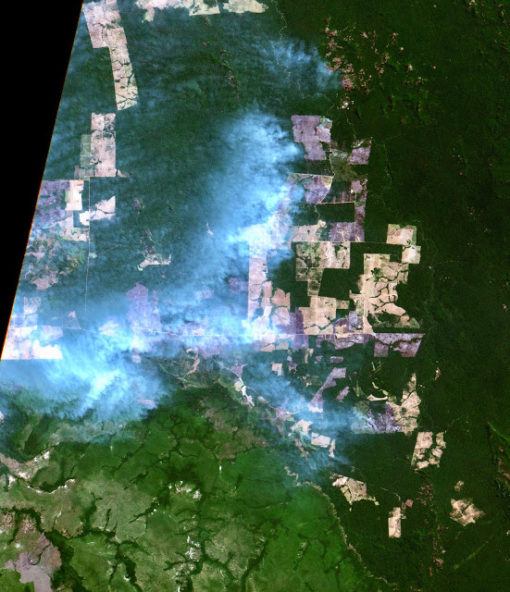

Fires burning the southern region of the Brazilian state of Para. INPE, Brazil, August 2019. Courtesy Wikipedia.

One of the lasting highlights of my teaching at the University of New Orleans in 1991-1992 was my travel to Brazil in January 1992 for a conference on climate change. This was a rehearsal for the June 1992 Earth Summit on Climate Change in Rio.

My conference took place in Fortaleza, a beautiful town in the state of Ceara in the northeast of Brazil. The conference passed quickly with meaningless speeches while the conference was besieged by indigenous people pleading unsuccessfully for a hearing.

However, I enjoyed a tour of the semi-arid countryside of Ceara. I sensed more than dryness and desert. I saw fragments of the Brazilian Atlantic forest. These moist woodlands are full of golden tall trees, marshes teeming with life, bleeding streams carrying away the red soil. Yet perpetual danger follows the trees, plants and animals. The loggers who devastated the Atlantic forest for more than 500 years keep coming, leaving a trail of plunder after them.

The asphalt road of our tour sliced through a flat region of small trees, bushes, goats and cattle grazing ranchland, and immense cashew plantations, producing Ceara’s number one cash crop.

We stopped in Caninde, a rural town celebrating St Francis, the ecology saint of the Catholic Church. Once in the St. Francis Cathedral, my eyes were immediately glued to banners.

The message in these colorful cloth banners was not what one would see in a church in North America. Here the burning issue was not hell or paradise or the ten commandments but liberation—the liberation of peasants from oppression. One banner said that the organization of the workers was terribly important for their emancipation; and another proclaimed that the concentration of wealth was the root of evil.

Clearly, the priest, a bespectacled, dark-skinned heavy-set man of medium height, was preaching a theology of liberation, trying to defend the poor by raising their consciousness. That understanding made the liturgy, in Portuguese, exceedingly important.

For a change, I said to myself, this part of our guided tour was appropriate to the spirit of sustainable development, the struggle of a few people of goodwill to help the rest understand that the Earth needs healing, not more ecocidal development. The theology of liberation had a soothing effect on my soul.

Later on we also went to a Cowboy Mass. It was the equivalent of an African-American spiritual / festival with all the passion, anger, and love of oppressed people recovering their freedom. Thousands of people enjoyed the passionate performance. You had the impression the entire crowd was becoming a single, huge person dancing and breathing the sounds of that emancipating music.

When the concert was over, they drove us to the Praca dos Romeiros (the Amphitheater of the Pilgrims), built during the drought of 1987. Just before we got into our buses for a return to Fortaleza, I read a message on the wall praising agrarian reform.

My field trip could not have had a better ending: Canindé was a city of liberation—or, at least, this was a place where liberation might have a chance.

In the Amazon

I took a late flight to Manaus, capital of Amazonas. I was determined to get an intimate view of the rain forest of Amazonia: a dream, a burning forest, the world’s largest, the “lungs” of the Earth, the laboratory of narrow-minded scientists, a huge wild frontier for the extraction of gold, timber, rubber and other “resources,” the home of feared Indians and despised Brazilians.

Amazonia is primarily untamed nature for countless species of plants, fish and terrestrial animals. But the Amazon rain forest is also a prize for Brazilians and international environmental politics, nationalism, and violence. It’s everything to all people, an unknown place for conquest, love, hate—and passion.

I found two biologists from the National Institute for Research in the Amazon, in Manaus, who invited me to go with them in their research trip into the fabled natural treasure of their country. They spoke very little English and I spoke no Portuguese, but the language difficulties were trivial to our common affection for the rain forest.

Spending a few days in the forest made a difference: Walking with the two biologists for hours in the solitude of the rain forest, swimming in the crystal clear waters of Acará, a small tributary of Rio Negro, sleeping in the deep darkness of the tall trees, brought me closer to thinking like those trees, those beautiful rivers, Amazonia.

The green, overwhelmingly green, nature of the Amazon—the trees reaching for the heavens and light — was burning in my mind. I climbed to the top of an observation point that brought me at the same level with the tallest trees in the reserve and the view of that most fertile part of the forest—usually the home of monkeys and other animals—was awesome.

A breeze lighted my sweat and fright from that height. The canopy of the trees, loaded with fruit and nuts, gives the impression of a fecund world covering a quiet but dense green interior between a brown leaf-covered land and the straight tall trunks of those trees, which have captured a space in the Sun. But even the quiet green first meters of the forest are a universe of complex biology and exquisite beauty.

There are trees that go straight up—nothing spectacular about that, you might say. Other trees send roots all over the land, the air, over and into other trees. In fact the land of the Amazonia I visited is but a complex web of roots and a couple of inches of decomposing leaves. Dead trees become the home for other trees, a variety of plants and animals. Nothing of that immense area in the rain forest is empty of life.

Rivers of creation

The rivers of Amazonia may be the answer to both the mystery and the fecundity of this part of the Earth, its overwhelming life, its beauty and taste of fruits, its flowers and, especially, its people and culture.

Manaus, for instance, sits on the mouth of the immense Rio Negro whose waters rise every June and July and give another chance to nature. Manaus is 1000 miles from the ocean and only twelve miles from the mighty Amazon River. I saw the coming together of the Rio Negro and Solimoes outside of Manaus. The two rivers meet but because their waters have different speeds (the Rio Negro moves at three kilometers an hour and Solimoes at seven kilometers an hour) and temperatures and density, the two rivers don’t mix for eighteen kilometers.

The Rio Negro’s dark waters are full of algae and Solimoes is full of silt that makes its water yellowish like mud. Solimoes, by the way, is a nickname for the Amazon River. But my first impression of the coming together of these two huge bodies of water—from the Verde Paradiso, a tour boat, in the background of the sprawl of industrial Manaus—is nearly metaphysical. Here nature, in all its perfection and in its utter contempt for humans trying to control it, is unsettling, though regulating the global environment. The sheer volume of the water of the Amazon River gives life to Amazonia. The fish and wildlife of the entire region, its climate and biodiversity, would probably wither and die without the Amazon River.

We ate pirarucu, a boneless fish caught in the Amazon River. This fish can grow up to 240 pounds. We visited two islands in the Rio Negro River, Teha Nova and Xiborena. They are sparsely populated by people who looked to me like converted Indians or caboclos, a mixture of Indians and Portuguese. These people fish and eat corn, casava and tropical fruit. In Xiborenathere are remnants of rubber and cacao plantations, so we can assume this island’s dark-skinned residents must have been, not too long ago, the slaves of white plantation owners.

Both islands are now Potemkin villages, places for a constant stream of tourists from Manaus. Their people live like European peasants of the nineteenth century but without any obvious signs of social unrest. Their homes sit on wooden poles to avoid drowning by the rising waters of Rio Negro. Each house has chickens, ducks, and dogs sheltered underneath its raised foundation. A number of these dark people sell trinkets to tourists. In Xiborenawe saw a beautiful patch of Victoria Regia water lilies.

The Subversion of Ecology

After my memorable trip to the meeting of the river gods in front of Manaus, I met an American biologist working for the National Institute for Research in the Amazon. He is tall, thin, wiry with a huge mustache. His name is Phillip Fearnside. He showed me a book he wrote in 1986 about the “human carrying capacity” of Amazonia.. He said he is the main opponent of the governor of the state of Amazonas who wants to repeal all environmental protection in Amazonia. He said he keeps his American passport but he is a permanent resident in Brazil.

Yet behind this man’s outward timidity and academic caution, there is a courageous defender of the Amazon rain forest. Being on the scene of ecological devastation, Fearnside has persistently criticized the obscene and Pharaonic development projects throughout Amazonia. He was a friend of the rubber tapper, Chico Mendes, who was murdered in December 1988 for slowing down the destructive work of the ranchers and other exploiters of the rain forest.

The careful ecological research of Fearnside has made a difference in the international struggle urging Brazil to consider that the Amazon is much more than a forest for charcoal, pig iron, silver, gold, timber, and cattle ranching. Of course, that is not what Brazil wants to hear about the Amazon. In fact, even Fabio Feldmann, one of Brazil’s most ecologically conscious Congressmen, whom I met in Fortaleza, is not willing to hear what foreigners say about the global value of the Amazon.

“Sustainable” development, yes, agrarian reform, no. Theory sounds sweet, even paradoxical to the new converts of the very model of industrialism that is unsettling the Earth. Meanwhile, ecology and green thinking, like the idea of sustainable development for the tropics, make for good dinner conversation.

Yet what happens in the Amazon and the other tropical regions of the planet reverberates throughout the world. According to the US Global Change Research Program, half of the Earth’s surface and three-quarters of the world’s population are in the tropics.

The tropics are part of a world of gigantic class inequalities between countries and within countries.

But, like my modest proposal for agrarian reform, my suggestion that the Europeans and North Americans ought to lift their debt sentence of death over Brazil and the rest of the Third World did not go very far. Violence has remained the order of the day.

Death without weeping

“I have seen death without weeping,” says the Brazilian writer Geraldo Vandre. “The destiny of the [Brazilian] Northeast is death. Cattle they kill, but to people they do something worse.” But death without weeping? Is this possible?

Nancy Scheper-Hughes, professor of anthropology at the University of California-Berkeley, spent several years studying the Brazilian Northeast and concluded that Geraldo Vandre was right.

The Brazilian Northeast, “land of sugar and hunger, thirst and penance, messianism and madness,” made death routine—particularly for “the children of poor families.”

Nancy Scheper-Hughes is unusual. She cares. But not many scientists do. They have shown an uncanny propensity in siding with power and doing its bidding.

Anthropologists and economists behind the genocide of indigenous people

In the case of the Amazon, scientists (mostly anthropologists and economists) have been the protagonists in the destruction of the fantastic ecosystems and indigenous societies of that immense forest region of Brazil, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru and Ecuador. The scientists’ destruction follows the model of centuries’ of experience from the European conquest of the Americas.

The Yanomami are one of the very few indigenous societies in the Amazon that survived the initial holocaust European explorers and Christian missionaries brought to the Americas’ non-European people in the fifteenth century.

Patrick Tierney, an American researcher, spent several years in the Amazon documenting the brutal fate of the Yanomami at the hands of Western experts and gold miners in late twentieth century. He paints an ugly picture of ruthless conquistadors parading under the garb of science and economic development for brutal personal ambition and unethical goals.

These academic crusaders, American and French anthropologists above all, came across the Yanomami hiding in the inaccessible forest and water wilderness of the Upper Orinoco River in the frontier between Brazil and Venezuela. That fateful encounter in the 1960s triggered another “conversion” against the Yanomami who have been portrayed as fierce people fighting ceaselessly over women.

Anthropologists and journalists and economists expanded on that lie and created a fictional Yanomami world so that they could subdue the gentle forest people with guns, diseases, development projects, and civil wars.

The Yanomami had also to deal with the diseases, bullets, and violence of thousands of gold miners and development agents of Brazil, Venezuela and the World Bank who invaded their land.

The indigenous solution

All the Amazonian indigenous people are, to some degree, Yanomami. Give them enough land, no more land grabbers, no more anthropologists, no more miners, no more World Bank economists and no more missionaries, and they can put together sustainability—in both nature (the rain forest) and their society. They are best qualified to heal the wounds of the Amazon and, in all likelihood, prevent the fearsome destruction of the rain forest. I smile at this thought.

But that may be a real “solution” to the inferno consuming Brazil and, in time, the rest of the world.

Indigenous people know the rain forest intimately. It’s their home country. Their wisdom is about the complex relationships of plants, trees, soil, animals, and rain. They grasp the small and gigantic ecological and political changes accompanying deforestation.

Alexander Zaitchik, an American reporter who investigated the burning Amazon, admires Brazil’s indigenous people, their knowledge of the land, courage and tenacity. He says that, “Before anyone was talking about climate change, they [the indigenous people of the Amazon] were trying to warn us.”

Indigenous people kept seeing the land grabbers leveling and burning their forests – for centuries. In just the last fifty years, fires and chainsaws destroyed a fifth of the rain forest, something like 300,000 square miles.

The fear, of course, is that this “epochal deforestation” could continue, in which case it would devour another fifth of the Amazon rain forest. Were such a calamity to take place, scientists warn, kiss life and Mother Earth goodbye.

A phenomenon known as “dieback” revenges human hubris and stupidity. It triggers auto-fire destruction of the remaining forest, with the result sending high to heavens a colossal amount of carbon. This carbon very likely will raise the temperature of the planet to levels inhospitable to life.

The prospects for such ecumenical holocaust are locked in existing policies. Forces in Brazil and elsewhere are adding daily fuel to the fires of a terrestrial inferno capable of eating the heart and the lungs of the entire planet Earth.

The new president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, is another Donald Trump. He is a mouthpiece of Brazilian landlords. He hates the natural world, indigenous people, and environmentalists. He is pushing through deregulation, giving a lift to land grabbers and killers of the indigenous people and the rain forest.

The UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, and the French president, Emmanuel Macron, said the fires engulfing the rain forest of Brazil constitute an international crisis. The Amazon needs international protection. In early 2019, some 73,000 fires were raging in the rain forest of Brazil.

I already said Brazilian government officials and politicians – long before the election of Bolsonaro in 2018 — resent any international discussion of the global ecological implications of the rapid despoliation of their fantastic Amazon rain forest. They say something like this:

“What we do with our ‘resources’ is our business. You, North Americans and Europeans, what right do you have to defend Amazonia from development? First of all, you chainsawed and clearcut your own forests, which themselves were substantial lungs of the Earth and sources of biodiversity at one time. Second, you taught us all we know about development. So, how are we to develop if we stop mining and burning the Amazon? And, furthermore, how are we to pay back all the money we borrowed from you without continuing to do the very things you now find objectionable?”

These questions could not be raised in the Fortaleza conference of 1992 or any other international climate conference – to this day in 2019.

My quest for putting agrarian reform on Fortaleza’s agenda troubled North Americans and Europeans to no end. But some of the Brazilians who listened to my talk said that without agrarian reform sustainable development would not have a chance. Besides, they insisted, Brazil should pull the rug from under the menacing plantation owners. These Brazilians knew that dividing up the huge farms of Brazil to modest sized-farms would save the Amazon from additional destruction.

Agrarian reform must become an integral part of avoiding a final dieback of the rain forest. With Trump and Bolsonaro in power, talks and policy changes in the US and Brazil are unlikely.

The real hope is now in the hands of Europeans and the UN. They need to create a World Environment Organization to protect the natural world from pollution and destruction. The decisions of such an agency could not be challenged by the corporate World Trade Organization.

Give the global Environment agency science, funds, and enough power to intervene decisively in cases like the fires of the Amazon. These fires are threatening the world. Second, change conventional economics boosting plutocracies to ecological economics boosting the perpetuation of a healthy society, environment and life.

The G-group of countries led by Macron (France, UK, Canada, US, Germany, Italy and Japan) already pledged to fund to Bolsonaro to the tune of $ 22 million for fire-fighting aircraft. This is a tiny by vital step in facing the Brazilian inferno for what it is.

Third, the indigenous people should also be given an opportunity to protect and safeguard the rain forest of the Amazon. They have the philosophical and ecological ways and means for doing that. They practice ecological civilization.

In 2018, they proposed to the UN the establishment of a corridor of indigenous lands from the Andes to the Atlantic. They assured the UN they would love to take care of this land.

Without a doubt, indigenous people have the knowledge, experience and love to protect that precious territory of Mother Earth – for all of us.