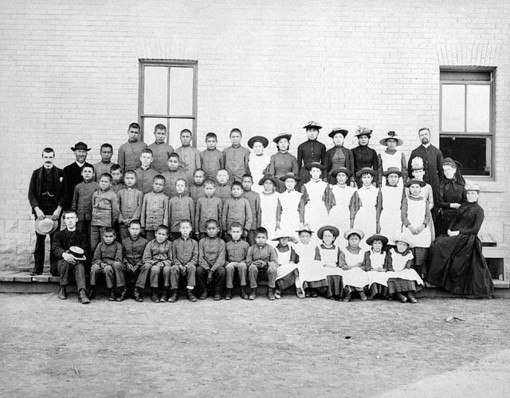

Photograph Source: St. Paul’s Indian Industrial School, Middlechurch, Manitoba, 1901 – Public Domain

Over the years I have written a number of scholarly historical articles on Indigenous education of both children and adults. Recently I have been reviewing some of the current scholarly writing on how Canadians might understand more profoundly why their government and churches treated First Nation’s peoples with such utter disregard for their education and well-being. Canadians, it seems to me, now know that “bad things” happened to Native children and youth in residential schools from around 1879 until the mid-1980s. But the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (active between 2008-2015) and the publications of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Affairs (2015-) have released stories and studies that have “unsettled the settler within” (Paulette Regan, Unsettling the settler within: Indian residential schools, truth telling, and reconciliation in Canada [2010]).

These stories of abuse have crawled out of dark dungeons. Many of us can scarcely comprehend why a teacher might smack a child across the mouth with a ruler for “speaking Indian” (one of thousands of cruel acts perpetrated on Native children). They were stripped of their clothing and given a number upon entering the residential school. They were separated from their siblings by gender and removed from parental contact and community bonds. They were fed lousy food in lousy buildings. Around 6000 children died of various diseases, particularly tuberculosis. Their own spiritual traditions and practices were attacked mercilessly. Spiritual desolation awaited them down the road.

Still, some might assume that these acts of violence were the work of “bad apples.” They were mere blots on the “good intentions” of government and churches. And that Canada, unlike its violent neighbour to the south, was basically benign and had good intentions to help native people to solve problems such as disease, hunger, loss of traditional economy and their unceded land. This judgment cannot be sustained.

In fact, in a critical discussion of James Datschuk’s bomb-shell book, Clearing the plains: disease, politics of starvation, and the loss of indigenous life (2nd ed., 2019), Mary-Ellen Kelm says that Canadians will learn that their government used “starvation” to force Indigenous people off the land. She states forcefully that “Clearing the plains will help Canadians set what they are learning about the residential schools within a history of settler colonialism and systemic violence” (p. 201). What Canadians might not see, Kelm opines, is the “normative violence that lies at the heart of Canadian settler colonialism” (ibid.). An excruciating example of systemic normative violence is that shortly after the crushing of the Riel Rebellion of 1885, the “residential school staff ushered the children of the Battleford Industrial School into the courtyard to witness the hanging of the men convicted of murder” (p. 202). “Reading Clearing the plains,” Kelm avers, “makes it hard to deny that Canada has been built on a foundation of violence, exploitation, and genocide” (p. 203).

How can Canadians be taught the dark side of their history? Susan Neylan thinks that: “James Datschuk’s Clearing the plain is a fitting choice for unsettling national narratives about the peaceful resettlement of the western prairies, for confronting presumptions about the benevolence of Canadian policy towards Indigenous peoples or a fair treaty process, and for appreciating how this dark side of Canadian history resonates today” (p. 218). And resonate it does in the immense suffering and traumas of those victims of coercive assimilation into a society that wouldn’t permit them to be equal partners.

Julian Brave NoiseCat says that: “We the First Peoples of this land have Armageddon in our bones and utopia in our souls. Generations of trauma are imprinted on our chromosomes, linking our DNA to the sorrow of our ancestors” (“Armageddon in our bones, utopia in or souls: the contemporary Indigenous renaissance,” in the Canadian Geographic Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada [2018]), p. 7)

John Milloy’s A national crime: The Canadian government and the residential school system, 1879 to 1986 (1999) takes us away from sunny meadows into the dark world of residential schools. Here, I want to focus on Milloy’s chapter as a starting point to discover the animating vision of these schools. Both government and churches shared the “civilizing logic” of the Imperial Indian policy heritage. This logic is an inherently violent intervention into the lives of Indigenous peoples. It is anchored in deeply racist assumptions about the nature of Native people. One cannot treat anyone as an object to be moulded, manipulated and beaten into the desired shape without carrying considerable hatred or self-righteousness in one’s outlook and sensibility.

By the late 19th century the Canadian Department of Indian affairs had concluded fatefully that something more drastic than the day school had to be instituted for the education of Indigenous children. But there was an “even more profound impediment in the day-school equation”—the “Indian ‘race’ itself.” Nicholas Flood Davin, lawyer, journalist and Regina-based politician, authored an influential report in 1879, “Report on industrial schools for Indians and Half-breeds,” noting that “the influence of the wigwam was stronger than the influence of the school” (p. 24). He believed you had to control Indian youth when they were “very young. The children must be kept constantly within the circle of civilized conditions.”

Indeed, the Department perceived that the native children’s traditional activities—such as making sugar, gathering various fruits and curing of corn—made it exceedingly difficult to “keep the Indian Children in subordination. They are so much accustomed to move about and sail and have things their own way at home, that after all it is really wonderful that any of them know anything at all.” The children had to be separated from parents and community if they were to assimilate “true knowledge” and become fully human. This violent act, while rupturing what Christians usually think of as a divine institution, was deemed the only hope to kill the Indian and save the man. We need to pause for a moment. This is cultural genocide.

Milloy makes it clear that: “Officials and missionaries, even if they operated in remote corners of the land, did not stand outside Canadian society. They shared with other Canadians a discourse about Aboriginal people that informed their activities and, in this case, their educational plans. The basic construct of this discourse, with due regard to the poetic and philosophic utility of the ‘noble savage’, continued to be that of the uncomplimentary comparison between the ‘savage’ and the ‘civilized’” (p. 25). “Enlightened” Canadians would have “to elevate the Indian from his condition of savagery” and from their “present state of ignorance, superstition and helplessness.” Once out of the cocoon, they could metamorphose into “useful members of society.” They would be “intelligent, self-supporting” citizens” (cited, p. 25).

In The inconvenient Indian: a curious account of native people in North America (2012), award-winning Indigenous novelist Thomas King states: “Certainly the sentiment for the extinguishment of the Legal Indian has been around for a while. “I want to get rid of the Indian problem,” said Duncan Campbell Scott, head of Canada’s Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932. “Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department …” (p. 72). This is a now a rather infamous quote.

The Department’s Inspector of Schools for the North-West, J. A. Macrae thought that adult Indians were “physically, mentally and morally …unfitted to bear such a complete metamorphosis.” Davin even suggested they might make some progress, and “be taught to do a little at farming and at stock raising and to dress in a more civilized fashion, but that is all” (cited, p. 26). The Reverend E.F. Wilson, the founder of the Shingwauk Residential School, considered adults “the old unimprovable people.” The adult Indians were hindrances to their children’s learning. Davin pointed to the “influence of the wigwam,…superstition, [and] helplessness”; thus the child who attended day school also “learned little and what little he learned soon forgot while his tastes [were] formed at home, and his inherent aversion to toil [was] in no way combatted. By attending the day school, they remained as depraved as their parents. Aboriginal children raised in their own families, Lawrence Vankoughnet, a Department of Indian Affairs official in the late 19th century, ascertained, unlike white families, taught “little that is beneficial” or practicable in a modern world (p. 26).

With land-hungry white settlers pouring into the plains in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, officials believed they needed to act quickly. The “red man” would vanish or die off unless “special measures” were adopted “to force a change in his [the Indian’s] condition” (p. 27). The churches agreed. It was only the young that could redeem the doomed adult native society. Milloy says that the Mennonites, for instance, followed this script. “The Indian is the weak child in the family of our nation and for this reason presents the most earnest appeal for Christian sympathy and co-operation; … we are convinced that the only hope of successfully discharging the obligation to our Indian brethren is through the medium of the children, therefore educational work must be given the foremost place” (p. 28).

The founding idealized vision of the residential school wanted the school to serve as a surrogate home. But life would be the big teacher, the primary enabler of the metamorphosis of the “new man.” Milloy captures the vision beautifully. “Children on coming to the school would enter the White world in an act of transformation symbolized by the shearing of Aboriginal locks and the donning of European clothes and boots.” This was the foundational transition from savage to civilized.

“Thereafter, they would live the life of White children within a round of days, weeks, months, and years punctuated by the rituals of European culture. The week began with the Sabbath, and the passage of the seasons was marked by the festivals of church and state: Christmas, Easter, the innumerable saints’ days, Victoria Day, Hallowe’en, and so forth. These rhythms would be imprinted on the child through appropriate celebration: presents, concerts, music with bright tunes and improving sentiments” (p. 36).

In every aspect of their daily lives, the residential school sought to replace the Indigenous “symbolic order”—the contexts within which objects and actions take on meaning. Thus, the children and youth were radically disoriented and reoriented to a place filled with European “meaning.” The government and churches knew that “task of overturning one ontology in favour of another was the challenge they faced is seen in their identification of language as the critical factor” (p. 38). Since language carries the culture’s DNA, its ontological heritage, the civilizers had to try to eradicate “speaking Indian.”

That was the crucial link connecting children to their cultural past: a rich symbolic system of resources to live well in their own places. And they punished any child caught speaking his or her own language. This is nothing less than a pedagogy of assault. In the end, the “’circle of civilization” did not live up to its name. “It did not because it could not. Government and church correspondence and reports reveal that there was, as an inherent element of the vision, ‘savagery’ in the mechanics of civilizing the children” (p. 41).

For Milloy, nobody emerged within the strained culture of violence in the residential schools to protect and care for the children. They were not protected, nourished, clothed properly, safely housed and educated. “Right from the beginning, as the Davin Report was implemented in the early 1880s, the Department and its church partners created a persistently dark and shameful reality to which were consigned thousands of Aboriginal children” (p. 47).

In conclusion, Canadians (and all humanity if we consider the global mistreatment of Indigenous people) must find ways of facing the dark side of our history. We cannot wish it would just go away. Indigenous people are here to stay. They won’t disappear. Their legacy of suffering and trauma requires that the Canadian government and its people ask itself what it will take to enable Native people to flourish.