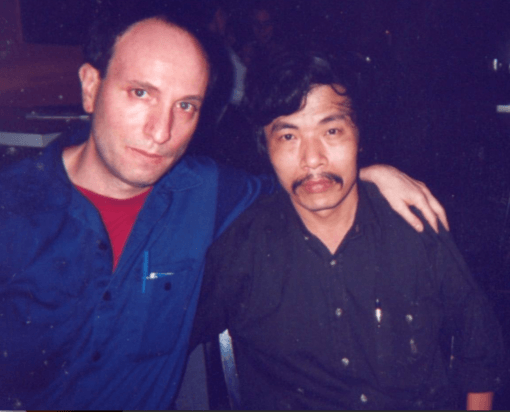

The author and Bao Ninh.

Three years after the Americans abandoned Vietnam, in the depths of the Jungle of Screaming Souls, NVA veterans search for the remains of men and women killed in combat. So begins The Sorrow of War, by Bao Ninh.

In 1995, when reading my paperback copy, I would fall into a trance, feel as if I were floating above my bed. What was happening, I did not know. Several months later, traveling in Southeast Asia, I invented reasons not to locate Bao Ninh.

Back home in New York I purchased the book in hardback; at the sight of Ninh’s dust jacket photo I saw those we hunted, and who hunted us. That night I dreamt my platoon was trapped, out of ammo, trying to escape.

In the fall of that year I wrote to Bao Ninh. Two months later his card arrived:

On the occasion of Christmas and the New Year, I am very glad to send you our warmest regard from Vietnam. I wish you and your family a new year full of happiness. I hope we will soon meet each other in Hanoi.

Summer 1998: I sat in a packed auditorium at the start of a writers’ workshop. Ten meters to my right, five Vietnamese writers waited to be introduced to the audience. Their remarks concluded, they walked single file to the exit at the rear  of the room. Instantly I jumped up, pushed past a gauntlet of crossed or outstretched legs. “Excuse me…excuse me…” I said, following my target.

of the room. Instantly I jumped up, pushed past a gauntlet of crossed or outstretched legs. “Excuse me…excuse me…” I said, following my target.

“Bao Ninh!” I stammered, as he neared the door. He turned around. The puzzled look on his face asked, “Who has called me? Which of the Americans knows my name?” From five meters we locked eyes.

“Moc Leby! Moc Leby,” he shouted, when I told him my name.

We rushed to each other with open arms. Ninh pulled me close, clapped my back once, twice, three times, as if I were a long-lost friend. Overcome by deep feelings, I sobbed uncontrollably. Ninh took my hand and me away. “No…I’m all right.” I said, still sobbing.

A tall, graceful woman drew near. Lady Borton provided medical aid to both sides during the war. A noted translator and writer, she had accompanied the Vietnamese delegation from Hanoi. Through her, Ninh and I spoke excitedly. Then Ninh explained he had to go. We could meet tomorrow at noon.

“Yes…thank you,” I said.

That night, an old recurring dream: the invisible spirit grabs my feet, yanks them straight up. I can’t move, I scream and struggle, then wake, overcome with dread. But this time, fighting back, I defeat the demon. Waking, I’m calm, free.

That afternoon, beneath a cluster of shade trees overlooking Boston Harbor, I sat cross-legged opposite Ninh. A muscular wiry man, then in his late forties, perhaps 5’ 6” tall, he sported a tousled head of jet black hair. A wispy Fu Manchu mustache adorned his upper lip.

For three hours, we talked through a second interpreter. My questions were academic: What did Ninh do in the war? Could he talk about NVA tactics? What did his platoon talk about when not in combat? What were his feelings about the Communist party? Ninh was thoughtful, patient in his replies.

Finally, I asked, “Is there anything I’ve overlooked? Is there anything you want to add?”

“Yes,” said Ninh, leaning forward, narrowing his eyes. Finally the American had asked a meaningful question. “The NVA were not robots. We were human beings. That is what you must tell people. We were human beings.”

I felt foolish, recalling too late that Ninh had spent six years in the Glorious 27th Youth Brigade. Out of five hundred, ten survived.

We stood up, dusted ourselves off, shook hands, and headed back to campus. Along the way, as Ninh stopped to smoke a cigarette, I delved into my wallet for the small photo of my platoon I’ve carried for thirty years.

On the back of it I wrote, “To Bao Ninh, these good men meant as much to me as yours did to you.” He held the photo, studied it, contemplated the young Americans, with their steel helmets, sun-bleached uniforms, hand grenades, bandoleers, and M16s. Looking up, his face inscrutable, he asked, “How many dead?”

“Only a few,” I said. “Many wounded.”

Ninh tucked the photo into his shirt pocket. I checked my watch. It was past three PM. We headed to the student cafeteria.

On the last day of the workshop Ninh stood center stage at the resplendent Harvard Yenching Library. Somewhat nervously, he bowed to the sizable audience, held his book close to his face, and began to read. The dreamy lilt of his tender voice was calm, lyrical. He could have been reading a lullabye. Ten minutes later Ninh closed the book, bowed to modest applause, and stepped from the stage. A handsome, vigorous man, and a heavy combat vet, Larry Heinemann, author of Paco’s Story, winner of the National Book Award, stepped up to read Ninh’s work in English. Clearing his throat, adjusting his shirt collar, Larry’s booming voice filled the hall with the sights and sounds of the horrific battle in the Jungle of Screaming Souls. The terror of the bombardment, wiping out an entire NVA unit, astoundingly dramatized, transfixed the audience. When Heineman smartly snapped the book shut, he motioned to Ninh, who now received thunderous applause.

That night, five Vietnam vets and the five Vietnamese vets, former NVA, met at a well-known Boston bar. Among the Americans: Andy, a heavy combat Marine; Larry Heinemann; Allan Farrell, a professor of languages and Special Forces colonel stationed in Laos; tall lanky Chris, an Army sergeant wounded his first month in country. The Vietnamese, each an established poet or writer, had spent years in combat. After two rounds of beer our grim mood gave way to easy banter.

I could not help but sit close to Ninh. Throughout the night he sat erect, sipped shots of whiskey, chain-smoked American cigarettes, hardly spoke. After a time someone asked him which side had the better automatic rifle. Ninh said the AK-47 was the superior weapon. Submerged, rain-soaked, caked by dust, or clotted with mud, it never failed to fire. But the M16’s small tumbling bullets caused terrible internal wounds and much suffering, and many losses.

Someone asked, “What was your saddest memory?” Ninh gazed into the curling blue smoke of his cigarette. Through Mr. Mau, he said, “Finding and burying our dead.” At that moment his face went sad and all were silent.

Toward 1 AM, as the high-spirited group continued to drink and jabber, I pantomimed to Ninh. He nodded agreement.

“Would you?” I asked Chris, offering him my camera. Chris had been shot in the neck. An angry, serpentine scar worked its way from his jaw to his collar bone. “Sure, Doc,” he said.

Ninh and I put our arms around each other. I barely managed to hold back my tears. Chris said, “Smile, Doc. C’mon, smile.” I barely managed to keep my jaw clamped shut. Afterward I took a photo of Ninh and Chris, and Chris choked up. Whatever Ninh felt he did not reveal it.

“Be right back,” I said, but once out of sight I walked to a nearby liquor store. “I’ll take that bottle, and that one, and that one,” I said to the clerk. “Can you wrap them, please?” Larry had mentioned that Ninh liked Jack Daniels.

No one noticed my stealthy return. During a lull at the table I carefully set out the gift-wrapped bottles. “Way to go!” said Heinemann. “Yo, Marc,” he said, thumping the table. “Make a speech. Thank the NVA for being here. Thank them for reading their poems. For telling their stories. Tell them the war has been over for quite some time, and we are honored and happy to be their friends.”

His words rang true. In war, we former soldiers, we Americans and North Vietnamese, would have shot each other on sight. Some things are hard to forget.

I handed the next-to-last bottle to Mr. Mau. The elder of the group, he’d fought the French, then the Americans. Everyone clapped and smiled at his eloquent remarks.

Then it was Ninh’s turn. He seemed genuinely surprised. “Open,” I said, pointing to the upright package. As he gently tore open the wrapping paper, the familiar stout bottle, the bold black and white label, came into view, and Ninh’s eye brows nearly flew from his head.

“Jack Daniels!” he shouted, and leaped from his chair. Clapping my back three times, he could barely contain himself. “Jack Daniels!” he shouted. “Jack Daniels!”

Earlier that day, Larry had told me the Vietnamese government had few resources to treat war trauma. For veterans and civilians, drinking was a common and acceptable way to sooth PTSD. Ninh, said Larry, had acquired a taste for the strong American liquor, which brought sweet relief from war and its sorrows.

I think of Ninh often. It’s been twelve years since that extraordinary coincidence, that turning point. To this day I don’t fully understand the meaning of my sobs. Some say it’s grief for my platoon, for the men and women we murdered. I don’t know. But I do know this: in peace time and war time, we are all human beings. All of us.