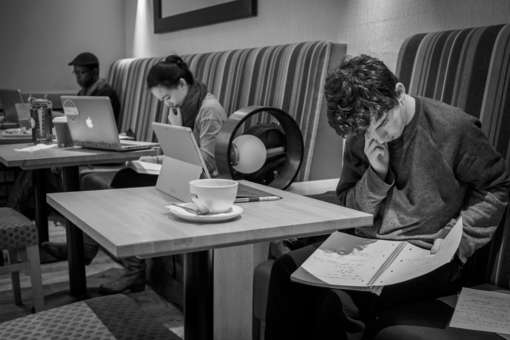

Photo by Per Gosche | CC BY 2.0

University teachers must be courageous pioneers of the new learning age (full of wonder and danger). Our task is to enable our students to acquire the knowledge, skills, sensibility and attitudes to hold their heads high and speak with clear voices in our confusing and anguished world of too much information and too little wisdom. Let me offer a few insights on the specific problems university students must overcome in the information age—if they are to achieve critical consciousness and push against the grain of endless propaganda and fake news.

Our world on speed encourages us to surf, skip lightly, bounce distractedly, and lose concentration. Winnifred Gallagher, in her book, Rapt: attention and the focused life (2009), suggests that we may be experiencing a new moral panic. Professors report that their students are often tired, insanely busy, distracted, and unfocused. “Paying attention”—the mind’s cognitive currency—is a diminishing resource. Sherry Turkle, author of Alone together: why we expect more from technology and less from each other(2011) and expert on robotics and social networking says that we now live in a “culture of distraction.” Paradoxically, the more we connect electronically, the less we converse, and the more we connect the lonelier we are. She thinks that in the “cascade of communication”—some young people send 10,000 text messages a month—we lose our “capacity for solitude, the kind that refreshes and restores. The kind that allows us to reach out to another person.”

Students seem rushed, almost breathless sometimes, as they scamper to complete assignments. The ethos of surfing, inability to live with silence and constant battering by aggressive media (social and other) makes it difficult for students to concentrate and really dig into topics. Far too many students (fortunately not all) make assertions without evidence, accept conventional, media-imposed and politically correct narratives, and have little sense of what it means to sustain an argument. Few have acquired the composition skills of respectful dialogue with other writers. Few seem to want to probe deeply into a subject, to read and think widely, to arrive at the “best argument.” Even fewer pay attention to the proper citation of sources.

Our task as university educators is not just making knowledge resources, packaged in lovely self-directed modules, accessible to men and women. We are inducting them into a “community of practice” (and not providing lovely experiences) that contradicts the frenetic worlds of social and conventional media. University study ought to slow us all down and teach us to concentrate. Students should be nurtured to read widely and slowly, to never settle for any easy answers. We need to build a “culture of critical discourse,” a phrase used by the late maverick sociologist, Alvin Gouldner. The university as a “community of practice” ought to counterpoint the restless monkey mind that is fermented by our distraught information age. We need to figure out how to encourage our students to focus their minds for extended periods of time. This means switching off other inputs; it means being absorbed in disciplined work of discovery and articulation. Italian revolutionary Antonio Gramsci certainly thought that the oppressed Sardinian peasantry had to acquire, through disciplined study, the ability to think abstractly. They had to be able to assess their concrete situations from universal vantage points. If not, they would remain trapped within fatalistic world-views.

In an age of info glut and instant information, university educators must help their students to not only slow down, but also acquire the interpretive frameworks for making sense of the world. In his classic text, The sociological imagination (1959), renegade sociologist C. Wright Mills argued that making sense of the world required that we learn to see our private experiences and personal difficulties as entwined with the structural arrangements of our society and historical times in which we live. It is particularly urgent that all students learn how to think politically—to assess the truth claims of political spokespersons and determine what vested interests are hiding behind their public statements. Students, then, need to learn the skill of discernment, how to assess the authority of the countless sources presented to us as truth. A quick glance at a Wikipedia entry for an essay on Locke’s philosophy just won’t do.

In these grim days the mass media also present us endless lies; our political leaders likewise seldom speak truth to the citizenry. How can some of the leaders of NATO countries get away with withdrawing Russian diplomats without evidence? They must assume that our educational systems do not teach us to think critically. Do they think we can be endlessly duped? They can offer us rubbish and claim something is truthful by merely telling us that it is “highly likely” that Russia was behind the poisoning of the Russian double-agent Sergei Skripal. Recall that the US government lied 935 times to get their miserable way of invading and destroying Iraq in 2003 (Charles Lewis, 935 Lies: the future of truth and the decline of America’s moral integrity[2014]). Lies led to 2.4 million deaths. Lies have consequences, deadly ones.

Ironically, the current dominant intellectual trend in the American academy—post-modern skepticism—plays into the hands of prevaricators like Theresa May and Colin Powell. Neither of these two believe that language has any stable referents. Language is used only in the transitory moment for instrumental purposes that cannot be questioned. In a world where everything is “socially constructed” and where language dissolves material reality and splits signifier from the signified, Powell’s and May’s fleeting views are just one flimsy opinion amongst all others. As Dostoyevsky once said, “One hundred suspicions don’t make proof.” University educators who care about speaking, teaching and living truthfully must affirm that distorted language is parasitical on non-distorted language. Simply, we can continue to argue that our language must account accurately and truthfully for existing states of affairs in the natural and political worlds. False views must be judged accordingly, and their proponents and to account for their lies. Astronomers cannot stand before classes to teach their students that the earth is flat. How is it possible that citizens appear so gullible to false claims about states of affairs in the social and political worlds?

Universities can be islands of clear, rigorous, deep thinking in a glossy sea of information and propaganda. But we will have to teach courageously for this to happen. Thinking against the grain is not in fashion; toeing the patriotic line is. The art of discernment, I believe, is intimately linked to understanding the reasons why we think the way we do and how we justify our actions in the world. In his recent polemical book, Empire of illusion: the end of literacy and the triumph of the spectacle (2009), Chris Hedges stated bluntly, “To train someone to manage an account for Goldman Sachs is to educate him or her in a skill. To train them to debate stoic, existential, theological and humanist ways of grappling with reality is to educate them in values and morals. A culture that does not grasp the interplay between morality and power, which mistakes management techniques for wisdom, not its speed or ability to consume, condemns itself to death” (p. 103).

Antonio Gramsci, the Italian revolutionary who rotted to death in Mussolini’s prison, wrote in the journal Avanti!in 1916 that the educational system ought not “to become incubators of little monsters, aridly trained for a job, with no general ideas, no general culture, no intellectual stimulation, but only an infallible eye and a firm hand.” Gramsci and Hedges underscore the fact that learning must be directed by a strong moral and ethical framework. We must know why we are doing what we are doing. We cannot become, as Richard Hoggart said, “blinkered ponies” (as cited, Hedges, 2009, p. 105).

One British filmmaker, Franny Armstrong, has even suggested that when the future citizens look back at our deranged time they will call it the “Age of Stupid.” What monsters will be displayed in history museums of the future when people enter the special room labelled “How could this have happened”?