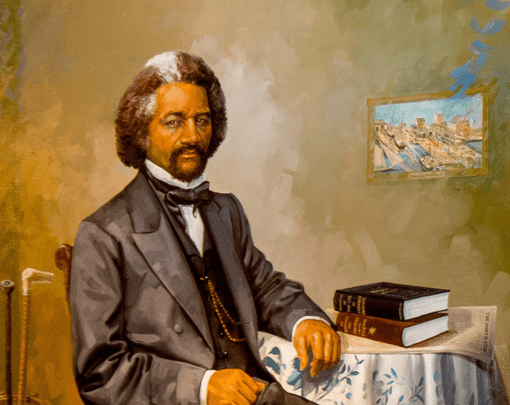

Photo by Maryland GovPics | CC BY 2.0

The global remembering last month of the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the 2018 reboot of the Poor People’s Campaign of 1967-68 suggests that the links between the past and the present are ever evolving and that the past is always present. At this point, it is important to access past demands not achieved, as well as new demands not yet attained, nor arguably made clearly.

In 1857, Frederick Douglass emphasized what have become some of his most quoted words: “If there is no struggle there is no progress.” Continued Douglass, “Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation … want crops without plowing up the ground, they want rain without thunder and lightening. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.”

Douglass admonished the crowd, “This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” As Douglass knew first-hand, “Find out just what a people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted…. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

Douglass was not the last person to make such observations about oppression, struggle, human “progress,” and the necessity to make “a demand.” In his famous 1963 work, originally titled Letter from Birmingham City Jail, Dr. King channeled the legacy and voice of Douglass when he wrote, “freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

We are at another clear and defining moment in human history in which a renewed (and new) set of demands has been put forward, this time meekly based on the first and largely unrealized Poor People’s Campaign from 1967-68.

In May 1967, at the outset of the Poor People’s Campaign, Dr. King said, “I think it is necessary for us to realize that we have moved from the era of civil rights to the era of human rights…. [W]hen we see that there must be a radical redistribution of economic and political power, then we see that for the last twelve years we have been in a reform movement…. That after Selma and the Voting Rights Bill, we moved into a new era, which must be an era of revolution…. In short, we have moved into an era where we are called upon to raise certain basic questions about the whole society.”

With his words, King had transitioned from his focus on African American civil rights to the economic concerns of all Americans. This fundamental shift would include newly linked concerns: “the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism.” In fact, on April 4, 1967, exactly one year before his death, King had made unequivocal his stance on the Vietnam War, as well as his clearly linked program against domestic poverty, military interventions, and deep seated racism, in his politically charged address at Riverside Church in New York City. Noted King, days before that speech, “We are merely marking time in the civil rights movement if we do not take a stand against the war.”

With his new focus on human rights and anti-war activism, King moved into the last movement of his life, the Poor People’s Campaign. (King’s work on his last campaign are best documented in historian Michael Honey’s prescient book, Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign and his important just-released book, To the Promised Land: Martin Luther King and the Fight for Economic Justice. Related first-rate studies such as historian Gordon Mantler’s Power to the Poor, historian Daniel Cobb’s Native Activism in Cold War America, and political theorist David Wilkin’s The Hank Adams Reader, are also worth reading.)

In an important 1967 document titled, “YOU AND THE POOR PEOPLE’S CAMPAIGN,” the Southern Christian Leadership Conference posed the question, “What will we demand?” The response was thus: “We will present to the government a list of definite demands involving jobs, income, and a decent life for all poor people so that they will control their own destiny. This will cost billions of dollars, but the richest nation of all time can afford to spend this money if America is to avoid social disaster.” Elsewhere, the Poor People’s Campaign “demand[ed]”: “Decent Jobs and Income! The Right to a Decent Life!”

There is reason to believe that King’s stance against the war and movement for the poor, as well as the most significant plans to march hundreds of thousands of poor people to Washington to occupy the National Mall, turned the government to panic, ultimately leading to his assassination.

For this new Poor People’s Campaign, the demands include not only better education, meaningful employment, and a true living wage but also clean water, air, food, and additional environmental protections. Indeed, it seems that had King lived beyond 1968, he would likely have been at the forefront of struggles for environmental justice and, like his wife, adopted a vegan diet. Whatever direction he took, however, we can only hope that his life and work would have continued down an ever more radical and revolutionary path.

As was made clear during the press conference on December 4, 2017, in Washington, D.C., to launch the new Poor People’s Campaign, there is still much work to do and still many unrealized demands from 1967-68. Religious leaders of all faiths showed their support. Working people fighting for $15 an hour and strong unions spoke out, as did citizens fighting against a new wave of voter suppression laws and people advocating for clean water, air, and food; for healthcare for all; for housing and against homelessness.

Veterans and others spoke against war, the war economy, and ever-expanding military and warfare and, similar to Dr. King, advocated a “radical love for all humanity.” The crowd gathered that day cheered the courage of a self-proclaimed “red neck” who knows that she has been left behind for a long time. People advocated for “truth and reconciliation.” Most significantly, an Apache leader and activist named Wendsler Nosie pointed toward ecological degradation of land and water, assaults on spiritual, ancestral homelands, and attacks on sovereign Indian nations and Indigenous peoples.

As the organizers of the new Poor People’s Campaign, Rev. Dr. William Barber and Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, wrote last year, “As we’ve traveled the country, it’s become clear that people are ready to come together and demand change. We’ve heard from mothers whose children died because their states refused Medicaid expansion. We’ve met homeless families whose encampments have been attacked by the police and militia groups. We visited the border wall and met with families ripped apart by unjust immigration policies.”

Continued Barber and Theoharis, “Earlier this year, we held a mass meeting in Compton that drew hundreds of people from all walks of life and was simultaneously translated into Spanish, Korean and Armenian. At the end of the meeting, a lifelong welfare rights and anti-poverty organizer, Martha Prescod, approached us with tears in her eyes: ‘I’ve been waiting for this movement for 40 years,’ she said. It’s a sentiment we’ve heard from people all across the country.”

Yet, if we are, as a people, ever to realize the dream of a society that is antiracist, anticolonial, antiwar, and just, and that cares about the environment, as well as honoring treaty rights and Indigenous sovereignty, land, and resources, we must express the inherent power in a demand. And we must discuss and frame our arguments and demands not only around nebulous “immorality” but also, as former student activist and Black Panther Party member Bruce Dixon put it, around “capitalism, socialism, class or working class” and I would add King’s regular references to “materialism,” “radical,” and “revolution.”

I pray Dixon and other critics are not correct, but I do know that taking the “higher ground,” as Barber repeatedly admonishes, will not be enough. Human history has shown time and again that no social justice nor other movement has succeed by doing so alone.