In the late 1960s-early 70s, when the Young Patriots organized against Mayor Daley’s efforts to use urban renewal programs in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood, they were fighting new versions of older programs. Slum clearance was not new to Chicago. It had been used to clear the poor from neighborhoods around the Loop in the 1940s and Hyde Park in the 1950s. In the 1960s Urban Renewal programs included building massive public housing high rises like Robert Taylor and Cabrini Greene. Although renewal displacement had impacted poor whites alongside poor blacks, the public housing projects increasingly housed only black families. Poor whites displaced from neighborhoods like Harrison-Halsted and Uptown were pushed into the suburbs, either dissipating or hyper-segregating their communities.

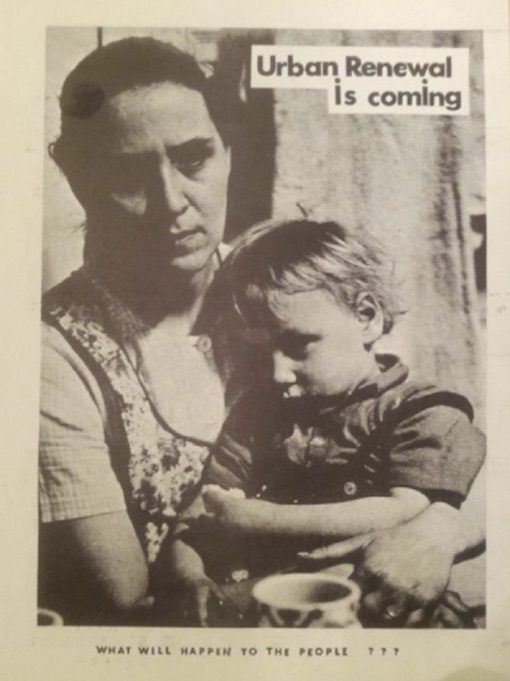

When residents of Uptown were battling unemployment, slum living conditions, absentee landlords, police violence, lack of health care, malnutrition, high infant mortality rates, and disease, the city responded with urban renewal plans. Uptown was slated to be a site for a new community college, and the poor white residents were slated for displacement. A committee of landowners and business owners were selected by Mayor Richard Daley to oversee the process. A coalition of neighborhood leaders, including the Young Patriots, came together to propose an alternative: the Hank Williams Village. This community-envisioned development would include affordable housing, health services, community space, parks and a hotel for displaced southern migrants looking for work. But the city commission pushed through their own development plans and local forces began the displacement process, which included arson by property owners (murdering children and people with disabilities) and increasingly-repressive policing.

The Young Patriots interrupted urban renewal planning meetings and set up community services like health care and welfare application support to meet needs that the city had intentionally neglected. These were the same organizing tactics that were being used in poor black and brown communities across the city. Leaders from those kindred communities, like Bobby Lee of the Illinois Black Panther Party, recognized that being divided along racial lines was preventing people from seeing how the same forces were moving against them with the same tactics. The original Rainbow Coalition between the Black Panthers, Young Lords and Young Patriots was a threat to the controlling interests in the city, including those who were using urban renewal programs to grow rich. And so their attempt to come together across racial lines around class demands was swiftly and violently repressed.

Urban renewal and gentrification are never about meeting the needs of the poor or eradicating poverty. They are plans for stabilizing the economy of the city: maintaining a tax base of middle and upper-income residents and making the city conducive to business interests. While in earlier periods when the economy was expanding, urban renewal was able to include plans for public housing, low-cost community colleges, and other public services. In today’s contracting economy, where homelessness can increase even as the stock market climbs, gentrification consolidates a shrinking middle class in urban centers, pushing the existing residents out of the city or into homelessness. Vacant buildings held for speculation are part of the gentrification process, as the organization Picture the Homeless has well documented.

Gentrification not only impacts the poor in urban areas but is deeply connected to suburban and rural poverty and homelessness. These are the areas where poor people go when they are pushed out of cities. Poverty rates are highest in large urban centers, but most poor people live in suburban and rural areas. And poverty has been growing fastest in those areas. Half of the growth of poverty after 2000 has been in the suburbs, where poverty as grown by 57 percent. These non-metro areas are even less able than large metro areas to meet people’s needs with public transportation and health care clinics.

Gentrification today pushes rents to unprecedented levels, forcing half of all renters in the US—not just those below the poverty line—to pay rents that are unaffordable. (49% of us had unaffordable rents in 2015. Rent is considered affordable if it is less than 30% of your household income.) One in four renters spent more than half their income on housing in 2013. In 2016 rent in Miami consumed 72% of the typical income; in Los Angeles it was 51%; even in Hattiesburg, Mississippi it was 35.8%. Yet only one in four families who are income-eligible for federal housing assistance receive it.

Today we are experiencing a crisis of homelessness tied to the unaffordability of housing in a society where housing is not a right. Even a job does not guarantee that you will have a place to live. This is despite the contradiction that there are far more vacant homes than there are homeless people. One in eight homes in the US are empty, 17.2 million units.

Yet homelessness rose in 2016 for the first time since the Great Recession. This “point in time” count doesn’t include those of us who are living in double-ups, insecure housing, or are moving in and out of homelessness. It only counts who is on the streets on one particular night. School records show that 1.3 million school children were homeless during the 2015-2016 year.

Across the country the poor are living in tent city encampments, including in Uptown where the Young Patriots first learned that being white does not guarantee the right to housing. And across the country tent encampments are facing eviction and harassment. This harassment is part of the gentrification process, pushing people further out and down.

But people who are forced into homelessness have been and continue to fight back. When homelessness first started to take on a more permanent and widespread character in the 1980s, leaders from among the homeless formed the National Union of the Homeless in 20 states across the country.

After ten years of organizing, Picture the Homeless recently succeeded in passing the Housing Not Warehousing Act in New York City. Every year Young Patriot Marc Steiner hosts a remembrance day podcast to name those who died while homeless in Baltimore City. And Chaplains on the Harbor is organizing in rural Grays Harbor County in Washington. Calling themselves the “Freedom Church of the Poor,” they are coming together through survival projects, a School of Hard Knocks and jail ministry. Aaron Scott is their organizer and street chaplain, and he recently became chairman of the Grays Harbor Chapter of the Young Patriots.

Homelessness crosses race, gender and geography, impacting us in cities and in rural areas. And those of us who are not homeless tonight are but one job crisis or health care crises away from it. Those who are homeless tonight are the front lines of a crisis that is expanding. Without the right to housing, none of our housing is secure. The fight against Urban Renewal among the Young Patriots of yesterday inspires us to organize today against the manifestations of dispossession today, and the stakes are even higher.

Colleen Wessel-McCoy is the National Secretary of the Young Patriots Organization.