Lot’s Wife is a poem by Anna Akhmatova, a poem I only regard as prophetic in retrospect. Reading this poem again has not just been a trip down Memory Lane, but also a venture into the wilderness of history. Akhmatova was born in June, 1889 and died in 1966, and her social circle included many of the Russian poets of her generation, including some who were crushed by the Stalin regime and others who endured to live out their long lives. Falling in love with a poet is not so distant from falling in love with a lover. Only time turns the romance into a marriage, and certain poems become such close travel companions that they even show signs of aging, with lines and traces much like our faces when they become period pieces. Since I do not know Russian, all I can do is compare English translations of my favorite Russian poets. Sometimes I listen closely to Russian poems being read through websites, just to hear the music.

Akhmatova has been in my personal pantheon since I first read her work, just around the time I first I met my husband in 1975. Both events illuminate each other in memory. I was 20 then and he was 32. The storm and stress of the 1960s had subsided, but that storm had washed away some public lies and some common ground was bearing fruit. The Stonewall Rebellion of 1969 had not been the beginning of queer resistance, but it was a clear sign that queers also belonged to a rebel generation. At least in the big cities, and increasingly even in the small towns, you no longer had to be rarely brave or lucky to live outside the closet.

Between 1969 and 1981, there was a kind of Golden Decade for many lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. For many others, however, the fractures of a class divided society still ran through their own lives. Racism, likewise, was not going to die a natural death. In the legal realm and even in daily life, racism was being pruned like a bonsai tree, but the roots also leapt out of the pots, struck new ground, went sideways, and sprouted up again with camouflage foliage. Being transsexual or “obviously” queer remained a big risk, including the kind of death penalties that the big media either ignored, reduced to a paragraph, or treated with lurid fascination.

My guy and I are white and now solidly middle-class. As for the presentation of self in everyday life—and a tip of the hat here to the sociologist Erving Goffman—we can pass as straight but are not enchanted by this kind of performance art. In 1975 we still had great hopes that this country might go from change to change, and in the general direction of sanity and solidarity. And plenty of changes came, but the public climate included some truly ugly weather on the horizon. The church crusaders were becoming a true political power by the end of the decade, and by 1981 Reagan was in the White House.

In the same year, The New York Times published an article titled “Rare Cancer Seen In 41 Homosexuals.” Dr. James Curran, a spokesman for the Federal Centers for Disease Control, was quoted: “The best evidence against contagion is that no cases have been reported to date outside the homosexual community or in women.” By 1982, the mysterious disease was called gay-related immune deficiency. The epidemiology only became clearer over time, while the public story grew both more complex and menacing. If the control of an epidemic is like old school firefighting, then some public figures concluded that you fight the fire from the outside and let the center burn. If queers burned, well, life goes on and who needs them? If whores and junkies also burned, then some of the faithful grew convinced that the wrath of God had come like a guided missile.

Making the right kind of trouble in the wrong kind of company was an ambition of my early youth, and now that I’m losing my hair and teeth the conviction grows in me that my time on earth was not wasted. The torch passes to the young of course, that is a natural law. Now that my years are on the count down, I find more time to read again the works I love best: the shape-shifting gods and mortals of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, for example, and the family drama of Kafka’s Metamorphosis, in which the protagonist sheds the larval human body and becomes an overgrown insect. I also listen to the music I love best: Lady Day because you’ve got to love her, or most anything by Mozart. I make discoveries, too: the pianist Vincent Larderet, for example, playing Brahms and Berg like no one else. I get lost in African art and stories because they become a home away from home. Once again I spend days and nights reading poems and even writing them again.

If anyone is tempted to tell me that is a life of luxury, pardon me for quoting Big Bill Haywood of the Wobblies when the press corps sniped at him for smoking expensive cigars: “Nothing’s too good for the working class.” Right, I’m not Bill Haywood, but that’s not really my point. I’m convinced that we, the people, have to raise at least the ground floor of social democracy for all workers. That would be a better social and material bargain for the middle class as well. As for real democratic socialism, let’s go! Though that also means democracy from the ground up. If we don’t get democracy right, we will get socialism wrong.

In my study here in Los Angeles, four framed linocut prints by Natalia Moroz are on a southern wall I face when working at my desk, near three arched windows facing east. Each print is a portrait of a poet: the Russian poets Anna Akhmatova and Marina Tsevetaeva, the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke; and the Greek poet Constantin Cavafy, who lived in the Greek community of Alexandria, Egypt. (According to the Encyclopedia Brittanica, “Cavafy generally spoke English; even his Greek had a British accent.”) A book of Cavafy’s poems was new to me when I found it in the home of one of my teachers long ago, and a few days later we began an affair. I have a hunch he left it in plain sight because he had a hunch that teenager was gay. Though Rilke may be my favorite among these four poets, each of them is dear to me. I have learned lessons from them all, though more through their perspectives than their styles. Moroz has also made linocut print portraits of other poets, including W. H. Auden, Robert Frost, and Osip Mandelstam. Here is the portrait of Akhmatova by Moroz, which can be found at the Etsy website.

Since I am slowly writing a book of memories, I can only bow before the great writer Nadezhda Mandelstam (1889 – 1980) who had a truly phenomenal memory, one of her weapons against the regime of Stalin. Her two books of memory, Hope Against Hope (1970) and Hope Abandoned (1974) were first published in the West, translated by Max Hayward. She noted that her husband, the poet Osip Mandelstam (1891 – 1938), spoke these words: “Only in Russia is poetry respected, it gets people killed. Is there anywhere else where poetry is so common a motive for murder?”

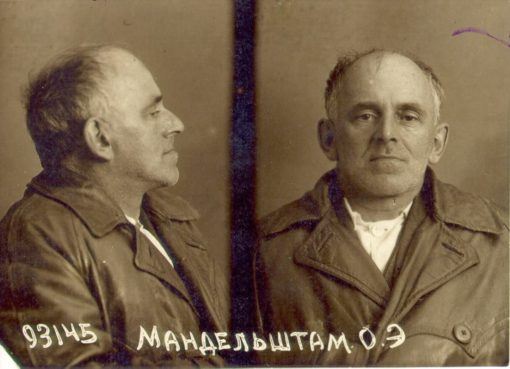

He had dared to read one of his poems, known as the “Stalin Epigram,” at a few small private parties. The poem is a portrait with a “cockroach mustache.” But friends sometimes became spies, and the poem came to the attention of Genrikh Yagoda as soon as he became the NKVD boss. As Nadezhda Mandelstam wrote years later, “Yagoda liked M.’s poem so much that he even learned it by heart – he recited it to Bukharin – but he would not have hesitated to destroy the whole of literature, past, present and future, if he had thought it to his advantage. For people of this extraordinary type, human blood is like water.” She committed all of her husband’s poems to memory for safekeeping, and worked later to have them published. After Osip Mandelstam was arrested again in 1938, he was sentenced to five years in a labor camp, but died the same year in a transit camp near Vladvostok. Here is the 1938 NKVD mug shot of Mandelstam:

No, I don’t dare compare the years under Stalin to the years under Reagan, Bush Senior, Clinton, and Bush Junior. Nor were the members of ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) ever facing state show trials, or being shot in basements or on the edge of trenches. The cops pitched us into their vans, they baited us as queers, whore and junkies, and sure, sometimes they roughed us up because why not? Yes, distinctions must be made. Just as there are distinctions among zoological specimens, so there are degrees of organized lying and malign neglect during the rule of our own political monsters, both those who have been mummified in official memory and those who are still so life-like among the living. The police spies who dropped by ACT UP meetings in Philly were rank amateurs compared to Stalin’s bloodhounds, and our spells in jail could be scary but were never truly hard time.

Even so, the AIDS epidemic is in every sense in my bloodstream, though the virus is no longer a death sentence for those who can get decent drugs. The dead do not haunt my every thought, but I count them among my kindred spirits and will never betray them. Time passes and does not heal all wounds, and besides I can’t bear so much happy talk from the helping professions. What can I say about Obama? Plenty, in fact, though for some other time. What can I say about Trump? He nearly writes the daily script of TV comedians. Too many hipsters would rather laugh at Trump than fight the Republicans and Democrats who keep each other in the truly big business of war and empire. From the far right many of us always knew what to expect, but we had to learn much tougher lessons from “progressives” who can’t find their spines with a flashlight. They also labored mightily, if unwittingly, to put Trump and his crew in power. They give us the endless civics lesson that every vote counts, and then lose their shit when we don’t vote for them.

So many of my friends and comrades in the AIDS activist movement died years ago when the medical drugs were often rough and sometimes intolerable. People with AIDS sometimes made maps of available toilets so they could go outside without making a scene. Then the drugs got better and lengthened lives, including my own, but we are aging and making exits in the course of time. I have very few personal photos of those fierce, tender and vanished comrades, since cell phones came along only with the “second generation” of ACT UP. But their faces linger in my mind’s eye, and even some of their voices linger in my mind’s ear. Of course, some of their faces and voices remain in some public photos and film documentaries.

Kiyoshi Kuromiya, who lived two blocks west of our former house on Lombard Street in Philly, was surely my closest comrade in ACT UP, and I shared many late night coffees with him while a haze of maryjane surrounded him like a halo. He was not a plaster saint and he could be damn difficult, but he counts among the best human beings I’ve met in my life. He was born in a Japanese concentration camp—he refused to say internment camp—on Heart Mountain in Wyoming in 1943, and died in 2000 in Philly. Here is a photo of Kiyoshi, a name that means bright, shining, clear:

Finally, here is the poem by Akhmatova, in the English translation I like best by Stanley Kunitz and Max Hayward. I won’t belabor what this poem has meant for me in the past, nor why I dare to regard these words as a key to the secret chamber of my own life, which is at the same time an open secret. I’ll just say that these lines lead me back to my native Sodom, they call me to look back; and I choose to turn even if I turn into a pillar of salt. Whether this concerns you in my case is your own concern. For myself, this poem is not an appeal for sympathy. Solidarity is something else altogether, and when we remember the dead we are calling them into communion with the living:

And the just man trailed God’s shining agent,

over a black mountain, in his giant track,

while a restless voice kept harrying his woman:

“It’s not too late, you can still look back

at the red towers of your native Sodom,

the square where once you sang, the spinning-shed,

at the empty windows set in the tall house

where sons and daughters blessed your marriage-bed.”

A single glance: a sudden dart of pain

stitching her eyes before she made a sound . . .

Her body flaked into transparent salt,

and her swift legs rooted to the ground.

Who will grieve for this woman? Does she not seem

too insignificant for our concern?

Yet in my heart I never will deny her,

who suffered death because she chose to turn.