In January 1918, President Woodrow Wilson presented his 14-Points to Congress, a statement of principles that became the basis for a negotiated settlement that ended World War I, including the break-up of the defeated Ottoman Empire. The speech was also meant to provide a framework for preserving world peace — an idealistic sentiment later given false teeth by the establishment of the League of Nations in 1920. Point 12 says that “the other nationalities [including Kurds] which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development….” But this didn’t happen: the Turks, under Kemal Ataturk, balked at Kurdish sovereignty, and war-victorious Britain laughed at the homeland promised to the Kurds.

Today, the Kurdish diaspora is mostly spread out over four regions in the Middle East — Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. They have been, at best, a tolerated presence, almost in a constant state of battle in their pursuit of a permanent homeland. They have been used and abused for decades by the Brits and Americans — British Petroleum discovered lots of oil in the Kirkuk region in the 1920s, making the Kurdish-held province subject to seizure by Iraqis ever since. The Americans have let them down repeatedly since President Wilson’s pronouncement, including Herr Doktor Kissinger’s realpolitik double-cross of the Kurds in 1975, after they’d gone up against the Ba’athist regime at America’s behest. “Covert action should not be confused with missionary work,” said the Nobel Peace laureate.

The Kurds have been around since the time of Saladin, Muslims and Jews pushing back against Crusaders in a holy war of the Abrahamics, one Semite beating the snot out of another, that stretches back in time to happy Ozymandias (see Hubris). The family jewels were purloined from the Holy Land long ago by Europeans (Turin, Glastonbury, Paris) and there’d be no reason for Euros to have trashed the cradle of civilization again, had it not been for a new hole-y war — the discovery of oil, with all its cachet. And here we are today. George W. Bush, an oil man, called the hellish activity in the modern Middle East a “crusade…against Terrorism,” but you get the feeling his terror is all about control of the region’s oil.

Meanwhile, the Kurds are still looking for a Kurdistan that they can call Home; still in-fighting — these days against ISIS, in a poignant and seemingly hopeless narrative of constant survival. Turmoil in the region has resulted in massive displacement and a global refugee crisis. As the late Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani asks out loud near the end of his life, “Have the Kurdish people committed such crimes that every nation in the world should be against them?” But no one seems to be listening.

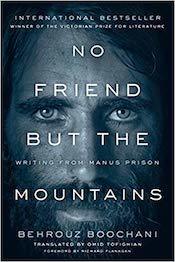

Probably the most controversial narrative about one Kurd’s plight and consequent flight to freedom and stability is Behrouz Boochani’s asylum-seeking odyssey No Friend But the Mountains. In it, the 36 year old from Ilam, a Kurdish city in the mountainous northwest of Iran, details his narrow escape from Iranian religious authorities looking to arrest him for the ‘subversive’ journalism of Werya, a Kurdish cultural magazine he edits. He flees toward Australia, seeking asylum, where he hopes to find a stable life in a culture that ostensibly protects freedom, especially the fundamental freedom of expression.

Early in his award-winning memoir, Boochani wonders whether instead of heading toward Australia for personal freedom he should instead have fled to the mountains to be with his brothers-in-arms defending his people. He decides that there are different ways of being a resistance-fighter and that his weapon of choice is the pen rather than a gun. “To this very day,” he writes, “I don’t know if I have a peace-loving spirit or if I was just frightened…maybe my cowardice … redirected my thoughts to privileging the power of the pen, compelled me to pursue cultural expression as resistance.”

The problem is that for years refugees and asylum-seekers would make their way to Indonesia and then seek out traffickers who would help sneak them into Australia by boat, where they hoped to find protection from the life-threatening abuses they left behind. Unfortunately, these ‘boat people’ were often delivered in shabby vessels that sometimes fell apart at the seams, resulting in horrific deaths at sea.

In addition, from a bureaucratic point of view, these asylum-seekers were thought of a “queue-jumpers,” forcing their situation on Australian authorities busy processing the migration requests of  people ‘standing in line.’ Neither the queue-jumping nor the drownings were considered acceptable, and after much political hand-wringing, the conservative Australia government came up with a poorly-named “Final Solution”: No More Asylum Boats.

people ‘standing in line.’ Neither the queue-jumping nor the drownings were considered acceptable, and after much political hand-wringing, the conservative Australia government came up with a poorly-named “Final Solution”: No More Asylum Boats.

Behrouz Boochani arrived in Australian waters from Indonesia just a few days after a new law went into effect that permanently excluded anyone seeking asylum who had arrived by boat. One problem solved, a new one opened: what to do with asylum-seekers who had arrived after the law went into effect on October 31, 2013?

Now without the desire to return to their countries of origin and without hope of settling in Australia, the seekers were sent to detention centers in Nauru (families) and to Manus (single males), an island off the coast of Papua New Guinea. There is no plan beyond that. Boochani, and hundreds of others, have been languishing on these islands, waiting to be processed as refugees and for third countries to offer asylum. Boochani has been waiting six years.

No Friend But the Mountains details the harrowing experience of leaps of desperation and the tyranny of time, observes the processes of unwarranted confinement keenly, explores the catastrophe of dumping a first world migration policy into a third world colony’s lap. The risks asylum-seekers take are extraordinary. Boochani, a poet as well as a journalist, describes the terror of the boat ride from Indonesia to Australia:

The ruckus of our terrified group

The sound of weeping in the background

The beating of waves

The petrified, silent screaming

The tormented wailing

Waves rocking a cradle containing a corpse

Hour after hour of adrenaline waves and the fear of imminent drowning.

Boochani observes his environs with a certain poetical style; he’s tuned in to the sensual and the sensory. Stuck in the Manus Island detention center, pacing, without hope, under a sun so hot it feels like he’s being “cremated.” Multi-cultural refugees crossing paths in their pacings; united facilely by their common plight, but ultimately divided by language, religion, and tribe; assigned numbers to make it easier for the staff to avoid remembering their names. Boochani nicknames everyone he sees: The Blue Eyed Boy, The Toothless Fool, The Young Guy With A Ponytail, The Irascible Iranian, The Cadaver, Maysam The Whore, The Gentle Giant, etc. Afghan, Sri Lankan, Sudanese, Lebanese, Iranian, Somali, Pakistani, Rohingya, Iraqi, Kurdish.

Even the generator has a nickname — The Oldman Generator — and seems to be possessed by a malignant spirit, “a living being, with a soul, an organism that takes pleasure in throwing the prison into disarray whenever it feels like it.” The most meagre comfort depends on its operation — the water pump for flushing toilets. When it fails, and it does regularly, the consequences are immediate. “Within a few minutes,” he writes, “the toilets cease to function and the smell of shit and piss sweeps, the whole space from end-to-end.” The stench grows, the floor floods. The heat saps and drives them toward insanity.

Being on Manus Island means dealing with the locals, who provide much of the low-level maintenance and serve as guards. They don’t want the asylum-seekers in their community. They are resentful at having no say in details worked out by PNG and Australian citizens miles and miles away. “The imprisoned refugees feel that they are in a nightmare; their feelings about the locals are transformed into a nightmare,” Boochani thinks. Colonized, the locals have an odd presence, tribal instincts married to a rustic Australian humor gone feral, almost phantasmagorical.

According to Human Rights Watch,“[G]roups of local young men, often intoxicated and sometimes armed with sticks, rocks, knives, or screwdrivers, have frequently assaulted and robbed refugees and asylum seekers on Manus Island.

Details of riot and closing.” The tension mounted until a group of about 80 locals broke into the refugee compound and attacked the detainees on February 17, 2014 and Reza Barati, The Gentle Giant, was murdered by locals.

No Friend But the Mountains is in a sense a conjuring up of the evil of banality, the extraordinary dreariness of inescapable routine, of progress into some future not marked by time but by mythopoesis, a mental journey that, as you pace in the sun, or lay back looking up from your bunk in the night, dissolves your connectedness not to reality but the presumptions you once lived by, every moment of uncertainty a brand new paradigm. Doing laundry, flip-flopping through slip-slop, lining up for chow, observing the inward-looking others pacing, orbiting the yard.

As he watches his fellows drift toward depression, self-harm and suicidal ideation, Boochani muses, “These forced conditions of loneliness make everyone endure scenes of an internal odyssey that would ruin any man. The odyssey summons dark angels and secrets relegated to the unconscious; like a magical curse it positions before every prisoner’s eyes the most long-standing issues and bad blood tied up in the soul.” Hopelessness married to time begets torture.

Eventually, after being told by authorities over and over that they will never be allowed into Australia, the Papua New Guinea supreme court declares the detention center “illegal” and it is closed down on October 31, 2017. Detainees must now leave the compound. More tension erupts, as feeling unsafe in the community, some asylum-seekers refuse to leave, leading to violence during forced removals to ne, semi-open encampments elsewhere on Manus, run by Paladin, a controversial contractor, providing essential services and security to the asylum-seekers.

No Friend But the Mountains represents a new kind of intersection of social apps, poetry, academic analysis, philosophy, as well as memoir. It has been celebrated as a new form of crucial journalism — WhatsApp messages developed into a book of observations in detention. This novelty seems to have sparked enthusiasm for championing the book that followed. Boochani has won a series of Australia’s richest literary prizes for his memoirs and has been hailed as “one of Australia’s finest writers,” despite not being allowed to enter Australia. A separate documentary, using the same mobile phone, has been released. An animated glimpse into his adventure is available.

But perhaps the wildest development out of the memoir (and other accounts) is a play titled Manus written by Iranian writer Nazanin Sahamizadeh. It premiered in, of all places, Tehran. Iranian theatre-goers were treated to a play showing “the inhumane conditions and human rights violations in the Manus camp.”

John Donne once wrote that no man is an island, but what did he know? His bells were always tolling over something. Ask Boochani — he sees himself as “an island in an archipelago,” most days entire unto himself. It must seem strange, for a man coming from a stateless culture, to be left stateless by another culture trying to make a statement; taking up his pen not against the enemies of Kurdistan but of freedom.