The most important political project of the modern era is an appropriately conceived and implemented eco-socialist Green New Deal. If done right, such a program would facilitate a transition away from the environmental and social pathologies of industrial capitalism to a world where people exist in symbiosis with the bounty of nature. If done wrong, it would be the last gasp of a relationship with the world that has brought a collective ‘us’ to environmental ruin.

The social problem is one of transformation, of taking apart the ways of doing things that aren’t working— and they are myriad, to create new relationships that work in concert with ‘the world,’ most particularly for its inhabitants. Given the trajectory of environmental decline, Western political economy will either be used to ring-fence rich from poor to leave the poor to their own devices, problems will be deemed unsolvable and decline will take its course, or capitalism will be overthrown and replaced with something workable.

The logical and humane path forward is to undertake a profound transformation of global political economy beginning with reconsidering the human condition— what meaningful existence entails, with a grounding in social justice. Given that background political and economic relations aren’t conducive to collective action, the path forward— should such be possible, will come through creating the conditions in both spheres for democratic participation.

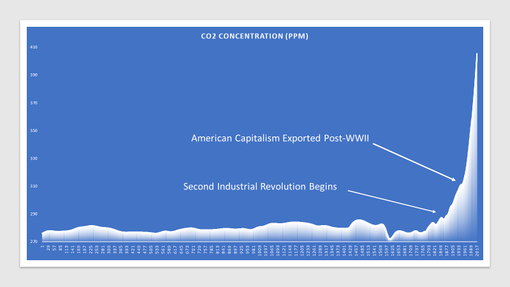

Graph: The sources of environmental decline are easy to identify through CO2 concentrations. First came industrialization. Then following WWII came the distribution of the American capitalist model around the world. Competition to control industrial inputs, e.g. oil and gas, led to most of the military conflicts of the modern era. The solution to current environmental woes is to stop creating them. Doing so would mean the end of capitalism. Source: ourworldindata.org.

Urgency comes through the relationship of existing ways of doing things to the rising costs of correcting environmental imbalances. The greater these become, the more cumbersome, and therefore the less politically likely, solutions will be. It is long-term environmental relationships that have been altered, meaning there are no quick fixes. The only guarantee is that whatever the costs in the present, they will be exponentially greater in the future.

Analysis and arithmetic argue against capitalist solutions to capitalist problems. Green production is neither green, nor can it replace existing dirty technologies fast enough to sufficiently reduce environmental harms. The issue gets to the heart of the capitalist conundrum. In a narrow sense, making products that are more environmentally efficient will lower their carbon footprint. In a broader sense, making clean products is intrinsically dirty.

The popular imagining of ‘the problem’ emerges from the logic of capitalism where intended outcomes are considered unrelated to unintended outcomes even though they 1) both emerge from the same production process and 2) are indissociable in the sense that one can’t be produced without the other. In like fashion, green technologies solve specific problems while creating others. When the total costs of green technologies are considered, what becomes apparent is that the broader logic is flawed.

The arithmetic problem is laid out by the IPCC, sort of. The realm of the IPCC report is climate change, meaning that species loss (mass extinction) is considered in a separate silo. To limit global warming to 1.5 degrees centigrade requires radically reducing carbon emissions as well as actively de-carbonizing the atmosphere. The popular conception of a Green New Deal is to 1) increase carbon emissions to build low emission technologies while 2) gradually phasing out existing technologies.

A typical way of calculating the impact of green production is to reduce estimated emissions from existing technologies as more efficient green technologies replace them. But the old and new technologies both exist in broadly integrated webs of economic production. By analogy, an electric car may (or may not) produce fewer greenhouse gas emissions than a gasoline powered car, but this tells us little about the environmental impact of manufacturing cars more generally.

What of the infrastructure— factories, roads, transmission lines, industrial inputs, etc. that must be built and maintained to produce them? And what of the inputs that must be mined, transported, processed, transported (again), processed (again) and transported (again) to production facilities? This research paper by economist Jan Kregel provides a description of the distribution of capitalist production. The environmental impact of ‘green’ products is the totality of what went into their production, not end-use calculations.

Regarding the manufacture of solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles, not only should the environmental costs be calculated as carbon emissions, but also in terms of the arable land, breathable air and drinkable water consumed. And what of the natural systems destroyed? These have bearing when habitat loss is considered. Habitat loss is also both a product of industrial agriculture and it impacts the future viability of all agriculture. These in turn are aspects of natural systems, interrelated webs of life that people disrupt at our own peril. This is a central finding of research into mass extinction.

A Green New Deal conceived as tampering around the edges of industrial capitalism— employing the un- and under-employed to manufacture solar panels and batteries for electric vehicles, would add to carbon emissions and other environmental harms at a point in history when the collective ‘we’ can’t afford it. However, when considered more broadly as a social and environmental program operating under a strict carbon budget, it is the best chance for making the transition to a sustainable and just future.

The carbon budget should both be taken to heart and broadened to include a concept of sustainability beyond just the climate. Within the carbon budget laid out by the IPCC, there is no way to implement the conception of a GND (Green New Deal) as existing political economy with green manufacturing added to it. In fact, there is no conception of a GND other than as funding a radical transition away from almost everything that defines current economic production. And the alternative isn’t business as usual— environmental decline will force the issues.

Given the central role of agriculture in both climate change and species loss, land reform is needed to decentralize, rescale and localize agricultural production. This has historically been among the most contentious issues between capitalist and socialist visions of political economy. Powerful corporations currently own or control vast swaths of agricultural land. A GND could compensate large tract owners for their land and the proceeds be taxed to assure that democratic political control is maintained.

Second, agribusiness should be removed from anything related to agriculture in favor of regenerative farming methods. Animal agriculture should be nationalized, with humane conditions mandated and the price of animal products made to reflect their true production costs, including environmental costs. Local and regional agricultural cooperatives should be created as autonomous and democratic collectives, with legal mandates to grow and distribute nutritious food to everyone in the region while minimizing the environmental footprint.

Local and regional agricultural collectives could serve as models for green production of non-agricultural goods. Using comprehensive environmental accounting methods that have been around since the 1970s, all environmental costs related to producing and distributing goods should be mandated to 1) minimize environmental production costs while 2) prioritizing the production of necessities (housing, clothing). Inclusive employment would be used to produce and distribute necessities according to need.

Prototypes for this system already exist across the U.S. Amish communities use organic and regenerative farming methods, minimally participate in consumer culture, avoid energy intensive technologies, support specialized production within their communities and grow what makes sense for their respective regions and growing seasons. They also partake of modern medicine and dentistry, participate in the cash economy and trade goods and services locally and regionally.

There is no agrarian romance at work here. In the poor rural areas where I meet the Amish, they are conspicuously healthier than the non-Amish, have established community support systems and seemingly functioning lives, relationships and economies. This, despite having little to none of the consumer accoutrement considered essential in the wider culture. Life is hard everywhere, but the essential nature claimed for capitalist culture— of consumption, acquisition and individual self-realization, seems improbable given this focus on community. Left largely unconsidered regarding ending capitalism is that there really might be better ways of doing things.

Despite the deep instantiation of agrarianism in the American imagination, most Americans don’t / won’t see reversion to primitive agrarian collectives as viable. And such a vision is utopian without taking apart the large, complex and deeply integrated relations of Western political economy. And even if these were addressed, the rest of the world shows little indication of abandoning capitalism.

If the world could be sectioned off and environmental decline with it, these would be good counter arguments. However, that China has been reinvented with a heaping helping of green technology has done little to slow global environmental decline. Russia is a petrostate with a long history of human-inflicted agricultural calamities. Like the rest of us, the Russians will need a functioning climate and the species-abundance that makes agriculture possible.

The proposals deemed realistic— green tinkering around the edges, won’t solve the environmental problems the world faces. And the reason that potential solutions are so complicated is that social complexity has been built into modern political economy. Addressing the parts means addressing the whole— witness the systemic carbon footprint that green production is indissociable from. The problem isn’t aspects of capitalist modernity, it is the whole of it.

The attractiveness of pre-modern political economy is that there is several thousand years of accumulated knowledge to support it. Homes built before the existence of mechanical systems were situated to capture sun and shade and could be opened to allow air flow in summer and closed to restrict it in winter. They were built using materials and methods that allowed single rooms or areas of houses to be heated with degrading the broader integrity of the buildings.

Traditional agricultural methods likewise descended as accumulated knowledge to ‘passively’ control insect damage, use the entire growing season to maximize fresh food production and produce crops that last through the winter. Monoculture production is an industrial package that includes genetically modified seeds and chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides. Agribusiness and regenerative agriculture are fundamentally incompatible.

Industrial agriculture has historically replaced traditional farming methods by externalizing costs. In economic terms, industrial food costs less to grow than through traditional farming. However, regenerative agriculture has low environmental costs while industrial agriculture has high environmental costs. Through this mismatch between economic and environmental costs, what is efficient by capitalist logic is suicidal by environmental logic. The environmental reckoning that is upon us tells the true story.

The idea of commensurability is crucial here. A forest felled to build a shopping center represents the loss of a functioning ecosystem. A price or tax charged for doing so, e.g. a carbon tax, doesn’t replace the forest in environmental terms. Money is to a forest as a horse is to a rocking chair. Outside of capitalist theology, the concept is nonsensical. And neither God nor the forest set the price or received the payment. Even in capitalist terms the market price is contextual— it depends on factors like scarcity to which the forest bears no relation.

As it regards land redistribution, the Amish way of spreading their communities isn’t scalable because of land costs. They go where arable land is cheap. Any large-scale redistribution of land as part of a Green New Deal could only work if land costs are near zero. Borrowing money to buy agricultural land immediately imparts the logic and relations of capitalism. The lender would own the land until the debt is repaid, giving it say over how the land is used. The same would be true for agrarian collectives globally.

In the most basic sense, capitalism must be gotten out of the way for a GND to produce environmentally sustainable political economy. Gresham’s Law implies that solar panel producers can undercut their competition by externalizing their costs (polluting). This leaves the firms that can most effectively pollute as the survivors of market competition. Regenerative agriculture can’t compete with industrial agriculture because the competition is rigged.

The proposition laid out here isn’t that the whole of Western political economy be shifted to primitive agrarian production. It is to suggest that there exists accumulated knowledge about how to get by in the world that preceded capitalist modernity. The ‘end of history,’ the broad and deep replacement of the knowledge, methods, relationships and logic that preceded modern capitalism, leaves few places to turn as it is proved unworkable.

The first battle to be fought toward environmental and social justice is political. The politicians who used a Green New Deal as a talking point, as well as the few who actually thought about it, can’t win the political battle without a broad political movement backing them. However, such a movement would be foolish to muster the political strength and then hand it over to stewards of the existing order.

The 2020 presidential election seems the time and place to raise the political stakes. Given the improbability of resolving environmental problems within capitalism, and that Bernie Sanders is the only national political figure to take a stand, however qualified, against capitalism, his candidacy can serve as a rallying point. Unless radical action is taken quickly, events will unfold that pose a risk to large numbers of people. Once Mr. Sanders has been pushed out of the way by establishment Democrats, and he will be, events can take on a life of their own. Crisis by default or with a purpose, the choice is yours.