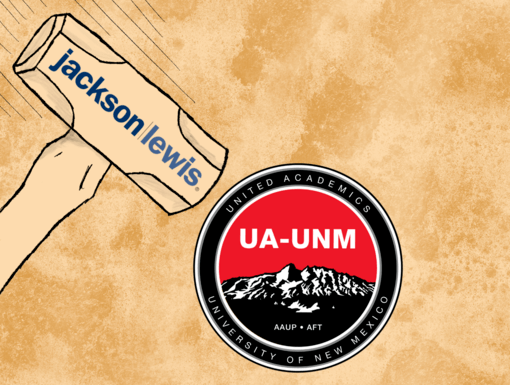

Drawing by Nathaniel St. Clair

From 2008 to 2018, few professors at the University of New Mexico—whether tenured, or tenure-track, or adjunct—received wage increases greater than the cost of living. In most of those years, wages remained stagnant, while out-of-pocket costs for health insurance and retirement contributions increased. As a result, some professors, particularly those faculty who teach on semester-to-semester or short-term contracts, make less today than they did ten years ago. Median salaries for UNM faculty, already low at all ranks and dramatically low in comparison to similar universities, continue to shrink.

Last week, after years of on-campus organizing, UNM faculty—United Academics of the University of New Mexico—filed with the local labor board to form a faculty union. Nearly 1,000 faculty signed union authorization cards. If we win the election, the more than 1,700 faculty at UNM collectively bargain with UNM over wages and working conditions.

As any educator working in higher education knows, faculty working conditions are student learning conditions. The worse that things have gotten for faculty at UNM, the worse they’ve gotten for students. A decade of steep cuts to the academic mission at UNM has created a crisis in UNM’s ability to hire and retain faculty, educate students, conduct research, and serve the state of New Mexico as the flagship institution of higher learning. These cuts have convinced many faculty that UNM leadership isn’t serious about its mission. Endless austerity has shrunk the university. Year after year, UNM balances its books on the backs of faculty, staff and students. According to UNM’s interim provost in a February 13 email to all faculty, declining state support and an even sharper decline in enrollments over the past five years have cratered UNM’s budget. Revenue at UNM’s main campus “is now about $24 million less than it was in 2009.”

And last week faculty learned once again that fiscal austerity at UNM, like at most institutions of higher education, only applies to faculty and staff salaries and the university’s academic mission. In response to the faculty union effort, the University of New Mexico hired the notorious union-busting law firm Jackson Lewis. According to Steven Greenhouse of the New York Times, Jackson Lewis “is widely known as one of the most aggressively anti-union law firms in the U.S.” It was founded in 1958 and today employs more than 900 attorneys in 58 offices in 37 states, with offices also in Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C.

In the ten years since UNM gave its faculty even a cost-of-living raise, revenues at Jackson Lewis have more than doubled, from $196 million in 2008 to $420 million in 2018. In other words, as real wages have declined for workers in higher education, particularly for faculty at UNM, revenues at the company that invented what it calls “union avoidance” have skyrocketed.

The university has not said what it will pay Jackson Lewis. But when the University of New Hampshire hired Jackson Lewis last year to oppose faculty union organizing there, the university, a public institution similar to UNM, paid the firm nearly a quarter of a million dollars.

Jackson Lewis is not just any law firm. It is management’s go-to firm for anti-union campaigns. They’ve represented thousands of employers, including large retailers such as Ikea, manufacturers such as IBM and Boeing, and health care firms from coast to coast. In the past decade, it has moved aggressively into public-sector higher education anti-unionism. In recent years, in addition to UNH and now UNM, it has represented Barnard College, Emerson College, Northeastern University, Middlesex County College, Columbia University, Goucher College, and NYU among others. College administrators hire Jackson Lewis for the same reasons for-profit employers do: to bargain to impasse with existing unions, and, in the case of UNM, to stop unions from being formed in the first place.

Jackson Lewis charges its clients hundreds of thousands of dollars—in some cases millions of dollars—because it’s good at what it does. Its two founders got their start at a firm called Labor Relations Associates of Chicago, Inc. (LRA), which was founded in 1939 by Nathan Shefferman, a man labor historians consider the father of the “union avoidance industry.” Shefferman got his start when Sears and Roebuck hired him to oppose efforts by Sears retail clerks to unionize. Shefferman parlayed that experience into LRA, which had hundreds of clients by the 1940s. According to Professor John Logan, a prominent labor historian, “LRA consultants committed numerous illegal actions, including bribery, coercion of employees and racketeering. Congressional hearings into its activities effectively forced LRA out of business in the late 1950s. But the firm provided a training ground for other union avoidance gurus such as Louis Jackson and Robert Lewis of the law firm Jackson Lewis.”

What do you get when you hire Jackson Lewis? Jackson Lewis doesn’t just advise and consult for its clients. As Logan told a reporter, Jackson Lewis runs the entire anti-union campaign. It “basically runs the entire show,” Logan explained. “They’re writing speeches, training supervisors, making video and websites to convey the anti-union message. They script everything.”

There are thousands of law firms in the U.S. that do management-side labor law, and most do it much cheaper than Jackson Lewis, and most do not bend and break the law as Jackson Lewis has done. When a company or university hires Jackson Lewis, it’s because of its specialty at no-holds-barred anti-unionism. As Professor Logan told me when we talked on the phone, “you don’t hire Jackson Lewis if you want an agreement with a union or you want to respect your employees’ right to unionize. You hire them for their hardball tactics.” You hire Jackson Lewis if you want to delay an NLRB election. You hire Jackson Lewis for their success in “undermining union campaigns.”

Jackson Lewis is in-demand by university administrators because of its reputation, not despite of it. And Jackson Lewis’s reputation is as notorious as its origins. During union organizing at the New York Daily News, Jackson Lewis posted armed guards at factory gates in multiple states to stop union organizing efforts. It directs companies to set up forced overtime when union meetings are scheduled, as it did with Ikea. It threatens workers, as it did in its notorious, and illegal, EnerSys campaign. It intercepts the distribution of union material. It places negative stories about union officials in tabloid newspapers. It operates in a legal gray area, explained Professor Logan, and considers the subsequent legal penalties the cost of doing business. Breaking the law is part of its overall anti-union strategy. Labor busting used to be the domain of Pinkerton goons in jackboots. Now it’s Jackson Lewis lawyers in Brioni suits.

And labor busting today is not just a partisan political activity. Jackson Lewis has emerged in the past few years as a major contributor to Democratic political candidates. During the 2016 election cycle, Jackson Lewis’s political action committee handed out more than $70,000 to federal candidates. More than 60 percent of those donations went to Democrats, including Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY), and Senator and Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris (D-CA).

The University of New Mexico, according to Professor Logan, will most likely deny it’s familiar with Jackson Lewis’s reputation and claim it just needs legal representation. The latter might be true, he said, but the former is most certainly not. “The university will claim this is just a legal process and Jackson Lewis is well regarded, but it’s quite clear that most of the time, when you hire Jackson Lewis, it’s to take a hard line.” And it will be expensive. A basic anti-union campaign, as the one UNM is clearly gearing up to fight, “will cost at least a few hundred thousand dollars. It could be less, but Jackson Lewis isn’t the firm you hire if you have a budget in mind.”

While universities like UNM continue to disinvest in the academic mission, publicly-funded union busting gets a blank check.